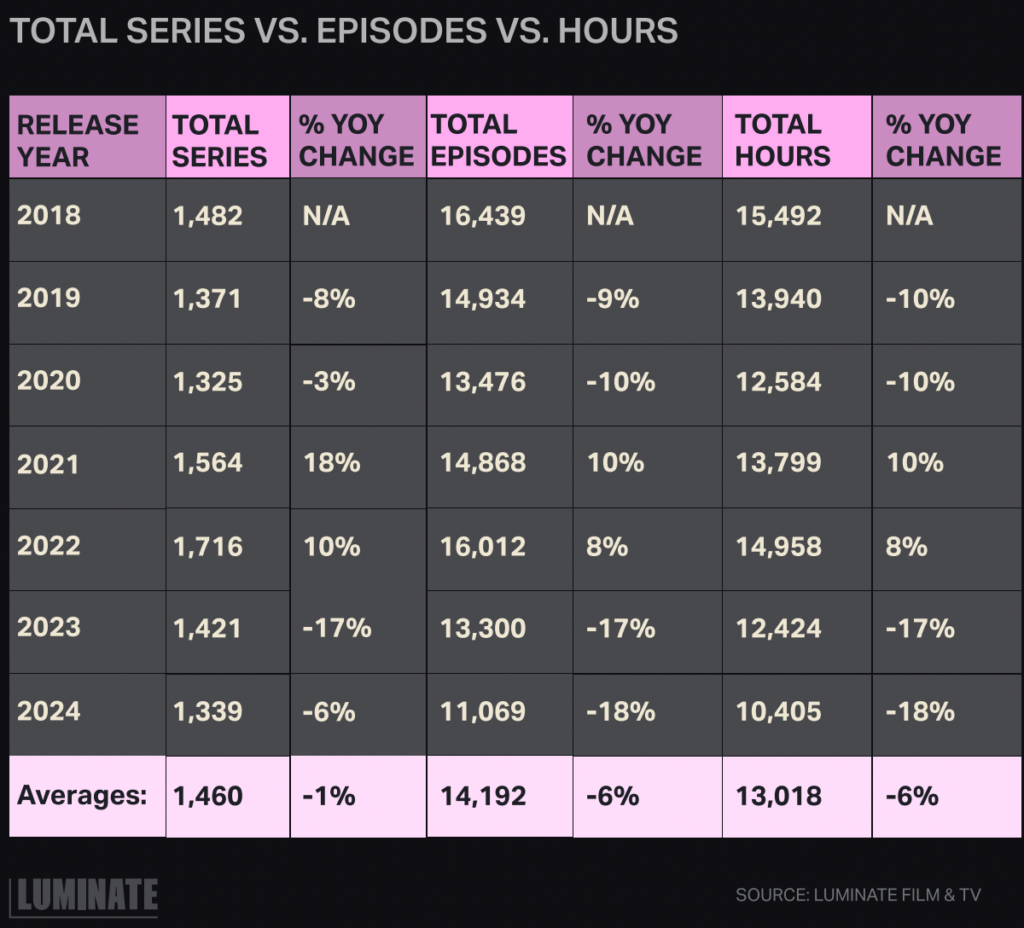

A Luminate report finds the total number of TV episodes produced in 2024 fell by nearly 5,000 compared to just two years earlier as streaming and broadcast networks curb spending.

In a bit of positive news for those following film and TV production trendlines, Netflix executives said on Tuesday that they’re planning to up their annual cash content spend by about $1 billion this year — from $17 billion to $18 billion — as the streaming giant broke records with 19 million quarterly subscriber adds for a total of 302 million global members.

But, increasingly, Netflix is an anomaly in the Hollywood ecosystem, where the divide between the haves and have-nots has been growing since the Peak TV era ended in 2022. And new research finds that, when tallying up all the episodes produced last year, that figure is far lower than it had been just two years ago, before the spending pullback and the dual writers and actors strikes in 2023.

Some 16,012 total episodes of TV content were produced in 2022, a figure that dropped to 13,300 episodes in 2023 and 11,069 last year, according to a new report from data provider Luminate, which is co-owned by Penske Media Corporation, the parent of The Hollywood Reporter. If looking at total hours of TV produced, that figure falls from 14,958 hours in 2022 to 10,405 last year.

