Cultural scholar Jeanne-Marie Viljoen critiques Black Panther and Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, despite their global success and celebration of African culture. She explores the complexities and shortcomings of the franchise, questioning its portrayal of African identity and the larger issues of representation in Hollywood.

What are Black Panther’s limitations when it comes to diversity?

The Black Panther films, despite their acclaim and massive cultural impact, have been critiqued for not fully representing African identity on its own nuanced terms. Rather than showcasing the true complexity of African cultures, they offer a vision of a fantastical, idealized Africa. Nevertheless, these films serve a vital purpose in opening a dialogue about racial representation in Hollywood. By casting a largely Black ensemble of talented actors, directors, and other creatives, Black Panther has significantly contributed to the conversation on race and representation within a predominantly white industry.

The franchise brought African heritage and Black excellence into mainstream Western cinema in a way few films had done before, making it a symbol of pride and inspiration for Black audiences worldwide. In front of the camera, the films showcased a rich diversity of Black talent, led by iconic actors like Chadwick Boseman, Lupita Nyong’o, Michael B. Jordan, and Danai Gurira. Behind the scenes, the film’s success allowed for increased visibility and recognition for Black filmmakers, including director Ryan Coogler.

However, as cultural studies scholar Jeanne-Marie Viljoen suggests, the representation presented in these films doesn’t fully align with African realities. While Wakanda is a fictional utopia that blends African traditions with futuristic technology, its portrayal might oversimplify or overlook the diversity and complexities of real African nations. Critics argue that while the films do a great job of countering harmful stereotypes, they don’t always capture the diversity, struggles, and complexities of African societies.

Still, the significance of the Black Panther franchise cannot be understated. It has not only provided a platform for Black talent but also prompted Hollywood to reconsider how it portrays race, culture, and identity. It has sparked a broader conversation about who gets to tell stories and whose voices are prioritized in global narratives. Through its success, the Black Panther films have become more than just movies—they are a cultural moment that has reshaped the conversation around racial representation in cinema.

In the first Black Panther film, T’Challa, portrayed by Chadwick Boseman, ascends to the throne of Wakanda, a fictional African kingdom hidden from the world. With unmatched technological advancements and a rich cultural heritage, Wakanda stands as a beacon of strength. However, T’Challa’s reign is threatened by Erik Killmonger, a vengeful outsider who challenges him for the throne. Killmonger, played by Michael B. Jordan, seeks to harness Wakanda’s resources to incite a global revolution, aiming to liberate oppressed Black people around the world. Their conflict revolves around differing philosophies about power, justice, and the responsibilities of those in control. The film explores themes of identity, legacy, and global responsibility while highlighting African culture and its diaspora.

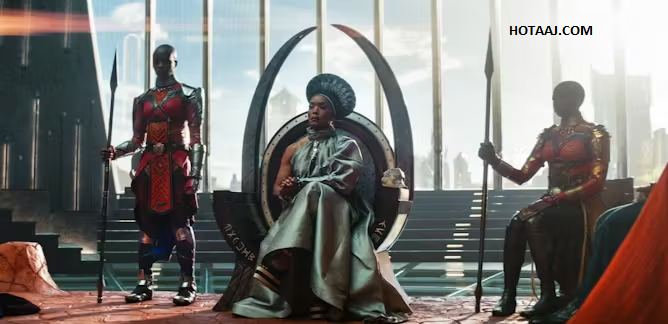

The sequel, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, picks up in the aftermath of T’Challa’s death, following the real-life passing of Chadwick Boseman. The nation of Wakanda grapples with its loss and the pressures from the outside world who are eager to exploit its resources. As tensions rise, T’Challa’s sister, Shuri (Letitia Wright), takes on the mantle of the Black Panther to protect her people and uphold her brother’s legacy. The sequel deepens the exploration of Wakanda’s culture, its geopolitical struggles, and its fight for survival against external threats, including the powerful underwater kingdom of Talokan, led by Namor. In the face of loss and shifting power dynamics, the film underscores the importance of unity, resilience, and the fight to preserve Wakanda’s legacy.

Both films combine superhero action with powerful themes of leadership, responsibility, and legacy, creating a culturally resonant narrative while continuing the broader discussion of race, identity, and empowerment in the world.

The first Black Panther film made an incredible impact, both critically and commercially, grossing over $1.3 billion worldwide and receiving widespread acclaim for its cultural significance. Over half of its box office sales came from the US market, where audiences were captivated by the film’s groundbreaking portrayal of African culture, the vibrant world of Wakanda, and its diverse cast. The visual spectacle, including the advanced technology of Wakanda, the stunning costumes, and the epic action sequences, played a significant role in the film’s success. These elements catered to Hollywood’s traditional formula for blockbuster entertainment: flashy, high-budget spectacles that deliver both action and excitement.

However, while the visual elements of Black Panther captivated audiences, they often obscured the deeper content embedded in the story. Hollywood’s investment in the film was largely driven by a narrow western understanding of spectacle—one that prioritizes visually engaging content over cultural depth. US audiences were fascinated by the technological marvels and the dramatic action, which contributed to the film’s massive success in the western market. Yet, for many African and African diaspora viewers, Black Panther’s portrayal of Africa as a land of unimagined wealth and advanced technology, while fictional and inspiring, did not capture the full complexity of the real African continent or the struggles it faces in the modern world.

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, while not achieving the same level of box office success as its predecessor, saw its biggest successes in global markets. This reflects a shift in the way the film was received: its narrative of loss and resilience resonated deeply with international audiences, particularly in parts of Africa and among the African diaspora. Yet, even with this broader appeal, the focus on visual spectacle often overshadowed the more complex issues addressed in the film—such as the fight for sovereignty, global exploitation, and the preservation of cultural identity.

