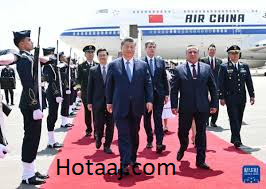

On the morning of November 23, 2024, President Xi Jinping returned to Beijing by special plane after a highly significant diplomatic tour. His trip included attending the 31st APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting, the 19th G20 Summit, and conducting state visits to Peru and Brazil. This international engagement underscored China’s active participation in global economic governance and its strengthening of bilateral relations with key Latin American countries.

Accompanying President Xi on the return journey were several high-ranking officials from the Chinese leadership, including Cai Qi, a member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and Director of the General Office of the CPC Central Committee, as well as Wang Yi, a member of the Political Bureau and Foreign Minister. Other members of the Chinese delegation also returned with the president on the same flight.

Prior to departure, after a brief technical stopover in Casablanca, Morocco, Moroccan Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch, along with other officials, extended their farewells at the airport. This marks the end of a diplomatic trip that reinforced China’s growing presence on the global stage and its commitment to multilateral cooperation in addressing economic challenges and promoting sustainable development.

On the morning of November 23, 2024, President Xi Jinping returned to Beijing by special plane, completing a significant diplomatic tour that spanned multiple continents. During the trip, he attended the 31st APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting and the 19th G20 Summit, two pivotal events in the global economic calendar. His travels also included state visits to Peru and Brazil, where he further strengthened China’s ties with Latin American countries and reinforced his commitment to deepening cooperation in trade, infrastructure, and political relations.

Throughout his time abroad, President Xi engaged in discussions on a wide range of global issues, from economic development to climate change, showcasing China’s role in addressing pressing global challenges. His participation in the APEC and G20 Summits underscored China’s dedication to multilateralism and international collaboration, positioning the country as a key player in shaping the future of global governance.

On board the return flight to Beijing were several high-ranking Chinese officials, including Cai Qi, a member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and Director of the General Office of the CPC Central Committee, and Wang Yi, the Foreign Minister of China. These officials were part of the entourage accompanying the president on his trip.

During a brief technical stopover in Casablanca, Morocco, the president was bid farewell by Moroccan Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch, who, along with other Moroccan officials, saw President Xi off at the airport. This stopover marked a brief pause in the president’s long journey back to China, adding a final diplomatic note to his extensive international tour.

The trip concluded with President Xi’s return to Beijing, where he is expected to continue his efforts to advance China’s diplomatic goals and economic initiatives in the aftermath of the successful meetings and state visits. The president’s engagements with global leaders, especially in the context of APEC and the G20, have reinforced China’s position as a central force in shaping the international economic and political landscape.

On the morning of November 23, 2024, Chinese President Xi Jinping returned to Beijing by special plane after a momentous and multifaceted diplomatic tour. Over the course of his trip, he participated in the 31st APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting and the 19th G20 Summit, two of the most influential international platforms for economic cooperation. In addition to these major multilateral meetings, President Xi conducted state visits to Peru and Brazil, marking another significant chapter in China’s expanding ties with Latin American countries.

At the APEC and G20 Summits, President Xi played a leading role in discussions aimed at addressing global economic challenges, including sustainable development, trade imbalances, and climate change. His presence underscored China’s commitment to shaping the future of international economic cooperation and its advocacy for a more inclusive global economy. During his state visits to Peru and Brazil, Xi strengthened bilateral relations through agreements in trade, infrastructure, and cultural exchange, reflecting China’s growing influence in Latin America and its support for the region’s development.

Accompanying President Xi on the return flight were several top Chinese officials, including Cai Qi, a key member of the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee and Director of the General Office of the CPC Central Committee, as well as Foreign Minister Wang Yi. They were part of the official entourage that had accompanied the president throughout his travels and participated in high-level discussions alongside him. These officials are integral to advancing China’s foreign policy and international outreach, and their presence on the return flight signifies the importance of the diplomatic mission.