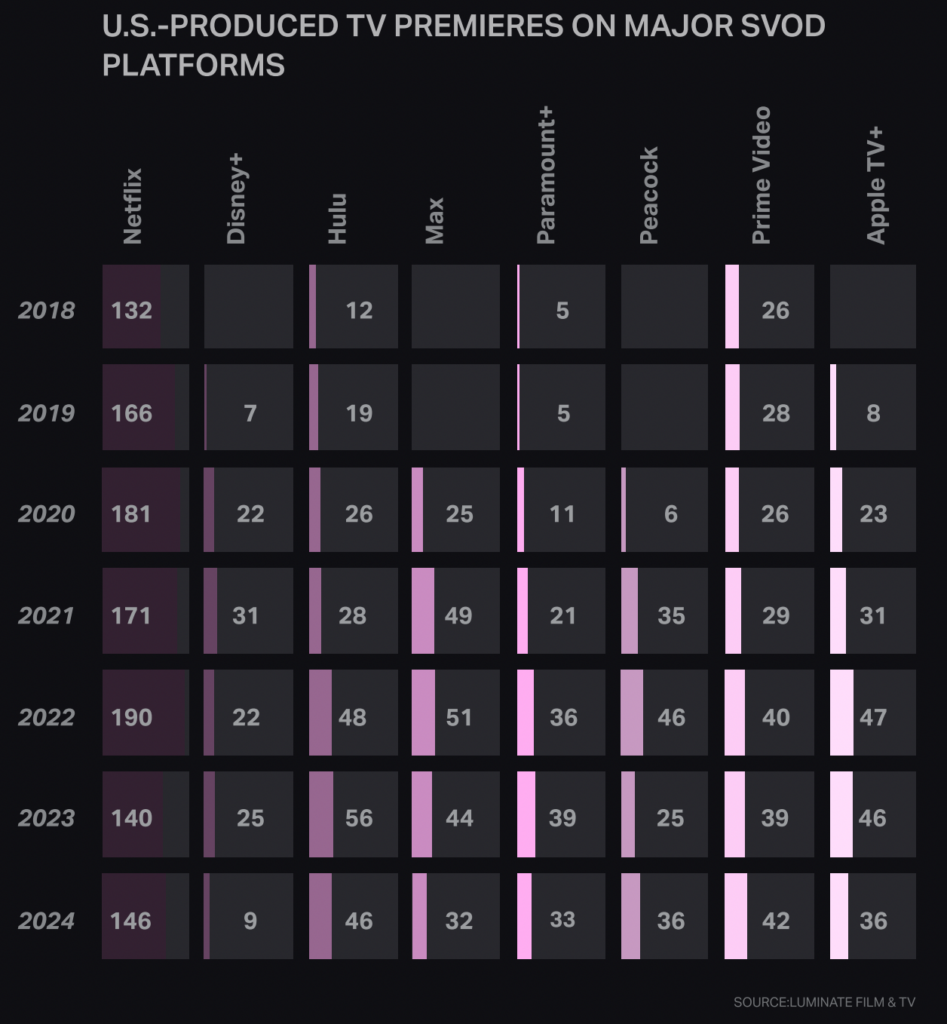

Among streaming platforms, most of those tracked in the Luminate report saw fewer U.S.-produced TV premieres in 2024 than a year earlier. The exceptions were, of course, Netflix, which saw 146 premieres last year compared to 140 in 2023; Peacock, which upped its premieres from 25 to 36 last year; and Prime Video (39 in 2023 to 42 in 2024). Notably, Disney+ — as forecast by CEO Bob Iger — slimmed down its original offerings last year as premieres fell from 25 in 2023 to just nine in ’24 as Disney pushed a larger bundle with Hulu and ESPN+.