Ultimately, the success of these films highlights a tendency in Hollywood to prioritize entertainment value and visual appeal at the expense of truly engaging with the complex histories and cultures of Africa and the Black diaspora. While Black Panther undoubtedly brought much-needed representation and discussion of race and identity to the forefront, it is important to recognize that the spectacle often distances audiences from fully appreciating the deeper issues of African heritage, diversity, and the political realities faced by African nations.

The reception of Black Panther and similar films has highlighted a key challenge in Hollywood’s approach to diversity: while the films themselves provide a significant cultural breakthrough, their success has been framed in such a way that it might have inadvertently slowed further progress. The broader response, particularly from Hollywood audiences, often focuses on the visual spectacle and cultural representation, but does not necessarily translate into long-term systemic change within the industry.

In particular, the success of Black Panther—despite its groundbreaking representation of Black talent and African culture—has been framed by Hollywood audiences as a “solution” to diversity issues. This has led to a situation where a significant portion of American filmgoers, particularly those who are less engaged with the nuances of racial and cultural representation, believe that diversity in cinema has already been addressed. In fact, a 2019 Hollywood Diversity Report cited Black Panther as a case where the power of diverse images led to 42% of American spectators believing that enough has been done about diversity in Hollywood.

This perception can be counterproductive. It may give the impression that the issue of representation has been solved, when, in reality, the deeper structural issues of inclusion, opportunity, and authentic storytelling still persist in the industry. While Black Panther was a milestone for Black representation in blockbuster films, it also risked allowing Hollywood to believe that this one film was enough to address the wider challenges of diversity. It provided a token image of diversity, yet left untouched the underlying mechanisms that continue to marginalize minority voices, both in front of and behind the camera.

By framing these films as definitive examples of progress, Hollywood audiences may have become complacent, overlooking the need for continued efforts to diversify storytelling, production, and leadership within the industry. In a sense, Black Panther has created a false sense of accomplishment, which, instead of pushing Hollywood towards further decolonization of its mainstream imagination, has instead entrenched the belief that one success story is all that’s needed to solve complex issues of racial and cultural inequality.

In order to truly achieve diversity and decolonization, the entertainment industry must look beyond the spectacle and focus on creating a more inclusive, equitable system that allows for a wider range of stories to be told—stories that go beyond the symbolic representation of Black culture, and instead foster a true understanding of diverse experiences. Without this shift, the celebration of films like Black Panther may inadvertently perpetuate the illusion that enough has been done, when much more work remains to be done to ensure genuine diversity and representation in Hollywood.

COURTESY: Marvel Entertainment

Indeed, the spectacle-driven success of Black Panther and similar films in Hollywood can unintentionally lull audiences into a false sense of progress. By presenting a flashy and entertaining version of African culture, these films may lead spectators to feel that they have “seen” Africa or have a general understanding of African experiences—without needing to engage with the deeper, more nuanced realities of African storytelling, filmmaking, or culture. This phenomenon is particularly evident when it comes to audiences in the West who view these films primarily through a lens of entertainment and spectacle, rather than a means of engaging with the lived experiences of African people.

This limited engagement with Africa is starkly highlighted when comparing Hollywood’s portrayal of African cultures with the vibrant diversity of African cinema, such as Nollywood—Nigeria’s booming film industry. Nollywood’s films often reflect a different, more localized cultural identity, offering a distinct portrayal of African life that does not fit neatly into the Western definitions of spectacle or commercial success. These films may tackle issues such as poverty, tradition, modernity, and complex socio-political dynamics that are often left out of the more mainstream Hollywood narratives.

The focus on a few high-budget, blockbuster representations of Africa may inadvertently reinforce stereotypes or oversimplify African identity, making it difficult for Hollywood audiences to appreciate the full depth and diversity of African cinema. While Black Panther presents an imagined, technologically advanced African nation, Nollywood and other African film industries are concerned with telling grounded, complex stories that reflect the multifaceted realities of life on the continent.

This disconnect also limits Hollywood’s approach to filmmaking about African topics, shaping the kinds of stories that get made and the way they are told. When the global spotlight is only on films like Black Panther, there is less room for stories from other parts of the African diaspora or films that explore issues from a more intimate, grassroots perspective. In turn, this restricts the scope of African narratives in global cinema and the types of opportunities afforded to African filmmakers and audiences.

Ultimately, if Hollywood audiences continue to accept only the spectacle as a substitute for deeper understanding, the risk is that the portrayal of African cultures and experiences will remain incomplete. This will not only limit the diversity of stories told about Africa, but also undermine the potential for films that genuinely explore the richness of African history, politics, and everyday life. What’s needed is a broader cultural investment—one that goes beyond the surface level and embraces a more diverse and multifaceted understanding of Africa and its filmmakers.

What can Hollywood learn from how the films have been received in Africa?

The use of African cultural markers in Black Panther, such as the incorporation of costumes inspired by traditional African attire and the use of languages like isiXhosa, is undoubtedly significant in its representation of African heritage on the global stage. However, this use of cultural elements raises critical questions about cultural appropriation and the extent to which the film truly engages with African cultures in an authentic and meaningful way.

By selectively incorporating certain visual elements from various African cultures—like the lip plates, neck rings, and Kente cloth—Black Panther borrows from these symbols without necessarily providing the context or background that would allow audiences to fully appreciate their significance. While these cultural markers may be striking and visually appealing, they risk being reduced to superficial or exoticized representations. This approach can inadvertently suggest that Africa, with its vast diversity of languages, traditions, and histories, can be distilled into a set of popular and easily recognizable symbols that are interchangeable.

