Although major cinema festivals worldwide have excluded films made by Russian directors this year, Russia is far from absent from movie theaters in the West. Foreign filmmakers have continued to explore the Russian context, incorporating Russian characters and themes into their films. These portrayals range from depictions of villainous figures to brilliant, complex characters. Some of these films have been panned for their stereotypical or negative representations, while others have been celebrated for their nuanced approach to Russian identity and culture.

In these films, Russia is often depicted as a land of stark contrasts, where power dynamics, political tensions, and historical legacies shape the lives of its people. Foreign directors frequently use Russia as a backdrop to explore broader themes such as corruption, moral ambiguity, and the struggle for survival, sometimes offering a critical view of Russian society. In other cases, Russia is portrayed as a mysterious, even romanticized land, full of drama and intrigue.

These films, though not necessarily made by Russian filmmakers, contribute to shaping how the West perceives Russia, often reflecting the complex geopolitical tensions between the two regions. Whether through the lens of thriller, drama, or historical fiction, the Russian context continues to captivate international audiences, sparking discussions on identity, power, and the ongoing influence of Russia on the global stage. Despite the absence of Russian-made films at major festivals, the country remains an important subject of cinematic exploration in the West.

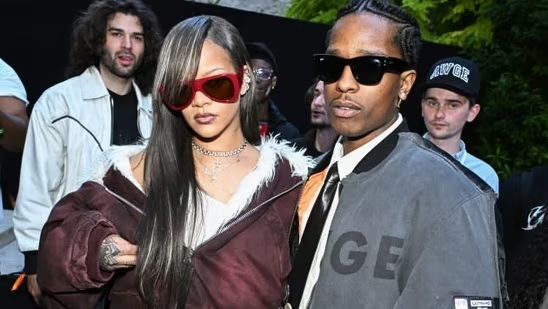

One of the most direct Western films to address Russia and Russians this year is The Palace, a satirical comedy directed by Roman Polanski. Set in the Swiss Alps at the turn of the millennium, the film takes place in a luxurious five-star hotel in Gstaad, a favorite retreat for the rich and powerful, particularly wealthy Russians. The story follows a group of elite characters preparing to ring in the year 2000, including a French marquise with two distinct accessories: a small dog fed black caviar and a pink vibrator tucked discreetly in her handbag.

The cast of characters is eclectic, including actors, porn stars, a 97-year-old Texan billionaire with a much younger wife, and a plastic surgeon catering to elderly clients with grotesque, surgically altered faces. A group of “new Russians” arrives in armored jeeps, accompanied by intoxicated women and stern bodyguards, led by Russian actor Alexander Petrov. These guests are seen hauling heavy suitcases filled with money, symbolizing the newfound wealth of Russia’s elite.

As the characters prepare to welcome the new millennium, the Russians are shown drinking excessively yet managing to remain composed. The scene includes documentary footage of Boris Yeltsin’s final New Year’s Eve address to the nation before stepping down as president. The audience watches Yeltsin announce his successor, Vladimir Putin, and one of the Russian characters in the film raises a toast immediately afterward, hinting that while the “end of the world” might not be here yet, it has only been delayed. This moment, full of dark humor, reflects the complex and often cynical view of Russia’s transition into the 21st century, with its political upheavals and the rise of new wealth and power.

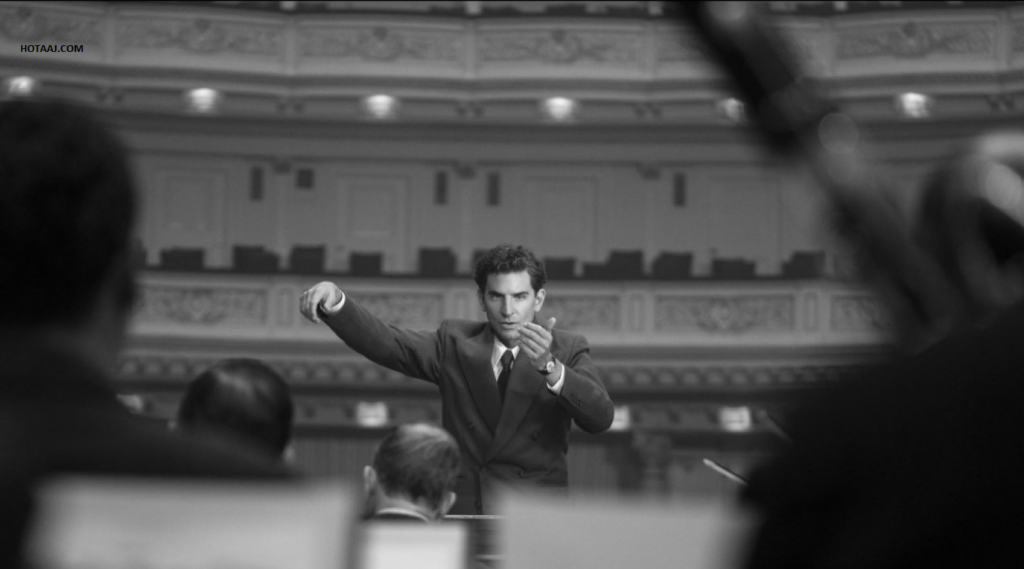

Maestro, a biographical film about the renowned American composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein, intricately weaves together his personal and professional life. The film spans from Bernstein’s impromptu debut as the conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in November 1943 to the emotional struggles during his wife Felicia Montealegre’s illness in the late 1970s. These pivotal moments in his life are framed within the context of an interview with the composer, which bookends the film, offering a reflective lens on his storied career.