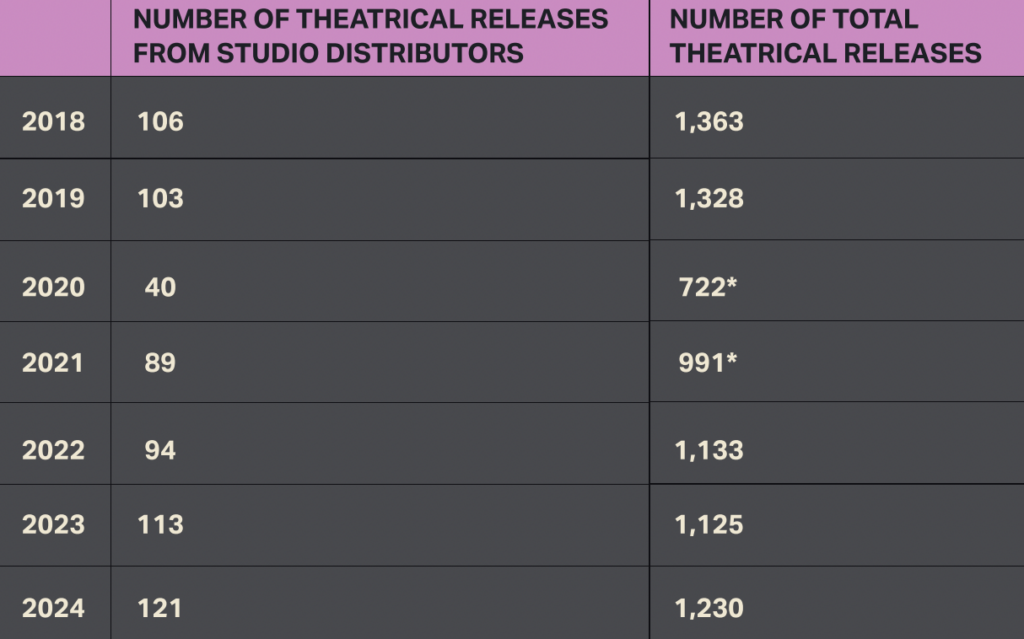

Meanwhile, as studios have pulled back from flooding the zone on streaming releases — in favor of trying to build scale through targeted bundles (like pairing Max with Disney+ and Hulu) — there was a slight uptick in the amount of theatrical product that hit the big screen last year. And that’s despite the 2023 strikes delaying some tentpoles from 2024 to 2025. About 121 releases from major studios were sent to theaters in 2024, an uptick from 113 a year earlier.

While studios sent more features to streaming, the number of streaming-only film debuts fell last year. About 296 movies from major streamers bowed in 2023, last year that figure fell to 264.

The snapshot from Luminate gives a wider lens view from the quarterly updates that permitting office FilmLA has been giving of the Los Angeles County production landscape. Overall shoot days in L.A. — across film, television and commercials — fell from 36,792 in 2022 to 23,480 in 2024. And across the United States, per the latest ProdPro tally in October, production volume dropped 35 percent in the third quarter of last year as compared to 2022.

Courtesy: fern

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure—Capacity”. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ “Table 1: Feature Film Production—Genre/Method of Shooting”. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ “Cinema—Admissions per capita”. Screen Australia. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Table 11: Exhibition—Admissions & Gross Box Office (GBO)”. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ “The Lumière Brothers, Pioneers of Cinema”. History Channel. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ UIS. “UIS Statistics”. data.uis.unesco.org.

- ^ Hudson, Dale. Vampires, Race, and Transnational Hollywoods. Edinburgh University Press, 2017. Website Archived December 22, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kerrigan, Finola (2010). Film Marketing. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 18. ISBN 9780750686839. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Davis, Glyn; Dickinson, Kay; Patti, Lisa; Villarejo, Amy (2015). Film Studies: A Global Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 299. ISBN 9781317623380.

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media. April 29, 1944. p. 68. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ History.com Editors (February 9, 2010). “Thomas Edison patents the Kinetograph”. HISTORY. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ “Why Contemporary Commentators Missed the Point With ‘The Jazz Singer'”. Time.

- ^ Village Voice: 100 Best Films of the 20th century (2001) Archived March 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Filmsite.org; “Sight and Sound Top Ten Poll 2002″. BFI. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2007.

- ^ Rosenstone, Robert A. (1985). Schatz, Thomas; Isenberg, Michael T.; Roffman, Peter; Purdy, Jim; Cavell, Stanley; Alexander, William (eds.). “Genres, History, and Hollywood. A Review Article”. Comparative Studies in Society and History. 27 (2): 367–375. doi:10.1017/S0010417500011427. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 178501.

- ^ “The Kinetoscope”. www.loc.gov. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ Onion, Amanda; Sullivan, Missy; Mullen, Matt; Zapata, Christian (February 9, 2010). “Thomas Edison patents the Kinetograph”. HISTORY. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ Kannapell, Andrea (October 4, 1998). “Getting the Big Picture; The Film Industry Started Here and Left. Now It’s Back, and the State Says the Sequel Is Huge”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ “Market Data”. The Numbers. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ Amith, Dennis (January 1, 2011). “Before Hollywood There Was Fort Lee, N.J.: Early Movie Making in New Jersey (a J!-ENT DVD Review)”. J!-ENT. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

When Hollywood, California, was mostly orange groves, Fort Lee, New Jersey, was a center of American film production.