Critics of Black Panther point out that many viewers, particularly those unfamiliar with African cultures, may not even realize that the film’s characters speak isiXhosa or that certain garments are based on Ghanaian Kente cloth. The lack of explanation or deeper engagement with these cultural markers may result in audiences seeing them as mere aesthetic choices rather than as part of a larger, complex cultural and historical context. This raises concerns about how much Hollywood truly understands or respects the cultures it seeks to portray, and whether such representations serve to educate audiences or merely capitalize on the visual appeal of African culture.

Moreover, Black Panther’s treatment of African culture—while groundbreaking in some respects—still falls short of real empowerment. True empowerment, as critics suggest, would involve a more direct engagement with African political, social, and economic issues. It would mean telling stories that address the struggles and triumphs of African nations and peoples in a more nuanced and authentic manner, not just through the lens of spectacle. This could involve focusing on the real challenges facing African societies today, such as colonial legacies, political corruption, economic disparity, and the fight for environmental justice, among others.

Hollywood’s focus on profit and spectacle often undermines these deeper, more complex narratives. In the case of Black Panther, the film’s commercial success and emphasis on visual spectacle sometimes overshadow the possibility of using the platform to explore more meaningful, politically charged stories about Africa and its people. As long as Hollywood continues to treat African cultures as a backdrop for high-budget entertainment rather than a source of authentic storytelling, real empowerment will remain elusive.

For true empowerment, Hollywood—and the film industry at large—must shift from a model of cultural appropriation to one of cultural collaboration. This means not only drawing from African cultures for aesthetic appeal but also involving African filmmakers, actors, and storytellers in the creative process. It also means ensuring that the stories told are rooted in the real experiences of African people and that the power to tell those stories is not just in the hands of Western creators, but also in the hands of Africans themselves. Only through such engagement can Hollywood contribute to a more equitable and authentic representation of Africa on the global stage.

The success of Black Panther: Wakanda Forever in Nigeria, where it became the highest-grossing film ever at the Nigerian box office and the first to earn one billion naira, is a testament to the more nuanced way Nollywood audiences engage with films that depict Africa. Unlike Hollywood audiences, who may view the film through a lens that prioritizes spectacle over substance, Nigerian viewers—and African audiences more broadly—are likely to interpret the film’s themes and cultural representations with a deeper understanding of Africa’s complexities.

This distinction highlights a key difference in how spectacle and entertainment are received in different cultural contexts. Nollywood, with its rich history of producing films that are both entertaining and socially relevant, has fostered an audience that is attuned to the political, social, and cultural implications of what they watch. Nollywood films often address pressing issues such as corruption, social inequality, and the impact of colonialism, blending these themes with entertainment in ways that resonate with African audiences’ lived experiences.

In contrast, Hollywood often operates within a framework that prioritizes global appeal, which can sometimes result in superficial portrayals of African culture that gloss over its diversity and complexity. While Black Panther and its sequel have undeniably been important milestones in terms of racial representation, they still fall short of offering the kind of deep, culturally specific storytelling that Nollywood audiences are accustomed to.

For Nigerian audiences, Wakanda Forever may have been viewed not just as an exciting superhero movie, but also as a story about power, identity, and resistance—a reflection of the political struggles that many African nations face today. The film’s depiction of a technologically advanced African nation could have resonated with Nigerians who see parallels in their own country’s potential for innovation and progress, despite the challenges it faces. Furthermore, the fact that the film was celebrated and embraced by African audiences suggests that, despite its limitations in terms of cultural authenticity, there is still a hunger for films that portray Africa in a powerful, positive light.

This success also underscores the importance of considering African audiences in global film markets. As African filmmakers continue to gain recognition and as Nollywood continues to thrive, there is a growing recognition that African audiences are not just passive consumers of Hollywood’s narratives, but active participants in the global conversation about race, identity, and representation. Wakanda Forever’s success in Nigeria serves as a reminder that African audiences bring a more sophisticated understanding of spectacle, one that is informed by their own histories, cultures, and struggles.

Ultimately, while Black Panther: Wakanda Forever may not have fully embraced a nuanced and authentic portrayal of Africa, its success in Nigeria demonstrates that African audiences are eager for stories that reflect their realities. Moving forward, Hollywood could benefit from engaging more deeply with African filmmakers and audiences to create films that do justice to the continent’s rich cultural diversity and complex political landscape. By doing so, it would not only ensure a more authentic representation of Africa but also tap into a burgeoning market that is eager for films that speak to their experiences and aspirations.

Nollywood’s distinctive conventions around cinematic spectacle offer a deeper engagement with socio-cultural and socio-economic issues, a contrast to Hollywood’s more superficial focus on visual appeal. While Hollywood often prioritizes spectacle as a form of entertainment—focusing on grandiose visuals and action-packed sequences—Nollywood films are designed to both entertain and spark reflection on the challenges faced by Nigerian and broader African societies. In this way, Nollywood blockbusters often blend visual spectacle with meaningful commentary on issues like poverty, corruption, family dynamics, and social inequality, encouraging audiences to engage critically with their own lived experiences.

This approach is especially evident in the portrayal of Afro-superheroes in African cinema. Rather than being mere vehicles for fantasy and escapism, these characters are framed within the context of real-world struggles and aspirations. Afro-superheroes are often seen as symbolic figures who represent hope, resilience, and resistance in the face of adversity. They offer more than just a temporary escape from reality—they become vehicles for social commentary and political discourse. African audiences, familiar with the complexities of their own political and social landscapes, interpret these characters not just as larger-than-life figures but as representations of the potential for transformative change within their societies.