One of the key figures in Bernstein’s life and career is Sergei Koussevitzky, a Russian immigrant and esteemed conductor who played a crucial role in shaping Bernstein’s musical development. Koussevitzky, portrayed by Bulgarian actor Yasen Peyankov, was instrumental not only as a teacher but also as a mentor to Bernstein. Born in Ukraine, Bernstein’s roots tie back to Russia, as his mother was from Rovno, Ukraine. Koussevitzky, who had established the first orchestra and music publishing house in the USSR during the New Economic Policy (NEP), is portrayed as a deeply affectionate figure in Bernstein’s life. His bond with Bernstein was strong, and he affectionately called him “Lenochka.” Despite his deep connections to Russia, Koussevitzky’s decision to leave the USSR for Berlin in the 1920s marked the beginning of his enduring relationship with Western music and the arts.

In the film, Koussevitzky is depicted sharing a monologue about Bernstein changing his name to “Burns” to avoid anti-Semitism, though Bernstein declines the suggestion. Koussevitzky was a pivotal figure in helping Bernstein secure his first breakthrough. One of the most iconic scenes of the film recreates the 1943 Tanglewood performance where Bernstein, still an unknown assistant, was suddenly thrust into the spotlight when conductor Bruno Walter fell ill. Faced with an orchestra of brilliant musicians and a critical audience, Bernstein’s performance was a triumph, marking the beginning of his legendary career. As the film shows, this event was a defining moment for Bernstein, with the rest of his career unfolding in the years that followed.

The film highlights the interwoven destinies of Bernstein and Koussevitzky, illustrating the impact of Russian cultural influences on Bernstein’s development and the enduring mentorship that helped shape his path to fame. Through this intricate narrative, Maestro provides a glimpse into the personal and professional forces that propelled one of the greatest musical talents of the 20th century.