Before departing, the president’s plane made a brief technical stopover in Casablanca, Morocco, where Moroccan Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch and other senior Moroccan officials were on hand to see him off. This gesture of farewell added a final diplomatic note to the trip, reinforcing the warm relations between China and Morocco.

The president’s return marks the conclusion of a highly successful diplomatic mission that has not only bolstered China’s standing in global economic affairs but also reinforced its strategic partnerships in Latin America and beyond. With the trip’s successful conclusion, President Xi is expected to continue to advocate for China’s vision of global governance, multilateral cooperation, and the promotion of peace and stability in the international order. The trip also sets the stage for future engagement with the countries and organizations he met, further strengthening China’s global diplomatic presence.

Courtesy: Brut India

References

- ^ “Association for Conversation of Hong Kong Indigenous Languages Online Dictionary”. hkilang.org. 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Wong 2023, p. 21.

- ^ “Profile: Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping”. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 7 November 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ^ 與丈夫習仲勛相伴58年 齊心: 這輩子無比幸福 [With her husband Xi Zhongxun for 58 years: very happy in this life] (in Traditional Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. 28 April 2009. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Chan, Alfred L. (24 March 2022). “Childhood and Youth: Privilege and Trauma, 1953–1979”. Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-761525-6. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ Takahashi, Tetsushi (1 June 2002). “Connecting the dots of the Hong Kong law and veneration of Xi”. Nikkei Shimbun. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Osnos, Evan (30 March 2015). “Born Red”. The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Li, Cheng. “Xi Jinping’s Inner Circle (Part 2: Friends from Xi’s Formative Years)” (PDF). Hoover Institution. pp. 6–22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Tisdall, Simon (29 December 2019). “The power behind the thrones: 10 political movers and shakers who will shape 2020”. The Guardian. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Wei, Lingling (27 February 2018). “Who Is ‘Uncle He?’ The Man in Charge of China’s Economy”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Bouée 2010, p. 93.

- ^ “习近平: “我坚信我的父亲是一个大英雄”” [Xi Jinping: “I firmly believe my father is a great hero”] (in Chinese). State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television. 14 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

女儿习和平…在”文化大革命”中被迫害致死, 是习仲勋难以抹去的心痛.

[His daughter Xi Heping… was persecuted to death during the “Cultural Revolution”, which is a heartache that Xi Zhongxun could not erase.] - ^ Buckley, Chris; Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (24 September 2015). “Cultural Revolution Shaped Xi Jinping, From Schoolboy to Survivor”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ shi, Z.C. (2017). 习近平的七年知青岁月 [Xi Jinping’s Seven Years as an Educated Youth] (in Chinese). China Central Party School Press. ISBN 978-7-5035-6163-4. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ 不忘初心: 是什么造就了今天的习主席? [What Were His Original Intentions? The President Xi of Today]. Youku (in Simplified Chinese). 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Page, Jeremy (23 December 2020). “How the U.S. Misread China’s Xi: Hoping for a Globalist, It Got an Autocrat”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ “《足迹》第1集:过”五关”有多难” [“Footprints” Episode 1: How difficult is it to pass the “Five Gates”]. Xinhua News Agency (in Chinese). 23 May 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ “习近平的七年知青岁月” [Xi Jinping’s Seven Years as an Educated Youth]. China News Service (in Chinese). 1 July 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ Lim, Louisa (9 November 2012). “For China’s Rising Leader, A Cave Was Once Home”. NPR. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ Demick, Barbara; Pierson, David (14 February 2012). “China’s political star Xi Jinping is a study in contrasts”. Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ Matt Rivers (19 March 2018). “This entire Chinese village is a shrine to Xi Jinping”. CNN. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b 習近平扶貧故事 [Xi Jinping’s Poverty Alleviation Story] (in Chinese). Sino United Electronic Publishing Limited. 2021. pp. 19–61. ISBN 978-988-8758-27-2. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ 中國報告—-習近平如何改變中國 [China Report—-How Xi Jinping is changing China]. China Interpretation Series (in Chinese). Flexible Cultural Enterprise Co., Ltd. 2014. p. 12. ISBN 978-986-5721-05-3. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ Chan, A.L. (2022). Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018. Oxford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-19-761522-5. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ “Xi Jinping 习近平” (PDF). Brookings Institution. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ Ranade, Jayadva (25 October 2010). “China’s Next Chairman – Xi Jinping”. Centre for Air Power Studies. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ^ Chan, A.L. (2022). Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-761522-5. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ 延川县志 [Yanchuan County Annals]. Shaanxi Local Chronicles Series (in Chinese). Shaanxi People’s Publishing House. 1999. p. 41. ISBN 978-7-224-05262-6. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ 红墙内的子女们 [Children Within the Red Wall] (in Chinese). Yanbian University Press. 1998. p. 468. ISBN 978-7-5634-1080-4. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ 缙麓别调(三) [Jinlu Special Tune (Part 3)] (in Chinese). Chongqing University Electronic Audiovisual Publishing House Co., Ltd. 2021. p. 76. ISBN 978-7-5689-2545-7. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ Pengpeng, Z. 谜一样的人生 [A Mysterious Life] (in Chinese). Zhu Peng Peng. p. 619. ISBN 978-0-9787999-2-2. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ Zhong, Wen; Zhang, Jie (2022). 习近平传 [Biography of Xi Jinping] (in Chinese). Metaverse Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-034-94892-6. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Simon & Cong 2009, pp. 28–29.