In this context, films like Black Panther and its sequel Wakanda Forever hold a different meaning when viewed by African audiences. These films, despite their imperfections and occasional misrepresentation, become a resource for imaginative transformation. African critics argue that Wakanda, as depicted in these films, is not merely a fantastical kingdom but a metaphor for the possibilities that Africa could achieve if it were able to harness its own resources, knowledge, and power. It taps into the desire for a reimagined African future—one where the continent is not only rich in culture but also technologically advanced and politically empowered.

This interpretation of Wakanda as a symbol of hope and transformation is in stark contrast to how it might be perceived by Hollywood audiences, who may view the spectacle more as an exotic adventure or entertainment. For African audiences, however, the potential for transformation through films like Black Panther transcends the superficial layers of spectacle. They see in Wakanda the embodiment of a future where African countries are no longer dependent on external powers but instead are able to build their own legacy, much like the fictional kingdom in the film.

This critical perspective also reflects the broader struggle within African cinema and media to move beyond mere representations of exoticism or novelty. African filmmakers and critics are pushing for a cinema that engages with the complexities of African identity, history, and politics. Nollywood, as a key player in African film production, plays an essential role in this shift. By incorporating both spectacle and social critique, Nollywood is reshaping the way African cinema is understood and consumed—not only by African audiences but also by international viewers who are increasingly aware of the need for authentic representation.

Ultimately, the fusion of spectacle and socio-political engagement in Nollywood films represents a more holistic approach to filmmaking—one that is rooted in the lived experiences of African people and the desire to reflect, critique, and transform the world around them. This engagement with African socio-political realities is what sets Nollywood apart from Hollywood and makes it an essential part of the global conversation about cinema, race, and representation.

This distinction between Hollywood and Nollywood audiences’ reception of Wakanda Forever can be attributed to how each group interprets and interacts with the film’s political themes. While Hollywood audiences may view the spectacle as an isolated form of entertainment, Nollywood audiences bring their own cultural context and sophisticated understanding of cinema into their viewing experience. For Nigerian viewers, the film’s portrayal of political struggles, even if limited, resonates in ways that go beyond the surface-level spectacle. Nollywood audiences are accustomed to engaging with socio-political issues in their films, where entertainment often serves as a vehicle for discussing real-world challenges.

In this context, Wakanda Forever is not just a superhero spectacle but also a space for reflecting on African political dynamics and aspirations. The film, while still limited in its portrayal of these themes, allows Nigerian viewers to engage with the concept of African futurism—the idea of a reimagined future for the continent, one where Africans are not only technologically advanced but also empowered politically. Nollywood, with its rich tradition of addressing social and political issues, has cultivated an audience that is more comfortable with this form of engagement. These viewers are eager to explore and discuss the political undertones of the film, using it as a tool to build knowledge and expand their understanding of African identity, power, and possibility.

This kind of engagement is key to how Nollywood audiences perceive films like Wakanda Forever. The film becomes a point of connection between entertainment and political discourse, encouraging deeper conversations about Africa’s role in the global political landscape. It encourages the exploration of what it means to build an African future that is self-sustaining, free from colonial influence, and rooted in the continent’s own cultural, social, and technological advancements.

For Nollywood viewers, the film serves as a springboard for imagining the potential of Africa, both in the real world and within the realm of speculative fiction. They see the fictional Wakanda not just as a mythical place but as an inspiration for what Africa could achieve if it harnessed its full potential. This engagement with African futurism is not simply about wishful thinking but also about building political knowledge—by understanding the structural challenges that impede Africa’s progress, Nollywood audiences can begin to imagine and work towards transformative change.

Thus, while Wakanda Forever may have an unrealistic portrayal of Africa in some respects, its political themes strike a chord with Nollywood audiences who are keen to engage with the film’s ideas on a deeper level. This intersection of spectacle and political knowledge-building reflects the ways in which Nollywood has shaped its audience’s approach to cinema—one that values not just entertainment but also the opportunity for critical reflection and political engagement.

Why should Hollywood look to Africa for a better future?

Hollywood’s narrow focus on its own audience has, for too long, shaped its approach to films about diversity and inclusion. While Black Panther and Wakanda Forever have made significant strides in representation, Hollywood has often viewed these films primarily as spectacles for Western audiences, reinforcing the idea that diversity has been addressed simply through the visual presence of Black characters and talent. However, this limited approach overlooks the richness and complexity of African cinema and audiences, who engage with these films in a way that is more deeply embedded in the political, cultural, and social realities of the continent.

African audiences, particularly those in Nigeria with Nollywood, bring a far more nuanced understanding to films like Wakanda Forever. Their approach to cinematic spectacle is not just about the visual thrills but about how films reflect and engage with the lived experiences, struggles, and political realities of the people. This includes an appreciation for how cinema can function as both entertainment and a tool for political and social reflection. Nollywood has developed its own conventions around cinematic storytelling, where spectacle is not divorced from the political and social issues it portrays. In these films, Afro-superheroes and the broader narratives often resonate on a deeper level, not just as escapism but as tools for political engagement and knowledge building about Africa’s future.

By continuing to focus predominantly on the Western audience and market, Hollywood not only misses out on the intellectual and cultural contributions that African cinema and its audiences can offer, but it also risks reinforcing the idea that only superficial changes in representation—like casting Black actors in prominent roles—are sufficient. This limits both the films themselves and the broader conversation about diversity and inclusion. In a world that is increasingly interconnected, Hollywood has an opportunity to engage with African audiences not just as consumers of spectacle but as active participants in shaping how diversity is understood and represented in film.

For Hollywood to truly decolonize its approach to cinema, it must look beyond its own borders and engage with African filmmakers and audiences, who have long understood the intersection of cinema, politics, and society in a way that is far more sophisticated than what is often seen in Hollywood blockbusters. By incorporating African perspectives into its storytelling, Hollywood could both expand its creative horizons and contribute to a more meaningful and authentic representation of diversity, one that goes beyond surface-level inclusivity and into the deeper issues of identity, power, and cultural relevance.