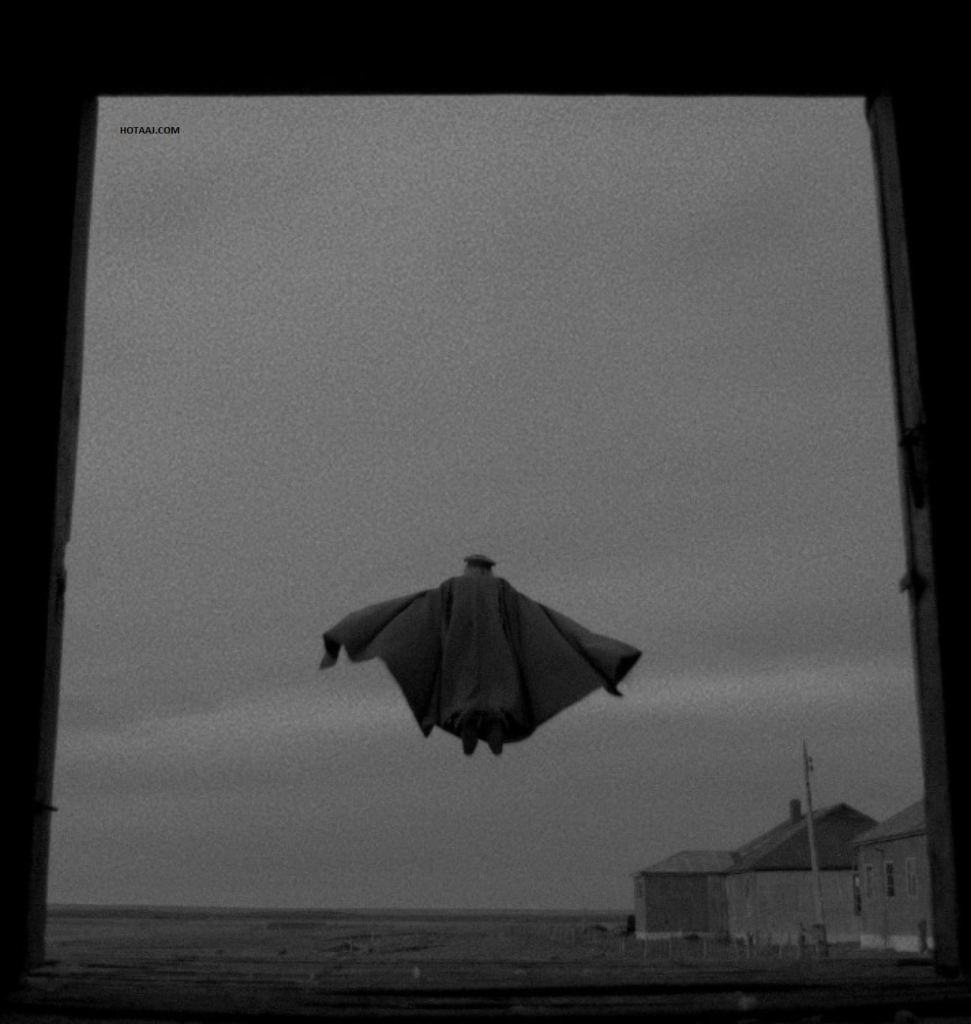

In El Conde, a dark comedy by Pablo Larraín, a Russian character plays a significant role in the bizarre reimagining of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet as an immortal vampire. The film portrays Pinochet’s closest and most loyal ally, Fedor Krasnoff, as a Russian immigrant and former White Army officer who serves as the dictator’s butler. Krasnoff is depicted as a maniacal executioner, dedicating his life to torturing and killing communists, all while dressed in a tailcoat and fur hat. He engages in affairs with Pinochet’s wife and drinks vodka, infusing the film with a twisted sense of dark humor.

In this macabre narrative, Pinochet himself transforms into a sinister black bird that flies over Santiago, seeking victims and calmly extracting hearts from still-living bodies to prepare a cocktail in a blender. This absurd, gothic portrayal of a dictator draws sharp contrasts between the vampire-like ruler and his loyal butler, highlighting their eerie, monstrous relationship.

The film’s plot is an unsettling commentary on power dynamics, dictatorship, and the fate of nations. It resonates with contemporary events, reflecting the ongoing debates surrounding authoritarian regimes, democracy, and the legacy of political leaders. By blending horror, satire, and history, El Conde uses dark comedy to explore the twisted alliances and machinations that often underpin the rule of despots, while questioning the nature of power and its enduring impact on nations and their people.

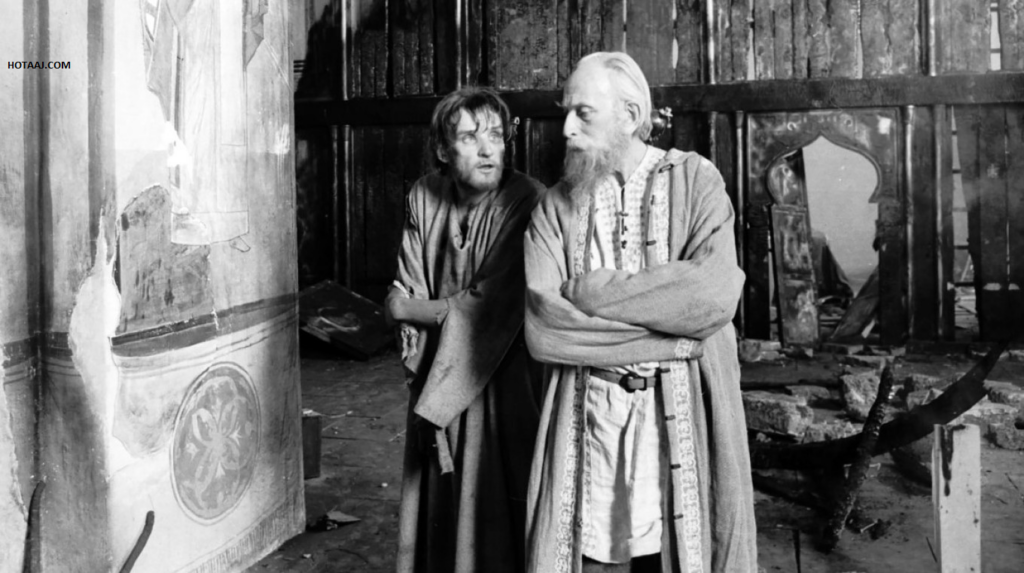

At the Venice Film Festival, one notable Russian film made its presence felt: the original 191-minute version of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev. Featured in the “Venice Classics” program, this 1966 masterpiece, co-written by Tarkovsky and Andrei Konchalovsky, explores the life and work of the iconic Russian painter of Orthodox Christian religious art, Andrei Rublev.

Upon its completion, Andrei Rublev premiered in Moscow in January 1967 and was subsequently screened at the Cannes Film Festival, where it was shown out of competition and awarded the prestigious FIPRESCI Prize by the International Federation of Film Critics. However, despite this acclaim, the film was heavily censored and not widely showcased in the Soviet Union. Only a limited, sanitized version was released in 1971, while Tarkovsky safeguarded the original cut. Over time, the unaltered version of the film was restored with support from the Italian Ministry of Culture, finally screening at the Venice Film Festival years later.

In a poignant twist of irony, Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev now stands as a highly relevant commentary on modern-day Russian reality. The film’s central message echoes a bitter truth: “Humanity has already made all the mistakes and is now simply repeating them.” This theme resonates deeply with contemporary Russian society, offering a striking reflection on the cyclical nature of history and the repetition of past errors. Through its timeless exploration of the human condition and the complexities of history, Andrei Rublev continues to speak volumes about the world, making it a powerful and relevant cinematic work even decades after its creation.