- ^ Rose, Lisa (April 29, 2012). “100 years ago, Fort Lee was the first town to bask in movie magic”. NJ.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

Back in 1912, when Hollywood had more cattle than cameras, Fort Lee was the center of the cinematic universe. Icons from the silent era like Mary Pickford, Lionel Barrymore and Lillian Gish crossed the Hudson River via ferry to emote on Fort Lee back lots.

- ^ Before Hollywood, There Was Fort Lee Archived July 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Fort Lee Film Commission. Accessed April 16, 2011.

- ^ Koszarski, Richard. Fort Lee: The Film Town, Indiana University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-86196-652-3. Accessed May 27, 2015.

- ^ Studios and Films Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Fort Lee Film Commission. Accessed December 7, 2013.

- ^ Fort Lee Film Commission (2006), Fort Lee Birthplace of the Motion Picture Industry, Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 0-7385-4501-5

- ^ Liebenson, Donald (February 19, 2015). “‘Flickering Empire’ details Chicago’s early dominance of film industry”. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ “Cleveland on Film”. The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Case Western Reserve University. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^

- https://app.crb.gov/document/download/22398

- http://archive.org/download/picturestoriesma03lond/picturestoriesma03lond.pdf

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7e/The_Billboard_1912-02-03-_Vol_24_Iss_5_%28IA_sim_billboard_1912-02-03_24_5%29.pdf

- https://filminflorida.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Analysis-of-the-Florida-Film-and-Entertainment-Industry.pdf

- ^ Abel, Richard (2020). Motor City Movie Culture, 1916–1925. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 136–139. ISBN 978-0253046468.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bishop, Jim. “How movies got moving …”, The Lewiston Journal, November 27, 1979. Accessed February 14, 2012. “Movies were unheard if in Hollywood, even in 1900 The flickering shadows were devised in a place called Fort Le, N.J. It had forests, rocks cliffs for the cliff-hangers and the Hudson River. The movie industry had two problems. The weather was unpredictable, and Thomas Edison sued producers who used his invention. … It was not until 1911 that David Horsley moved his Nestor Co. west.”

- ^ Jacobs, Lewis; Rise of the American film, The; Harcourt Brace, New York, 1930; p. 85

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rasmussen, Cecilia (September 16, 2001). “Movie Industry’s Roots in Garden of Edendale”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Wrong Site, Wrong Year, But Plaque Unveiled On 1st Pic Made in H’wood”. Variety. January 1, 1958. p. 1. Retrieved October 15, 2021 – via Archive.org.

- ^ In the Sultan’s Power at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ Worster, Donald (2008). A Passion for Nature : The Life of John Muir. Oxford: Oxford University Press (OUP). p. 535. ISBN 978-0-19-516682-8. OCLC 191090285.

- ^ Pederson, Charles E. (September 2007). Thomas Edison. ABDO Publishing Company. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-59928-845-1.

- ^ “Hollywood”. HISTORY. August 21, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “How the Spanish flu contributed to the rise of Hollywood”. November 19, 2020.

- ^ How one city avoided the 1918 flu pandemic’s deadly second wave

- ^ Meares, Hadley (April 1, 2020). “Closed Movie Theaters and Infected Stars: How the 1918 Flu Halted Hollywood”. The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “History of the motion picture”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ [1] Archived April 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Will Hays and Motion Picture Censorship”.

- ^ “Thumbnail History of RKO Radio Pictures”. earthlink.net. Archived from the original on September 12, 2005. Retrieved June 19, 2007.

- ^ “The Paramount Theater Monopoly”. Cobbles.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ “Film History of the 1920s”. Filmsite.org. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ “”Father of the Constitution” is born”. This Day in History—3/16/1751. History.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2010. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Maltby, Richard (May 19, 2008). “More Sinned Against than Sinning: The Fabrications of “Pre-Code Cinema””. SensesofCinema.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b [2] Archived June 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Disney Insider”. go.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ [3] Archived May 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aberdeen, J A (September 6, 2005). “Part 1: The Hollywood Slump of 1938”. Hollywood Renegades Archive. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Consent Decree”. Time. November 11, 1940. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Aberdeen, J A (September 6, 2005). “Part 3: The Consent Decree of 1940”. Hollywood Renegades Archive. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ^ “The Hollywood Studios in Federal Court—The Paramount case”. Cobbles.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (August 12, 2007). “Two Outlaws, Blasting Holes in the Screen”. The New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Corliss, Richard (March 29, 2005). “That Old Feeling: When Porno Was Chic”. Time. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 13, 1973). “The Devil In Miss Jones – Film Review”. RogerEbert.com. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 24, 1976). “Alice in Wonderland:An X-Rated Musical Fantasy”. RogerEbert.com. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (January 21, 1973). “Porno chic; ‘Hard-core’ grows fashionable-and very profitable”. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved January 20, 2016.