In this sense, Hollywood’s engagement with African audiences and filmmakers is not just about selling tickets but about learning from a more complex, politically-engaged approach to filmmaking that truly represents the diversity of the world. By embracing this opportunity, Hollywood can broaden its understanding of what cinema can do—not just as a form of entertainment, but as a powerful tool for building global knowledge, fostering real inclusion, and reimagining the future of storytelling in a way that reflects the full richness of human experience.

Hollywood’s limited engagement with African audiences and filmmakers significantly narrows the scope of the social problems it addresses and the types of films it produces. By focusing primarily on Western perspectives, Hollywood misses an opportunity to explore the diverse and complex issues that are deeply embedded in African cultures and societies. Africa, with its rich history, vast cultural landscapes, and powerful contemporary narratives, is a global leader in the arts. Its vibrant cinema industries, like Nollywood, offer a unique lens through which social, political, and cultural issues are explored in ways that Hollywood has yet to fully embrace.

If Hollywood were to take African audiences and filmmakers into account, it could enrich the conversation around diversity and inclusion in ways that go beyond token representation or surface-level spectacle. African filmmakers and audiences have a profound understanding of how film can be a tool for social change, offering nuanced perspectives on race, identity, power, and the complexities of history. By tapping into these insights, Hollywood could create films that challenge stereotypes, explore new social problems, and offer fresh narratives that resonate with global audiences.

African cinema is not just about showcasing Black talent; it is also about tackling real-world issues that Hollywood has often shied away from. From the political struggles in South Africa during apartheid to the socio-economic challenges faced by people across the continent today, African filmmakers have consistently used their craft to engage with and reflect on the realities of their societies. This is an opportunity Hollywood can’t afford to overlook if it truly wants to contribute to the broader conversation on diversity and inclusion.

By expanding its lens to incorporate African perspectives, Hollywood could move beyond the repetitive spectacle of superhero films and begin telling stories that are rich with political, social, and cultural significance. This would not only create a more inclusive and diverse cinematic landscape but also elevate global storytelling. The future of cinema lies in recognizing and amplifying the voices of underrepresented communities—communities like Africa, whose contributions to the arts have long been undervalued.

In conclusion, Hollywood’s potential for true diversity and inclusion hinges on a more authentic and thoughtful engagement with African cinema and audiences. This engagement would allow Hollywood to tackle a wider array of social problems and offer audiences films that are not only entertaining but also thought-provoking and socially relevant. By moving past the familiar, formulaic spectacles of superhero blockbusters, Hollywood can learn from Africa’s cinematic richness and create a more inclusive, globally aware film industry.

References

- ^ “Facts About Nigerian Movies and History”. Total Facts about Nigeria. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onikeku, Qudus (January 2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. The Journal of Human Communications: A Journal of …. Academia. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onuzulike, Uchenna (2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. Nollywood Journal. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Igwe, Charles (6 November 2015). “How Nollywood became the second largest film industry”. BritichCouncil.com.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002). “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”. New York Times.

- ^ “History of Nollywood”. Nificon. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Ayengho, Alex (23 June 2012). “INSIDE NOLLYWOOD: What is Nollywood?”. E24-7 Magazine. NovoMag. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “”Nollywood”: What’s in a Name?”. Nigeria Village Square. 3 July 2005. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Apara, Seun (22 September 2013). “Nollywood at 20: Half Baked Idea”. 360Nobs.com. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Izorya, Stanislaus (January 2017). “Nollywood in Diversity for IJC”. International Journal of Communication (21): 37–46.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002), “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”, The New York Times, retrieved 21 September 2023

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Yoruba Movies | Yoruba Films”. Yoruba Movies. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Sheme, Ibrahim (13 December 2010). “Bahaushe Mai Ban Haushi”. Ibrahimsheme.blogspot.com. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Gana, Babagana M. (1 June 2012). “Hausa-English code-switching in Kanywood Films”. International Journal of Linguistics. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ “Nollywood: Lights, camera, Africa”. The Economist. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood Producers Guild USA Kick off Film Production With Arrival of Annie Macaulay Idibia”.

- ^ “Nollywood USA emerging”. 8 June 2013.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen (23 May 2013). “Nollywood USA: African Movie Makers Expand Filming to D.C. Area”. The Washington Post.

- ^ “Stolen, a Nollywood-USA movie by Robert Peters”. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012.

- ^ Miller, Jade L. (3 June 2016). Nollywood Central: The Nigerian Videofilm Industry. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84457-694-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Husseini, Shaibu. “A YEAR OF MIXED FORTUNES FOR NOLLYWOOD”. Ehizoya Films. Ehizoya Golden Entertainment. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Olamide (31 December 2013). “Group Wants ‘Nollywood’ Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. yabaleftonline.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ “NOLLYWOODTUBE”. NOLLYWOODTUBE. 12 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Ekeanyanwu, Nnamdi Tobechukwu. “Nollywood, New Communication Technologies and Indigenous Cultures in a Globalized World: The NigerianDilemma”. Covenant University. Department of Mass Communication, College of Human Development. Retrieved 20 February 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Angelo, Mike (30 November 2013). “Nollywood At 20: Organisers’ Flaws… Top Names Erased From Award List”. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Tolu (1 January 2014). “Why ‘Nollywood’ Has to be Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. Information Nigeria. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Bada, Gbenga. “Hon. Rotimi Makinde sparks off controversy over Nollywood @ 20 celebrations”. MOMO. Movie Moments. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ McCain, Carmen (30 July 2011). “NOLLYWOOD AND ITS TERMINOLOGY MIGRAINES”. NigeriaFilms.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood New releases in 2021”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Oyeniya, Adegboyega (8 November 2013). “Nollywood at 20?”. The Punch Newspaper. The Punch NG. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nigeria: October 1 Will Open New Chapter in My Life – Kunle Afolayan”. allAfrica.com. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.References

- [edit]

- ^ “Facts About Nigerian Movies and History”. Total Facts about Nigeria. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onikeku, Qudus (January 2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. The Journal of Human Communications: A Journal of …. Academia. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onuzulike, Uchenna (2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. Nollywood Journal. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Igwe, Charles (6 November 2015). “How Nollywood became the second largest film industry”. BritichCouncil.com.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002). “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”. New York Times.