- ^ 耿飚传 [Biography of Geng Biao] (in Chinese). People’s Liberation Army Press. 2009. ISBN 978-7-5065-5904-1. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Guo, X. (2019). The Politics of the Core Leader in China: Culture, Institution, Legitimacy, and Power. Cambridge University Press. p. 363. ISBN 978-1-108-48049-9. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Li, C. (2016). Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership. Brookings Institution Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-8157-2694-4. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Johnson, Ian (30 September 2012). “Elite and Deft, Xi Aimed High Early in China”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b 精准扶贫的辩证法 [The Dialectics of Targeted Poverty Alleviation] (in Chinese). Xiamen University Press. 2018. p. 59. ISBN 978-7-5615-6916-0. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ “习近平同志当县委书记时就被认为是栋梁之才” [Comrade Xi Jinping was considered a pillar of talent when he was the county party secretary]. Xinhua News Agency (in Chinese). 8 February 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ 决战2020:拒绝贫困 [Decisive Battle of 2020: Say No to Poverty] (in Chinese). China Democracy and Legal System Publishing House. 2016. p. 12. ISBN 978-7-5162-1125-0. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b 正定縣志 [Zhengding Chronicle] (in Chinese). China City Press. 1992. pp. 73–548. ISBN 978-7-5074-0610-8. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ 青春岁月: 当代青年小报告文学选 [Youth Years: A Selection of Contemporary Youth Reportage] (in Chinese). People’s Literature Publishing House. 1986. p. 62. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b 河北社会主义核心价值观培育践行报告 [Hebei’s Report on the Cultivation and Practice of Socialist Core Values] (in Chinese). Social Sciences Literature Press. 2023. p. 3. ISBN 978-7-5228-1618-0. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ 紅色后代 [Red Offspring] (in Chinese). Chengdu Publishing House. 1996. p. 286. ISBN 978-7-80575-946-3. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ 血脉总相连: 中国名人后代大寻踪 [Blood is Always Connected: Tracing the Descendants of Chinese Celebrities] (in Chinese). Beijing Yanshan Publishing House. 1993. p. 363. ISBN 978-7-5402-0658-1. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ 河北青年 [Hebei Youth] (in Chinese). Hebei Youth Magazine. 1984. p. 5. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ 决策论 [Decision Theory] (in Chinese). Beijing Book Co. Inc. 2018. p. 141. ISBN 978-7-226-05307-2. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ 社会的逻辑 [The Logic of Society] (in Chinese). Peking University Press. 2017. p. 17. ISBN 978-7-301-26916-9. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “习近平与人民日报的10个故事” [10 stories about Xi Jinping and People’s Daily]. Haiwai Net (in Chinese). 15 June 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “中共元老何載逝世 曾薦習近平「棟樑之才」” [He Zai, the veteran of the CCP, passed away. He once recommended Xi Jinping as a “pillar of talent”]. China Times (in Chinese). 17 November 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ “104岁中共元老何载逝世 曾荐习近平”栋梁之才”” [He Zai, a 104-year-old CCP veteran, passed away. He once recommended Xi Jinping as a “pillar of talent”]. Sing Tao Daily (in Chinese). 16 November 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Aoyagi, W.S.A. (2017). History of Biodiesel – with Emphasis on Soy Biodiesel (1900-2017): Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook. Soyinfo Center. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-928914-97-6. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ “˭谁能想到石家庄食品协会主席成了中国领导人” [Who would have thought that the chairman of Shijiazhuang Food Association would become the Chinese leader?]. China National Radio (in Chinese). 23 September 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Zhang, Qizi (2016). 厦门城市治理体系和治理能力现代化研究 [Research on the modernization of Xiamen’s urban governance system and governance capacity]. A series of achievements of inter-academy cooperation of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: Xiamen (in Chinese). Social Sciences Literature Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-7-5097-9562-0. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ “白鹭振翅 向风而行” [Egrets flap their wings and fly into the wind]. Xinhua News Agency (in Chinese). 25 July 2024. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ “习近平同志推动厦门经济特区建设发展的探索与实践” [Comrade Xi Jinping’s exploration and practice in promoting the construction and development of Xiamen Special Economic Zone]. State Council of the People’s Republic of China (in Chinese). 26 May 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ “时政长镜头丨筼筜回响” [Long shot of current affairs丨Yuanlong Echo]. Science and Technology Daily (in Chinese). 21 February 2024. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Kuhn, R.L. (2011). How China’s Leaders Think: The Inside Story of China’s Past, Current and Future Leaders. Wiley. p. 420. ISBN 978-1-118-10425-5. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Dillon, M. (2021). China in the Age of Xi Jinping. Taylor & Francis. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-000-37096-6. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Brown, W.N. (2021). Chasing the Chinese Dream: Four Decades of Following China’s War on Poverty. Springer Nature Singapore. p. 9. ISBN 978-981-16-0654-0. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Brown, W.N. (2022). The Evolution of China’s Anti-Poverty Strategies: Cases of 20 Chinese Changing Lives. Springer Nature Singapore. p. 6. ISBN 978-981-19-7281-2. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ 中国脱贫攻坚精神 [China’s Spirit of Poverty Alleviation] (in Chinese). Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press. 2021. p. 74. ISBN 978-7-5680-6816-1. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Feng, Hexia (2023). 中国的贫困治理 [Poverty Governance in China] (in Chinese). Social Sciences Literature Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-7-5228-1509-1. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lam, W. (2023). Xi Jinping: The Hidden Agendas of China’s Ruler for Life. Taylor & Francis. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-000-92583-8. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Chan, A.L. (2022). Xi Jinping: Political Career, Governance, and Leadership, 1953-2018. Oxford University Press. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-19-761522-5. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ 《福州年鉴》编辑委员会 (1995). 福州年鉴 (in Chinese). 中国统计出版社. p. 16. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ Tiezzi, Shannon (4 November 2014). “From Fujian, China’s Xi Offers Economic Olive Branch to Taiwan”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ 驼铃: 大众文学 (in Chinese). 驼铃杂志社. 2000. p. 45. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ Ho, Louise (25 October 2012). “Xi Jinping’s time in Zhejiang: doing the business”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Chatwin, Jonathan (2024). The Southern Tour: Deng Xiaoping and the Fight for China’s Future. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781350435711.