COURTESY: FANDOS ZANOS

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Statistics on the Russian cinema market” (PDF). Nevafilm Research. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ “Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure – Capacity”. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ^ “Film distributors by box office share Russia 2021”. Statista.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Top films by box office in Russia May 2022”. Statista.

- ^ “Annual Report 2012/2013” (PDF). Union Internationale des Cinémas. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Peter Rollberg (2009). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxiii. ISBN 978-0-8108-6072-8.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Peter Rollberg (2016). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 49–52. ISBN 978-1442268425.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j The Encyclopaedia Britannica guide to Russia : the essential guide to the nation, its people, and culture. London: Robinson. 2009. pp. 208–213. ISBN 9781593398507.

- ^ Историческая справка (in Russian). Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- ^ Snider, Eric (23 November 2010). “What’s the Big Deal?: Battleship Potemkin (1925)”. MTV News. MTV. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. “Battleship Potemkin”. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ “Top Films of All-Time”. Filmsite. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ “The 50 Greatest Films of All Time”. British Film Institute. Sight & Sound. September 2012. Archived from the original on August 2, 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ Peter Rollberg (2009). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 172–179. ISBN 978-0-8108-6072-8.

- ^ Peter Rollberg (2016). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 591–593. ISBN 978-1442268425.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Andrei Rublev”. festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ^ “Soviet Film Maker Tarkovsky Dies at 54”. Los Angeles Times. December 29, 1986.

- ^ Stephen Dalton. “Andrei Tarkovsky, Solaris and Stalker”. BFI.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Top 10 most decorated Russian filmmakers”. RBTH. 26 January 2022.

- ^ “The History of Russian Cinema”. Cannes Film Festival. 12 January 2011.

- ^ Nancy Condee (2009). “Aleksei German: Forensics in the Dynastic Capital”. The Imperial Trace – Recent Russian Cinema. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 185–216. ISBN 978-0190451226.

- ^ “‘Deserto Rosso’ Wins Top Prize At 25th Venice Film Festival”. The New York Times. 11 September 1964.

- ^ “Russian film director Konchalovsky wins Special Jury Prize at Venice Film Festival”. TASS.

- ^ Ronald Bergan (21 Jun 2018). “Kira Muratova obituary”. Guardian.

- ^ Birgit Beumers (2005). Pop Culture Russia!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. Abc-Clio. p. 77. ISBN 1-85109-459-8.

- ^ Peter Rollberg (2009). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 157–162. ISBN 978-0-8108-6072-8.

- ^ “Русская кинодвадцатка Радио Свобода “Москва слезам не верит””. Radio Svoboda. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Richard Stites (1992). Russian Popular Culture: Entertainment and Society Since 1900. Cambridge University Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-521-36214-8.

- ^ “26e SELECTION DE LA SEMAINE DE LA CRITIQUE – 1987”. International Critics’ Week.

- ^ “35th International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg, Germany (October 6 – October 11, 1986)”. International Critics’ Week.

- ^ “16th Moscow International Film Festival (1989)”. MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Richard Taylor; Nancy Wood; Julian Graffy; Dina Iordanova (2019). The BFI Companion to Eastern European and Russian Cinema. Bloomsbury. pp. 1923–1927. ISBN 978-1838718497.

- ^ Peter Rollberg (2009). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxxiv. ISBN 978-0-8108-6072-8.

- ^ Birgit Beumers (2005). Pop Culture Russia!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. Abc-Clio. p. 80. ISBN 1-85109-459-8.

- ^ “Berlinale: 1990 Prize Winners”. berlinale.de. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Freeze Die Come to Life”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ “Berlinale: 1992 Programme”. berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ “Review/Film; Harshness of Soviet Life In Lungin’s ‘Taxi Blues'”. The New York Times. 18 January 1991.

- ^ “Cannes Festival”. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: The Wedding”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Tsar”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ “Berlinale: 1990 Prize Winners”. berlinale.de. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ^ “Berlinale: 1991 Prize Winners”. berlinale.de. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: The Assassin of the Tsar”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Anna Karamazoff”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Perekhod tovarishcha Chkalova cherez severnyy polyus”. festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2009.

- ^ Valery Kichin (4 September 2015). “4 Russian films that scooped the Golden Lion at Venice”. RBTH.

- ^ “The 65th Academy Awards (1993) Nominees and Winners”. oscars.org. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ “Berlinale: 1992 Programme”. berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

- ^ “Tchekiste” [The Chekist]. Cannes Film Festival (in French). Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Happy Days”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ Jane Taubman (26 November 2004). Kira Muratova: Kinofile Filmmakers’ Companion. I.B.Tauris, 2004. ISBN 0857714104.

- ^ “Venezia, Libertà Per Gli Autori”. La Repubblica. 31 July 1992. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ “50th Venice Film Festival 1993 – FilmAffinity”. Retrieved 2017-05-28.

- ^ “‘Burnt By the Sun’ Wins Foreign Film Oscar”. Associated Press. March 28, 1995.

- ^ “Hollywood Reporter: Cannes Lineup”. hollywoodreporter. Archived from the original on April 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Assia and the Hen with the Golden Eggs”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 27 August 2009.