- ^ “History of Nollywood”. Nificon. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Ayengho, Alex (23 June 2012). “INSIDE NOLLYWOOD: What is Nollywood?”. E24-7 Magazine. NovoMag. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “”Nollywood”: What’s in a Name?”. Nigeria Village Square. 3 July 2005. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Apara, Seun (22 September 2013). “Nollywood at 20: Half Baked Idea”. 360Nobs.com. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Izorya, Stanislaus (January 2017). “Nollywood in Diversity for IJC”. International Journal of Communication (21): 37–46.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002), “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”, The New York Times, retrieved 21 September 2023

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Yoruba Movies | Yoruba Films”. Yoruba Movies. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Sheme, Ibrahim (13 December 2010). “Bahaushe Mai Ban Haushi”. Ibrahimsheme.blogspot.com. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Gana, Babagana M. (1 June 2012). “Hausa-English code-switching in Kanywood Films”. International Journal of Linguistics. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ “Nollywood: Lights, camera, Africa”. The Economist. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood Producers Guild USA Kick off Film Production With Arrival of Annie Macaulay Idibia”.

- ^ “Nollywood USA emerging”. 8 June 2013.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen (23 May 2013). “Nollywood USA: African Movie Makers Expand Filming to D.C. Area”. The Washington Post.

- ^ “Stolen, a Nollywood-USA movie by Robert Peters”. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012.

- ^ Miller, Jade L. (3 June 2016). Nollywood Central: The Nigerian Videofilm Industry. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84457-694-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Husseini, Shaibu. “A YEAR OF MIXED FORTUNES FOR NOLLYWOOD”. Ehizoya Films. Ehizoya Golden Entertainment. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Olamide (31 December 2013). “Group Wants ‘Nollywood’ Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. yabaleftonline.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ “NOLLYWOODTUBE”. NOLLYWOODTUBE. 12 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Ekeanyanwu, Nnamdi Tobechukwu. “Nollywood, New Communication Technologies and Indigenous Cultures in a Globalized World: The NigerianDilemma”. Covenant University. Department of Mass Communication, College of Human Development. Retrieved 20 February 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Angelo, Mike (30 November 2013). “Nollywood At 20: Organisers’ Flaws… Top Names Erased From Award List”. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Tolu (1 January 2014). “Why ‘Nollywood’ Has to be Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. Information Nigeria. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Bada, Gbenga. “Hon. Rotimi Makinde sparks off controversy over Nollywood @ 20 celebrations”. MOMO. Movie Moments. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ McCain, Carmen (30 July 2011). “NOLLYWOOD AND ITS TERMINOLOGY MIGRAINES”. NigeriaFilms.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood New releases in 2021”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Oyeniya, Adegboyega (8 November 2013). “Nollywood at 20?”. The Punch Newspaper. The Punch NG. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nigeria: October 1 Will Open New Chapter in My Life – Kunle Afolayan”. allAfrica.com. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- References

- [edit]

- ^ “Facts About Nigerian Movies and History”. Total Facts about Nigeria. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onikeku, Qudus (January 2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. The Journal of Human Communications: A Journal of …. Academia. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onuzulike, Uchenna (2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. Nollywood Journal. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Igwe, Charles (6 November 2015). “How Nollywood became the second largest film industry”. BritichCouncil.com.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002). “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”. New York Times.

- ^ “History of Nollywood”. Nificon. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Ayengho, Alex (23 June 2012). “INSIDE NOLLYWOOD: What is Nollywood?”. E24-7 Magazine. NovoMag. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “”Nollywood”: What’s in a Name?”. Nigeria Village Square. 3 July 2005. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Apara, Seun (22 September 2013). “Nollywood at 20: Half Baked Idea”. 360Nobs.com. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Izorya, Stanislaus (January 2017). “Nollywood in Diversity for IJC”. International Journal of Communication (21): 37–46.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002), “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”, The New York Times, retrieved 21 September 2023

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Yoruba Movies | Yoruba Films”. Yoruba Movies. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Sheme, Ibrahim (13 December 2010). “Bahaushe Mai Ban Haushi”. Ibrahimsheme.blogspot.com. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Gana, Babagana M. (1 June 2012). “Hausa-English code-switching in Kanywood Films”. International Journal of Linguistics. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ “Nollywood: Lights, camera, Africa”. The Economist. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood Producers Guild USA Kick off Film Production With Arrival of Annie Macaulay Idibia”.

- ^ “Nollywood USA emerging”. 8 June 2013.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen (23 May 2013). “Nollywood USA: African Movie Makers Expand Filming to D.C. Area”. The Washington Post.

- ^ “Stolen, a Nollywood-USA movie by Robert Peters”. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012.