- ^ “Porno Chic”. www.jahsonic.com.

- ^ Mathijs, Ernest; Mendik, Xavier (2007). The Cult Film Reader. Open University Press. ISBN 978-0335219230.[page needed]

- ^ Bentley, Toni (June 2014). “The Legend of Henry Paris”. Playboy. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Bentley, Toni (June 2014). “The Legend of Henry Paris” (PDF). ToniBentley.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Lardine, Bob (March 18, 1973). “Big Bad Bronson”. The Miami Herald. New York News Service. pp. 1H. Retrieved February 10, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Belton, John (November 10, 2008). American Cinema/American Culture. McGraw-Hill. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-07-338615-7.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (August 24, 2004). “PG-13 remade Hollywood ratings system”. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “How George Lucas pioneered the use of Digital Video in feature films with the Sony HDW F900”. Red Shark News.

- ^ Marsh and Kirkland, pp. 147–154

- ^ “Domestic Movie Theatrical Market Summary 1995 to 2024”. The Numbers. Retrieved December 27, 2024.

Note: in order to provide a fair comparison between movies released in different years, all rankings are based on ticket sales, which are calculated using average ticket prices announced by the MPAA in their annual state of the industry report.

[needs update] - ^ Couch, Aaron; Galuppo, Mia; Kit, Borys (October 21, 2022). “Marvel, DC Among Last Bastion for Supersized Paydays”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (June 19, 2023). “Superhero Fatigue Is Real. The Cure? Make Better Movies Than ‘The Flash'”. Variety. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (March 4, 2024). “Paul Dano Says Superhero Fatigue Is a ‘Welcome Moment’ That Will Hopefully ‘Breathe New Life’ Into Comic Book Movies: ‘Quantity Over Quality’ Is a ‘Big Misstep'”. Variety. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Tyrrell, Caitlin (October 18, 2023). “Why Superhero Movies “Need A Little Bit Of Time Off,” According To Kingsman Director”. ScreenRant. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ “‘Black Widow,’ ‘West Side Story,’ ‘Eternals’ Postpone Release Dates”. Variety. September 23, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ^ Perez, Rodrigo (October 29, 2015). “Exclusive: All-Female ‘Ocean’s Eleven’ In The Works Starring Sandra Bullock, With Gary Ross Directing”. The Playlist.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin P. (October 30, 2015). “Sandra Bullock will lead an all-female Ocean’s Eleven reboot”. Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ D’Alessandro, Anthony (March 16, 2020). “Universal Making ‘Invisible Man’, ‘The Hunt’ & ‘Emma’ Available In Home On Friday As Exhibition Braces For Shutdown; ‘Trolls’ Sequel To Hit Cinemas & VOD Easter Weekend”. Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on March 17, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ D’Alessandro, Anthony (April 14, 2020). “‘Trolls World Tour’: Drive-In Theaters Deliver What They Can During COVID-19 Exhibition Shutdown—Easter Weekend 2020 Box Office”. Deadline. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- ^ “Universal’s ‘Trolls World Tour’ Earns Nearly $100 Million in First 3 Weeks of VOD Rentals”. TheWrap. April 28, 2020. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ Schwartzel, Erich (April 28, 2020). “WSJ News Exclusive | ‘Trolls World Tour’ Breaks Digital Records and Charts a New Path for Hollywood”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on April 28, 2020. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

- ^ “China Shuts Down All Cinemas, Again”. The Hollywood Reporter. March 27, 2020. Archived from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (March 18, 2020). “Trolls World Tour could be a case study for Hollywood’s digital future”. The Verge. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Julia (April 28, 2020). “AMC Theaters will no longer play Universal movies after Trolls World Tour’s on-demand success”. The Verge. Archived from the original on April 29, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ D’Alessandro, Anthony (July 28, 2020). “Universal & AMC Theatres Make Peace, Will Crunch Theatrical Window To 17 Days With Option For PVOD After”. Deadline. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Whitten, Sarah (July 28, 2020). “AMC strikes historic deal with Universal, shortening number of days films need to run in theaters before going digital”. CNBC. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ Rubin, Rebecca; Donnelly, Matt (December 3, 2020). “Warner Bros. to Debut Entire 2021 Film Slate, Including ‘Dune’ and ‘Matrix 4,’ Both on HBO Max and In Theaters”. Variety. Retrieved December 3, 2020.