- ^ Andrei Plakhov (1994-05-03). “Премьера нового фильма Киры Муратовой”. Kommersant.

- ^ “Российский гуманитарный энциклопедический словарь”.

- ^ “UVLECENJA”. Locarno Festival. Archived from the original on 2017-04-24. Retrieved 2023-05-29.

- ^ “Лауреаты Национальной кинематографической премии “НИКА” за 1994 год”. Nika Award.

- ^ “Призеры 1991-2005 гг”. Kinotavr. Archived from the original on 2013-10-23. Retrieved 2017-04-22.

- ^ Edoardo Pittalis, Roberto Pugliese, Bella di Notte, August 1996.

- ^ Sandra Brennan (2016). “A Moslem”. Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ Peter Rollberg (2009). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-8108-6072-8.

- ^ “The 69th Academy Awards (1997) Nominees and Winners”. oscars.org. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ “Три истории”. VokrugTV.

- ^ “Сеансу отвечают: Три истории”. Seance.

- ^ “Призеры 1991-2005 гг”. Kinotavr.

- ^ Richard Taylor; Nancy Wood; Julian Graffy; Dina Iordanova (2019). The BFI Companion to Eastern European and Russian Cinema. Bloomsbury. p. 1938. ISBN 978-1838718497.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Traveling Companion”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ^ “Berlinale: 1998 Programme”. berlinale.de. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Father and Son”. festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Khrustalyov, My Car!”. Festival de Cannes. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: The Barber of Siberia”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ^ Boris Egorog (25 June 2018). “12 Russian-European movies you must watch before you die”. RBTH.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Moloch”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Taurus”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f “100 главных русских фильмов: 1992—2013”. Afisha.

- ^ “Svetlana Baskova in the TV program Cult of Cinema”. Cult of Cinema.

- ^ “В Петербурге суд запретил фильм “Зеленый слоник””. Meduza.

- ^ “27th Moscow International Film Festival (2005)”. MIFF. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ “”А помните, вы вчера товарища генерала за погон укусили?”: 23 факта о “ДМБ””. Kinoreporter.

- ^ “Winners 1991–2005”. Kinotavr. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-01-25.

- ^ “Poisons or the World History of Poisoning / Jady ili Vsěmirnaja istorija otravlěnij”. KVIFF.

- ^ “Яды, или Всемирная история отравлений”. VokrugTV.

- ^ “Яды, или Всемирная история отравлений. Х/ф”. Russia-1. Archived from the original on 2020-11-20. Retrieved 2023-05-28.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “24th Moscow International Film Festival (2002)”. MIFF. Archived from the original on 28 March 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Dan Fainaru (3 December 2003). “The Last Train (Poslednyi Poezd)”. Screen Daily.

- ^ Deborah Young (September 9, 2005). “Review: ‘Garpastum'”. Variety. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ “Russian film wins award in Venice”. RBTH. 2008-08-07.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Russian Ark”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- ^ “Italianetz”, Berlinale Film Archive, 14 February 2005, retrieved 17 July 2017

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: 977”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 14 December 2009.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Tale in the Darkness”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ “Ugly Swans”. Tretyakov Gallery.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: The Banishment”. festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- ^ “Official Awards at the 64th Venice Film Festival”. www.labiennale.org. Archived from the original on 2008-04-17. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ^ “80th Academy Awards Nominations Announced” (Press release). Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 2008-01-22. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

- ^ Fabien Lemercier (2008-05-25). “Cantet wins Palme d’Or and Sorrentino, Garrone and Dardenne brothers scoop awards”. Cineuropa.

- ^ “2008 Sundance Film Festival Award Winners”. SlashFilm. 2008.

- ^ “Final Press Release (July 11th, 2009)” (PDF). Karlovy Vary International Film Festival.

- ^ “Федеральный закон от 05.05.2014 г. № 101-ФЗ”. Kremlin.

- ^ “НЕ В МАТЕ ДЕЛО: ЗАКОН О ЗАПРЕТЕ НЕЦЕНЗУРНОЙ ЛЕКСИКИ РЕГЛАМЕНТИРУЕТ… РАБОТУ ПО ПРОКАТНОМУ УДОСТОВЕРЕНИЮ” [Does not have to do with curse words: Law concerning ban of curse words regulates… work concerning the screening certificate]. Cinemaplex. 7 May 2014.

- ^ “Постановление Правительства РФ от 17.11.1994 N 1264 (ред. от 10.03.2009) “Об утверждении Правил по киновидеообслуживанию населения””. Legal Acts.

- ^ “Berlinale. Archive. Prize winners 2010”.

- ^ “La Biennale di Venezia – Official Awards of the 67th Venice Film Festival”. Labiennale.org. Retrieved 2013-09-12.

- ^ Scott Roxborough (22 January 2010). “‘Jolly Fellows’ to open Berlin Panorama”. The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Andrei Plakhov (12 February 2010). “Веселая разлука”. Kommersant (in Russian).