- ^ Miller, Jade L. (3 June 2016). Nollywood Central: The Nigerian Videofilm Industry. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84457-694-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Husseini, Shaibu. “A YEAR OF MIXED FORTUNES FOR NOLLYWOOD”. Ehizoya Films. Ehizoya Golden Entertainment. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Olamide (31 December 2013). “Group Wants ‘Nollywood’ Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. yabaleftonline.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ “NOLLYWOODTUBE”. NOLLYWOODTUBE. 12 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Ekeanyanwu, Nnamdi Tobechukwu. “Nollywood, New Communication Technologies and Indigenous Cultures in a Globalized World: The NigerianDilemma”. Covenant University. Department of Mass Communication, College of Human Development. Retrieved 20 February 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Angelo, Mike (30 November 2013). “Nollywood At 20: Organisers’ Flaws… Top Names Erased From Award List”. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Tolu (1 January 2014). “Why ‘Nollywood’ Has to be Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. Information Nigeria. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Bada, Gbenga. “Hon. Rotimi Makinde sparks off controversy over Nollywood @ 20 celebrations”. MOMO. Movie Moments. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ McCain, Carmen (30 July 2011). “NOLLYWOOD AND ITS TERMINOLOGY MIGRAINES”. NigeriaFilms.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood New releases in 2021”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Oyeniya, Adegboyega (8 November 2013). “Nollywood at 20?”. The Punch Newspaper. The Punch NG. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nigeria: October 1 Will Open New Chapter in My Life – Kunle Afolayan”. allAfrica.com. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- References

- [edit]

- ^ “Facts About Nigerian Movies and History”. Total Facts about Nigeria. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onikeku, Qudus (January 2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. The Journal of Human Communications: A Journal of …. Academia. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onuzulike, Uchenna (2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. Nollywood Journal. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Igwe, Charles (6 November 2015). “How Nollywood became the second largest film industry”. BritichCouncil.com.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002). “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”. New York Times.

- ^ “History of Nollywood”. Nificon. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Ayengho, Alex (23 June 2012). “INSIDE NOLLYWOOD: What is Nollywood?”. E24-7 Magazine. NovoMag. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “”Nollywood”: What’s in a Name?”. Nigeria Village Square. 3 July 2005. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Apara, Seun (22 September 2013). “Nollywood at 20: Half Baked Idea”. 360Nobs.com. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Izorya, Stanislaus (January 2017). “Nollywood in Diversity for IJC”. International Journal of Communication (21): 37–46.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002), “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”, The New York Times, retrieved 21 September 2023

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Yoruba Movies | Yoruba Films”. Yoruba Movies. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Sheme, Ibrahim (13 December 2010). “Bahaushe Mai Ban Haushi”. Ibrahimsheme.blogspot.com. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Gana, Babagana M. (1 June 2012). “Hausa-English code-switching in Kanywood Films”. International Journal of Linguistics. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ “Nollywood: Lights, camera, Africa”. The Economist. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood Producers Guild USA Kick off Film Production With Arrival of Annie Macaulay Idibia”.

- ^ “Nollywood USA emerging”. 8 June 2013.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen (23 May 2013). “Nollywood USA: African Movie Makers Expand Filming to D.C. Area”. The Washington Post.

- ^ “Stolen, a Nollywood-USA movie by Robert Peters”. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012.

- ^ Miller, Jade L. (3 June 2016). Nollywood Central: The Nigerian Videofilm Industry. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84457-694-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Husseini, Shaibu. “A YEAR OF MIXED FORTUNES FOR NOLLYWOOD”. Ehizoya Films. Ehizoya Golden Entertainment. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Olamide (31 December 2013). “Group Wants ‘Nollywood’ Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. yabaleftonline.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ “NOLLYWOODTUBE”. NOLLYWOODTUBE. 12 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Ekeanyanwu, Nnamdi Tobechukwu. “Nollywood, New Communication Technologies and Indigenous Cultures in a Globalized World: The NigerianDilemma”. Covenant University. Department of Mass Communication, College of Human Development. Retrieved 20 February 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Angelo, Mike (30 November 2013). “Nollywood At 20: Organisers’ Flaws… Top Names Erased From Award List”. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Tolu (1 January 2014). “Why ‘Nollywood’ Has to be Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. Information Nigeria. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Bada, Gbenga. “Hon. Rotimi Makinde sparks off controversy over Nollywood @ 20 celebrations”. MOMO. Movie Moments. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ McCain, Carmen (30 July 2011). “NOLLYWOOD AND ITS TERMINOLOGY MIGRAINES”. NigeriaFilms.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood New releases in 2021”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Oyeniya, Adegboyega (8 November 2013). “Nollywood at 20?”. The Punch Newspaper. The Punch NG. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nigeria: October 1 Will Open New Chapter in My Life – Kunle Afolayan”. allAfrica.com. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- References

- [edit]

- ^ “Facts About Nigerian Movies and History”. Total Facts about Nigeria. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onikeku, Qudus (January 2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. The Journal of Human Communications: A Journal of …. Academia. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onuzulike, Uchenna (2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. Nollywood Journal. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Igwe, Charles (6 November 2015). “How Nollywood became the second largest film industry”. BritichCouncil.com.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002). “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”. New York Times.

- ^ “History of Nollywood”. Nificon. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Ayengho, Alex (23 June 2012). “INSIDE NOLLYWOOD: What is Nollywood?”. E24-7 Magazine. NovoMag. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “”Nollywood”: What’s in a Name?”. Nigeria Village Square. 3 July 2005. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Apara, Seun (22 September 2013). “Nollywood at 20: Half Baked Idea”. 360Nobs.com. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Izorya, Stanislaus (January 2017). “Nollywood in Diversity for IJC”. International Journal of Communication (21): 37–46.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002), “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”, The New York Times, retrieved 21 September 2023

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Yoruba Movies | Yoruba Films”. Yoruba Movies. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Sheme, Ibrahim (13 December 2010). “Bahaushe Mai Ban Haushi”. Ibrahimsheme.blogspot.com. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Gana, Babagana M. (1 June 2012). “Hausa-English code-switching in Kanywood Films”. International Journal of Linguistics. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ “Nollywood: Lights, camera, Africa”. The Economist. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood Producers Guild USA Kick off Film Production With Arrival of Annie Macaulay Idibia”.