- ^ Wang, Lei (25 December 2014). 习近平为官之道 拎着乌纱帽干事 [Xi Jinping’s Governmental Path – Carries Official Administrative Posts]. Duowei News (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Tian, Yew Lun; Chen, Laurie; Cash, Joe (11 March 2023). “Li Qiang, Xi confidant, takes reins as China’s premier”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ 习近平任上海市委书记 韩正不再代理市委书记 [Xi Jinping is Secretary of Shanghai Municipal Party Committee – Han Zheng is No Longer Acting Party Secretary]. Sohu (in Simplified Chinese). 24 March 2007. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ “China new leaders: Xi Jinping heads line-up for politburo”. BBC News. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ 从上海到北京 习近平贴身秘书只有钟绍军 [From Shanghai to Beijing, Zhong Shaojun Has Been Xi Jinping’s Only Personal Secretary]. Mingjing News (in Simplified Chinese). 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Lam 2015, p. 56.

- ^ 新晋政治局常委: 习近平 [Newly Appointed Member of Politburo Standing Committee: Xi Jinping]. Caijing (in Simplified Chinese). 22 October 2007. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ “Wen Jiabao re-elected China PM”. Al Jazeera. 16 March 2008. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ “Vice-President Xi Jinping to Visit DPRK, Mongolia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Yemen”. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 5 June 2008. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Wines, Michael (9 March 2009). “China’s Leaders See a Calendar Full of Anniversaries, and Trouble”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 July 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Anderlini, Jamil (20 July 2012). “Bo Xilai: power, death and politics”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Palmer, James (19 October 2017). “The Resistible Rise of Xi Jinping”. Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 6 February 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Ansfield, Jonathan (22 December 2007). “Xi Jinping: China’s New Boss And The ‘L’ Word”. Newsweek. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Elegant, Simon (19 November 2007). “China’s Nelson Mandela”. Time. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Elegant, Simon (15 March 2008). “China Appoints Xi Vice President, Heir Apparent to Hu”. Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Uren, David (5 October 2012). “Rudd seeks to pre-empt PM’s China white paper with his own version”. The Australian. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Chinese VP Receives Key to the City of Montego Bay”. Jamaica Information Service. 15 February 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ “Chinese VP praises friendly cooperation with Venezuela, Latin America”. CCTV. Xinhua. 18 February 2009. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ “Xi Jinping proposes efforts to boost cooperation with Brazil”. China Daily. 20 February 2009. Archived from the original on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ “Chinese vice president begins official visit”. Times of Malta. 22 February 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Sim, Chi Yin (14 February 2009). “Chinese VP blasts meddlesome foreigners”. AsiaOne. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Lai, Jinhong (18 February 2009). 習近平出訪罵老外 外交部捏冷汗 [Xi Jinping Goes and Scolds at Foreigners, Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Cold Sweat]. United Daily News (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ “A Journey of Friendship, Cooperation and Culture – Vice Foreign Minister Zhang Zhijun Sums Up Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping’s Trip to 5 European Countries”. Permanent Representative of China to the United Nations. 21 October 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Raman, B. (25 December 2009). “China’s Cousin-Cousin Relations with Myanmar”. South Asia Analysis Group. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Bull, Alister; Chris Buckley (24 January 2012). “China leader-in-waiting Xi to visit White House next month”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Kirk (15 February 2012). “Xi Jinping of China Makes a Return Trip to Iowa”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Beech, Hannah (15 September 2012). “China’s Heir Apparent Xi Jinping Reappears in Public After a Two-Week Absence”. Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “China Confirms Leadership Change”. BBC News. 17 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ “Xi Jinping: China’s ‘princeling’ new leader”. Hindustan Times. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Wong, Edward (14 November 2012). “Ending Congress, China Presents New Leadership Headed by Xi Jinping”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ FlorCruz, Jaime A; Mullen, Jethro (16 November 2012). “After months of mystery, China unveils new top leaders”. CNN. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Ian (15 November 2012). “A Promise to Tackle China’s Problems, but Few Hints of a Shift in Path”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ “Full text: China’s new party chief Xi Jinping’s speech”. BBC News. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Page, Jeremy (13 March 2013). “New Beijing Leader’s ‘China Dream'”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Chen, Zhuang (10 December 2012). “The symbolism of Xi Jinping’s trip south”. BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Demick, Barbara (3 March 2013). “China’s Xi Jinping formally assumes title of president”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Cheung, Tony; Ho, Jolie (17 March 2013). “CY Leung to meet Xi Jinping in Beijing and explain cross-border policies”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ “China names Xi Jinping as new president”. Inquirer.net. Agence France-Presse. 15 March 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ People’s Daily, Department of Commentary (20 November 2019). “Stories of Incorrupt Government: “The Corruption and Unjustness of Officials Give Birth to the Decline of Governance””. Narrating China’s Governance. Singapore: Springer Singapore. pp. 3–39. doi:10.1007/978-981-32-9178-2_1. ISBN 978-981-329-177-5.