- ^ “Cannes Reveals International Critics’ Week Lineup; ‘Ain’t Them Bodies Saints’ Makes the Cut”. Indiewire. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ “Official Awards” (PDF). Festival del Film Locarno. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- ^ “TIFF Adds More High-Profile Titles, Including Jonah Hill’s ‘Mid90s,’ ‘Boy Erased,’ ‘Hold the Dark,’ and Many More”. IndieWire. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Official Selection”. Cannes. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ Leffler, Rebecca (21 May 2011). “Un Certain Regard Announces Top Prizes (Cannes 2011)”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (2011-09-10). “‘Faust’ wins Golden Lion at Venice”. Variety. Retrieved 2011-09-10.

- ^ Dave McNary (24 September 2015). “Venice Winner ‘Francofonia’ Bought by Music Box for U.S.” Variety.

- ^ “Venezia 69”. labiennale. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ “Кинобизнес / Cамые прибыльные и убыточные отечественные фильмы в кинопрокате России 2013 года” (in Russian). Кинобизнес. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ “Zakupki.ru. О механизмах господдержки кинематографии” (in Russian). Искусство кино. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- ^ Михаил Филберт (2015-03-26). “Количество успешных российских фильмов выросло”. Cinemaplex.

- ^ “Close-Up on “Hard to Be a God” and the Medieval in European Cinema”. MUBI. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ^ “Chagall-Malevich”. BIFF. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ “Awards 2014 : Competition”. Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ 72ND ANNUAL GOLDEN GLOBE® AWARDS NOMINEES ANNOUNCED. dickclark.com. Retrieved 11 December 2014

- ^ “Zvyagintsev’s ‘Leviathan’ Picks Up 6 Awards at Russian Film Ceremony”. Moscow Times. 4 February 2015.

- ^ Harvey, Dennis (20 June 2016). “Film Review: ‘Under the Sun'”. Variety. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Kohn, Eric. “Under the Sun Review: Documentary Goes Inside North Korea”. IndieWire. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ “‘Under The Sun’ (‘V lutsah solntsa’): Film Review”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ Gray, Carmen (2 December 2015). “Russian film exposes the workings of North Korea’s propaganda machine”. The Guardian. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ “Under the Sun”. The New Yorker. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ “Prizes of the International Jury”. Berlinale. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ “Archiv. Prize winners 2018”. Berlinale.

- ^ “2016 Karlovy Vary IFF Awards Winners: ‘It’s Not the Time of My Life’ Takes Top Prize”. IndieWire. 9 July 2016.

- ^ Felperin, Leslie (September 15, 2016). “The Duelist (Duelyant): Film Review, TIFF 2016″. The Hollywood Reporter review.

- ^ “Cannes Bullet Points: Brazil the documentary prize and “The Student” the François Chalais Prize”. L’Express. 21 May 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ “The 2018 Official Selection”. Cannes Film Festival. 12 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Debruge, Peter; Keslassy, Elsa (12 April 2018). “Cannes Lineup Includes New Films From Spike Lee, Jean-Luc Godard”. Variety. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Tizard, Will (9 July 2016). “Karlovy Vary Film Festival 2016: Full List of Winners”. Variety. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (28 May 2017). “2017 Cannes Film Festival Award Winners Announced”. Variety. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ “Bafta Film Awards 2018: All the nominees”. BBC News. 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ “Oscars 2018: The list of nominees in full”. BBC News. 23 January 2018. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (14 November 2017). “Andrey Zvyagintsev’s ‘Loveless’ Wins Two European Film Awards”. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- ^ Parant, Paul; Balle, Catherine (2 March 2018). “César 2018 : “120 battements par minute” remporte six prix, dont le meilleur film”. Le Parisien (in French). Archived from the original on 2 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ “Зрители почувствовали “Притяжение”” [The audience felt the Attraction] (in Russian). Kommersant. February 8, 2017.

- ^ “Invasion (2020)”. Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ “International Box Office Surprises of 2018”. The Hollywood Reporter. 21 December 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Barraclough, Leo (3 July 2019). “‘Three Seconds’ Becomes Highest Grossing Russian Film Ever in China (EXCLUSIVE)”. Variety. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Vladimir, Kozlov (November 27, 2017). “Russia Box Office: Disney Film Becomes Top Local-Language Release of All Time”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 30, 2018.

- ^ “БАБУШКА ЛЕГКОГО ПОВЕДЕНИЯ”. Kinobusiness.

- ^ “«Война Анны» Алексея Федорченко: почему новый фильм режиссёра «Овсянок» и «Ангелов революции» — один из лучших в 2018 году”. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ “Картина “Война Анны” получила премию “Золотой орёл” и стала лучшим фильмом года”. Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2022-06-18.

- ^ “«Спутник над Польшей» 2018: кино, музыка и кухня”. www.proficinema.com.

- ^ “Искусство станет ведущей темой 12-го фестиваля российского кино “Спутник над Польшей””. TACC.

- ^ “Тема фестиваля российского кино “Спутник над Польшей” — искусство”. rewizor.ru.

- ^ Когда жизнь подбрасывает. Современное кино глазами молодого мастера

- ^ “Venice to Kick Off Awards Season With New Films From Coen Brothers, Luca Guadagnino and Alfonso Cuaron”. The Hollywood Reporter. 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ “Venice Film Festival Lineup: Heavy on Award Hopefuls, Netflix and Star Power”. Variety. 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ “ЛЕД”. KinoBusiness.