- ^ Masters, Kim (December 7, 2020). “Christopher Nolan Rips HBO Max as “Worst Streaming Service,” Denounces Warner Bros.’ Plan”. The Hollywood Reporter. The Hollywood Reporter, LLC. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Seitz, Matt Zoller (April 29, 2019). “What’s Next: Avengers, MCU, Game of Thrones, and the Content Endgame”. RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Hannah Avery (January 18, 2023). “US streaming market growth continues, despite changes in the industry”. kantar.com.

- ^ Brew, Simon (October 21, 2019). “Can we stop calling films ‘content’ now?”. Film Stories. Film Stories Ltd. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Taylor, Alex (February 20, 2021). “Are streaming algorithms really damaging film?”. BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

[Martin Scorsese has] warned that cinema is being ‘devalued … demeaned and reduced’ by being thrown under the umbrella term ‘content’.

- ^ Shephard, Alex (July 21, 2021). “Space Jam: A New Legacy Is a Peek Into the Bleak, Cynical Future of Film”. The New Republic. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rivera, Joshua (July 14, 2021). “Despair, pitiful mortals: Space Jam: A New Legacy is the future of entertainment”. Polygon. Vox Media, LLC. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Mendelson, Scott (July 14, 2021). “‘Space Jam: A New Legacy’ Review: A Feature-Length Commercial For HBO Max”. Forbes. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

Quite possibly, as Space Jam: A New Legacy is now a classic example of ‘IP for the sake of IP,’ a brand extension that exists not because audiences want it but because a studio (and/or the film’s star) wants it to continue.

- ^ Kirby, Kristen-Page (July 14, 2021). “‘Space Jam: A New Legacy’—a feature-length ad for Warner Bros.—rises just above mediocrity”. The Washington Post. WP Company LLC. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Tallerico, Brian (November 4, 2021). “Red Notice movie review & film summary (2021)”. RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Evangelista, Chris (November 4, 2021). “Red Notice Review: Dwayne Johnson And Ryan Reynolds Bumble Through Netflix’s Glossy, Lifeless Action Movie”. /Film. Static Media. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Benjamin (November 4, 2021). “Red Notice review—Netflix’s biggest film to date offers little reward”. The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (July 14, 2021). “Space Jam: A New Legacy Never Thought It Could Be a Good Movie”. Vulture. Vox Media, LLC. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

It criticizes shameless, money-grubbing attempts to synergize and update beloved classics … all the while shamelessly synergizing and updating beloved classics. … The studios rarely seem to want to do anything new with their properties other than remind us that they still own them.

- ^ Sollosi, Mary (July 14, 2021). “Space Jam: A New Legacy review: LeBron James enters the server-verse in exhausting reboot”. Entertainment Weekly. Meredith Corporation. Retrieved July 22, 2021.

- ^ Scorsese, Martin. “Il Maestro: Federico Fellini and the lost magic of cinema”. Harper’s Magazine. Vol. March 2021. ISSN 0017-789X. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Taylor, Tom (October 13, 2022). “Martin Scorsese calls cinema’s profit obsession “repulsive””. faroutmagazine.co.uk. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Karr, Mary Kate (November 17, 2022). “Quentin Tarantino says current era is tied for worst in film history”. The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Adekaiyero, Ayomikun (November 17, 2022). “Quentin Tarantino says the current movie era is one of the ‘worst in Hollywood history'”. Insider. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Ntim, Zac (August 14, 2023). “Charlie Kaufman Talks AI, WGA Strike & Slams Hollywood System: “The Only Thing That Makes Money Is Garbage” — Sarajevo”. Deadline. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Schimkowitz, Matt (August 15, 2023). “There’s nothing confusing about Charlie Kaufman’s opinion of Hollywood”. The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ D’Alessandro, Anthony (May 22, 2022). “‘Armageddon Time’ Director James Gray On Why Studios Should Be Able To Lose Money On Art Specialty Divisions – Cannes Studio”. Deadline. Retrieved August 29, 2023.