- ^ “Nollywood USA emerging”. 8 June 2013.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen (23 May 2013). “Nollywood USA: African Movie Makers Expand Filming to D.C. Area”. The Washington Post.

- ^ “Stolen, a Nollywood-USA movie by Robert Peters”. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012.

- ^ Miller, Jade L. (3 June 2016). Nollywood Central: The Nigerian Videofilm Industry. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84457-694-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Husseini, Shaibu. “A YEAR OF MIXED FORTUNES FOR NOLLYWOOD”. Ehizoya Films. Ehizoya Golden Entertainment. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Olamide (31 December 2013). “Group Wants ‘Nollywood’ Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. yabaleftonline.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ “NOLLYWOODTUBE”. NOLLYWOODTUBE. 12 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Ekeanyanwu, Nnamdi Tobechukwu. “Nollywood, New Communication Technologies and Indigenous Cultures in a Globalized World: The NigerianDilemma”. Covenant University. Department of Mass Communication, College of Human Development. Retrieved 20 February 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Angelo, Mike (30 November 2013). “Nollywood At 20: Organisers’ Flaws… Top Names Erased From Award List”. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Tolu (1 January 2014). “Why ‘Nollywood’ Has to be Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. Information Nigeria. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Bada, Gbenga. “Hon. Rotimi Makinde sparks off controversy over Nollywood @ 20 celebrations”. MOMO. Movie Moments. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ McCain, Carmen (30 July 2011). “NOLLYWOOD AND ITS TERMINOLOGY MIGRAINES”. NigeriaFilms.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood New releases in 2021”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Oyeniya, Adegboyega (8 November 2013). “Nollywood at 20?”. The Punch Newspaper. The Punch NG. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nigeria: October 1 Will Open New Chapter in My Life – Kunle Afolayan”. allAfrica.com. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- References

- [edit]

- ^ “Facts About Nigerian Movies and History”. Total Facts about Nigeria. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onikeku, Qudus (January 2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. The Journal of Human Communications: A Journal of …. Academia. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Onuzulike, Uchenna (2007). “Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture”. Nollywood Journal. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Igwe, Charles (6 November 2015). “How Nollywood became the second largest film industry”. BritichCouncil.com.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002). “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”. New York Times.

- ^ “History of Nollywood”. Nificon. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Ayengho, Alex (23 June 2012). “INSIDE NOLLYWOOD: What is Nollywood?”. E24-7 Magazine. NovoMag. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “”Nollywood”: What’s in a Name?”. Nigeria Village Square. 3 July 2005. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Apara, Seun (22 September 2013). “Nollywood at 20: Half Baked Idea”. 360Nobs.com. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Izorya, Stanislaus (January 2017). “Nollywood in Diversity for IJC”. International Journal of Communication (21): 37–46.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (16 September 2002), “Step Aside, L.A. and Bombay, for Nollywood”, The New York Times, retrieved 21 September 2023

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Yoruba Movies | Yoruba Films”. Yoruba Movies. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Sheme, Ibrahim (13 December 2010). “Bahaushe Mai Ban Haushi”. Ibrahimsheme.blogspot.com. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ Gana, Babagana M. (1 June 2012). “Hausa-English code-switching in Kanywood Films”. International Journal of Linguistics. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013.

- ^ “Nollywood: Lights, camera, Africa”. The Economist. 16 December 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood Producers Guild USA Kick off Film Production With Arrival of Annie Macaulay Idibia”.

- ^ “Nollywood USA emerging”. 8 June 2013.

- ^ Brown, DeNeen (23 May 2013). “Nollywood USA: African Movie Makers Expand Filming to D.C. Area”. The Washington Post.

- ^ “Stolen, a Nollywood-USA movie by Robert Peters”. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012.

- ^ Miller, Jade L. (3 June 2016). Nollywood Central: The Nigerian Videofilm Industry. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84457-694-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Husseini, Shaibu. “A YEAR OF MIXED FORTUNES FOR NOLLYWOOD”. Ehizoya Films. Ehizoya Golden Entertainment. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Olamide (31 December 2013). “Group Wants ‘Nollywood’ Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. yabaleftonline.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ “NOLLYWOODTUBE”. NOLLYWOODTUBE. 12 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Ekeanyanwu, Nnamdi Tobechukwu. “Nollywood, New Communication Technologies and Indigenous Cultures in a Globalized World: The NigerianDilemma”. Covenant University. Department of Mass Communication, College of Human Development. Retrieved 20 February 2015.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Angelo, Mike (30 November 2013). “Nollywood At 20: Organisers’ Flaws… Top Names Erased From Award List”. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ Tolu (1 January 2014). “Why ‘Nollywood’ Has to be Renamed to ‘Naiwood'”. Information Nigeria. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Bada, Gbenga. “Hon. Rotimi Makinde sparks off controversy over Nollywood @ 20 celebrations”. MOMO. Movie Moments. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ McCain, Carmen (30 July 2011). “NOLLYWOOD AND ITS TERMINOLOGY MIGRAINES”. NigeriaFilms.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nollywood New releases in 2021”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Oyeniya, Adegboyega (8 November 2013). “Nollywood at 20?”. The Punch Newspaper. The Punch NG. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Nigeria: October 1 Will Open New Chapter in My Life – Kunle Afolayan”. allAfrica.com. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.