- ^ “Kislota | Acid”. www.berlinale.de. Retrieved 2019-04-17.

- ^ “The 2019 Official Selection”. Cannes. 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ Lodge, Guy (24 May 2019). “Brazil’s ‘Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão’ Wins Cannes Un Certain Regard Award”. Variety. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ “Cannes: ‘It Must Be Heaven’ Takes FIPRESCI Critics’ Prize”. The Hollywood Reporter. 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ “The 2017 Official Selection”. Cannes. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ “2017 Cannes Film Festival Announces Lineup: Todd Haynes, Sofia Coppola, ‘Twin Peaks’ and More”. IndieWire. 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ Hopewell, John (27 May 2017). “Cannes Critics Prize ‘BPM,’ Closeness,’ ‘Nothing Factory'”. Variety. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ “Андрей Кончаловский снимет фильм “Дорогие товарищи” с Юлией Высоцкой в главной роли и бюджетом в 150 миллионов рублей”. Вокруг.ТВ.

- ^ “Camera! Action!: что происходит в российском кино”. Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- ^ “Андрей Кончаловский стал кавалером ордена “За заслуги перед Италией””. www.proficinema.com.

- ^ Холоп Archived 2020-01-15 at the Wayback Machine. fond-kino.ru

- ^ “The Serf (2019)”. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ «Текст» и «Глубже» отмечены наградами «Ника» за лучший сценарий Archived 2021-12-09 at the Wayback Machine. Interfax

- ^ “Россия и Китай: делаем кино вместе” (in Russian). filmpro.

- ^ Nick Holdsworth (4 November 2013). “Russia’s ‘Stalingrad’ Storms Chinese Box Office”. The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ “Россия и Китай договорились о ста совместных проектах в медиасфере”. Ministry of Telecom and Mass Communications of the Russian Federation.

- ^ Leo Barraclough (2 November 2016). “Arnold Schwarzenegger, Jackie Chan Join Russian-Chinese Movie ‘Viy-2′”. Variety.

- ^ Patrick Frater (6 August 2015). “Russian and Chinese Companies to Co-Produce ‘Snow Queen’ Sequel”. Variety.

- ^ Vladimir Kozlov (19 May 2015). “Russian Animated Film ‘Quackerz 3D’ Gets Investment From China”. The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ “Berlin Film Festival 2020: There Is No Evil Wins Golden Bear”. Variety. 29 February 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Peter Bradshaw (30 April 2020). “DAU. Degeneration review – shocking, six-hour satire of Soviet science”. The Guardian.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (22 February 2020). “‘Persian Lessons’: Film Review”. Variety. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ “«Китобой»: подросток с Чукотки решает переплыть Берингов пролив, чтобы увидеть свою любовь в Детройте. Фильм дебютанта Филиппа Юрьева наградили в Венеции”. Archived from the original on 2020-09-30. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ “Venice Film Festival 2020 Winners: Nomadland Takes Golden Lion, Vanessa Kirby Is Best Actress”. IndieWire. 12 September 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lattanzio, Ryan (21 July 2020). “‘Sputnik’ Trailer: A Cosmonaut Brings an E.T. Invasion Back to Earth in Gory ‘Alien’ Homage”. IndieWire. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- ^ Hipes, Patrick (March 4, 2021). “Saturn Awards Nominations: ‘Star Wars: Rise Of Skywalker’, ‘Tenet’, ‘Walking Dead’, ‘Outlander’ Lead List”. Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Morg, M. (March 27, 2021). “The Silver Skates will be the first Russian film in the Netflix Originals lineup”. FREEMMORPG.TOP. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Ryabikova, Victoria (May 6, 2021). “5 reasons to watch ‘Silver Skates’ on Netflix”. Russia Beyond. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ^ Donaldson, Kayleigh (June 16, 2021). “Now On Netflix: Want to see a Russian ‘Titanic’ on Ice? ‘Silver Skates’ Has Got You Covered”. Pajiba.com. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Suyin Haynes, Madeline Roache. “Why the Film Industry Is Thriving in the Russian Wilderness”. Time.

- ^ “Yakut Films Ready to Replace Hollywood Blockbusters in Russia”. Moscow Times. 3 March 2022.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (10 June 2021). “Cannes Film Festival 2021 Lineup: Sean Baker, Wes Anderson, and More Compete for Palme d’Or”. IndieWire. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Lodge, Guy (16 July 2021). “Russian Drama ‘Unclenching the Fists’ Takes Top Prize at Cannes Un Certain Regard Awards”. Variety.