- ^ “Xi Jinping’s inaugural Speech”. BBC News. 15 November 2012. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew (27 March 2013). “Elite in China Face Austerity Under Xi’s Rule”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Oster, Shai (4 March 2014). “President Xi’s Anti-Corruption Campaign Biggest Since Mao”. Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Heilmann 2017, pp. 62–75.

- ^ “China’s Soft-Power Deficit Widens as Xi Tightens Screws Over Ideology”. Brookings Institution. 5 December 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ “Charting China’s ‘great purge’ under Xi”. BBC News. 22 October 2017. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ “Tiger in the net”. The Economist. 11 December 2014. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ^ “China’s former military chief of staff jailed for life for corruption”. The Guardian. 20 February 2019. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ “China’s anti-corruption campaign expands with new agency”. BBC News. 20 March 2018. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “31个省级纪委改革方案获批复 12省已完成纪委”重建”” [31 Provincial Commission for Discipline Inspection Reform Plans Approved 12 Provinces Have Completed “Reconstruction”]. Xinhua News Agency. 13 June 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Chin, Josh (15 December 2021). “Xi Jinping’s Leadership Style: Micromanagement That Leaves Underlings Scrambling”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Wong, Chun Han (16 October 2022). “Xi Jinping’s Quest for Control Over China Targets Even Old Friends”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “China re-connects: joining a deep-rooted past to a new world order”. Jesus College, Cambridge. 19 March 2021. Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Wang, Gungwu (7 September 2019). “Ancient past, modern ambitions: historian Wang Gungwu’s new book on China’s delicate balance”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Denyer, Simon (25 October 2017). “China’s Xi Jinping unveils his top party leaders, with no successor in sight”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

Censorship has been significantly stepped up in China since Xi took power.

- ^ Economy, Elizabeth (29 June 2018). “The great firewall of China: Xi Jinping’s internet shutdown”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

Before Xi Jinping, the internet was becoming a more vibrant political space for Chinese citizens. But today the country has the largest and most sophisticated online censorship operation in the world.

- ^ “Xi outlines blueprint to develop China’s strength in cyberspace”. Xinhua News Agency. 21 April 2018. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Zhuang, Pinghui (19 February 2016). “China’s top party mouthpieces pledge ‘absolute loyalty’ as president makes rare visits to newsrooms”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Risen, Tom (3 June 2014). “Tiananmen Censorship Reflects Crackdown Under Xi Jinping”. U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Bougon 2018, pp. 157–65.