- ^ “Основной конкурс / Последняя “Милая Болгария”” [Last «Dear Bulgaria» / Poslednyaya «Milaya Bolgariya»]. Moscow International Film Festival (in Russian). 2021-04-25. Archived from the original on 2021-04-24. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ^ Georg Szalai (20 July 2021). “Locarno Film Festival Adds Two Titles to Complete Lineup”. Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Kiang, Jessica (14 August 2021). “Golden Leopard Winner ‘Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash’ Heads Impressive Slate Of Locarno Awards”. Variety. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (26 July 2021). “Venice Film Festival 2021 Full Lineup”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ “Роднянский назвал фильм “Мама, я дома” бескомпромиссным авторским высказыванием” [Rodnyansky on Bitokov’s Movie ‘Mama, I’m Home’: ‘It’s an uncompromising statement’] (in Russian). TASS. 2021-07-26. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- ^ Christopher Vourlias (2021-09-03). “Vladimir Bitokov Looks to Find a ‘Home’ in Venice With Sophomore Feature”. Variety. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- ^ Geoffrey Macnab (2021-09-02). “Alexander Rodnyansky on why this is an amazing moment for Russian filmmaking”. Screen Daily. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- ^ “Sean Penn, Wes Anderson, Ildikó Enyedi Join 2021 Cannes Lineup”. The Hollywood Reporter. 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ “Cannes Film Festival 2021 Lineup: Sean Baker, Wes Anderson, and More Compete for Palme d’Or”. IndieWire. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ “Golden Globes 2022 Non-English Language Film Submissions”. Golden Globes.

- ^ “Finnish films compete for the 2022 Golden Globe awards”. Helsinki Times. 6 December 2021.

- ^ Следствие в пяти актах

- ^ Время первого: драма о фронтовых операторах возглавила прокат

- ^ Von Seele, Emily (28 September 2021). “Fantastic Fest 2021 Review: The Execution is a Brutal Hunt for an Elusive Killer”. DailyDead.com. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Что удалось, а что — нет в фильме Ладо Кватании «Казнь»

- ^ Valerie Hopkins (May 18, 2022). “With Tchaikovsky’s Wife, Kirill Serebrennikov tackles a Russian taboo”. The New York Times.

- ^ Vladan Petkovic. “BERLINALE 2022 Panorama – Review: Convenience Store”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Michael Rosser. “Berlinale bans state-backed Russian delegations but takes “clear stand” against total boycott”. Screen Daily.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Safronova, Valeriya (April 29, 2022). “In Echo of Soviet Era, Russia’s Movie Theaters Turn to Pirate Screenings”. The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Amid Amidi (8 March 2022). “Annecy Will Not Host Any Official Russian Delegations At Its Festival”. Cartoon Brew.

- ^ Scott Roxborough (28 February 2022). “Stockholm Film Festival Bans Russian State-Backed Films, Stands With Ukraine”. Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Scott Roxborough (March 2022). “European Film Academy Joins Boycott of Russian Cinema”. Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Etan Vlessing (25 March 2022). “International Emmys Ban All Russian Programs From Competition”. Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ “Unequivocal Solidarity with Ukraine”. European Film Academy. 1 March 2022.

- ^ Haring, Bruce (March 19, 2022). “Moscow Film Festival Has Accreditation Paused By Int’l Federation Of Film Producers”.

- ^ Elsa Keslassy (March 2022). “No Russian Companies Will Attend MipTV as Organizers Will Follow ‘Government Sanction’ Against Russia”. Variety.

- ^ “Ukrainian Letters”.

- ^ Elsa Keslassy (March 2022). “Ukrainian Filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa Speaks Against Russian Boycott (EXCLUSIVE)”. Variety.

- ^ Etan Vlessing (14 March 2022). “‘Donbass’ Director Sergei Loznitsa Opposes Total Ban on Russian Cinema”. Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Mona Tavara. “Kirill Serebrennikov calls for end of “unbearable” Russian culture boycott”. Screen Daily.

- ^ Christopher Vourlias (18 May 2022). “Kirill Serebrennikov Talks Russian Boycotts, Putin’s War and Oligarch Roman Abramovich”. Variety.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Состояние российской кинематографии в 2015 году. Отчет Минкультуры”. www.proficinema.ru. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ^ “Фонд кино расширил список лидеров до 10 кинокомпаний”. www.kinometro.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ^ “Лучшие кассовые сборы в России”. www.kinopoisk.ru. Retrieved 2023-08-26.

- ^ “Крупнейшие киносети в России (включая франшизы)”. Газета “Коммерсантъ”. No. 132. 2016-07-25. p. 7. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ^ Birgit Beumers (2005). Pop Culture Russia!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. Abc-Clio. p. 76. ISBN 1-85109-459-8.

- ^ Birgit Beumers (2005). Pop Culture Russia!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. Abc-Clio. p. 75. ISBN 1-85109-459-8.

- ^ Christopher Vourlias (10 October 2021). “Rising Russian Streamer KION Unveils Originals Slate at Mipcom (EXCLUSIVE)”. Variety.

- ^ “Online streaming platforms face regulation, censorship”. The Bell. 22 November 2021.

- ^ http://www.vgik.info/international/forprospectivestudents/index.php?SECTION_ID=685 Archived 2014-07-29 at the Wayback Machine Gerasimov Institute foundation history

- ^ http://www.nyfa.edu/moscow/ Archived 2014-07-18 at the Wayback Machine NYFA Moscow

- ^ http://www.mifs.ru/index_eng.html Archived 2017-10-30 at the Wayback Machine Moscow International Film School homepage, translated