- ^ Tiezzi, Shannon (24 June 2014). “China’s ‘Sovereign Internet'”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ Ford, Peter (18 December 2015). “On Internet freedoms, China tells the world, ‘leave us alone'”. The Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ “Wikipedia blocked in China in all languages”. BBC News. 14 May 2019. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (6 August 2015). “‘It’s getting worse’: China’s liberal academics fear growing censorship”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Grigg, Angus (4 July 2015). “How China stopped its bloggers”. The Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ “China Tells Carriers to Block Access to Personal VPNs by February”. Bloomberg News. 10 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Phillips, Tom (24 October 2017). “Xi Jinping becomes most powerful leader since Mao with China’s change to constitution”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ “China elevates Xi to most powerful leader in decades”. CBC News. 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ “China elevates Xi Jinping’s status, making him the most powerful leader since Mao”. Irish Independent. 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Collins, Stephen (9 November 2017). “Xi’s up, Trump is down, but it may not matter”. CNN. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Holtz, Michael (28 February 2018). “Xi for life? China turns its back on collective leadership”. The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Andrésy, Agnès (2015). Xi Jinping: Red China, The Next Generation. UPA. p. 88. ISBN 9780761866015. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Pollard, Martin (26 October 2022). “China’s Xi deals knockout blow to once-powerful Youth League faction”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ Gan, Nectar (23 September 2017). “Latest Xi Jinping book gives clues on decline of Communist Party’s youth wing”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Shi, Jiangtao; Huang, Kristin (26 February 2018). “End to term limits at top ‘may be start of global backlash for China'”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (4 March 2018). “Xi Jinping’s power play: from president to China’s new dictator?”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Wen, Philip (17 March 2018). “China’s parliament re-elects Xi Jinping as president”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Bodeen, Christopher (17 March 2018). “Xi reappointed as China’s president with no term limits”. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Zhou, Xin (18 March 2018). “Li Keqiang endorsed as China’s premier; military leaders confirmed”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, Tom (7 September 2019). “China’s Xi Jinping says he is opposed to life-long rule”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

President insists term extension is necessary to align government and party posts

- ^ Wang, Cat (7 November 2021). “The significance of Xi Jinping’s upcoming ‘historical resolution'”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Ni, Vincent (11 November 2021). “Chinese Communist party elevates Xi’s status in ‘historical resolution'”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Wong, Chun Han; Zhai, Keith (17 November 2021). “How Xi Jinping Is Rewriting China’s History to Put Himself at the Center”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Bandurski, David (8 February 2022). “Two Establishes”. China Media Project. Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Davidson, Helen; Graham-Harrison, Emma (23 October 2022). “China’s leader Xi Jinping secures third term and stacks inner circle with loyalists”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ Wingfield-Hayes, Rupert (23 October 2022). “Xi Jinping’s party is just getting started”. BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ “Shake-up at the top of China’s Communist Party as Xi Jinping starts new term”. South China Morning Post. 22 October 2022. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

- ^ “Xi Jinping unanimously elected Chinese president, PRC CMC chairman”. Xinhua News Agency. 10 March 2023. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ “The power of Xi Jinping”. The Economist. 18 September 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Jiayang, Fan; Taisu, Zhang; Ying, Zhu (8 March 2016). “Behind the Personality Cult of Xi Jinping”. Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Phillips, Tom (19 September 2015). “Xi Jinping: Does China truly love ‘Big Daddy Xi’ – or fear him?”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 27 April 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Blanchard, Ben (28 October 2016). “All hail the mighty uncle – Chinese welcome Xi as the ‘core'”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ “Xi’s Nickname Becomes Out of Bounds for China’s Media”. Bloomberg News. 28 April 2015. Archived from the original on 12 October 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Rivers, Matt (19 March 2018). “This entire Chinese village is a shrine to Xi Jinping”. CNN. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Gan, Nectar (28 December 2017). “Why China is reviving Mao’s grandiose title for Xi Jinping”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ “Xi Jinping is no longer any old leader”. The Economist. 17 February 2018. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Shepherd, Christian; Wen, Philip (20 October 2017). “With tears and song, China welcomes Xi as great, wise leader”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Qian, Gang (2 November 2020). “A Brief History of the Helmsmen”. China Media Project. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- ^ Nakazawa, Katsuji (9 January 2020). “China crowns Xi with special title, citing rare crisis”. Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Whyte, Martin K. (15 March 2021). “China’s economic development history and Xi Jinping’s “China dream:” an overview with personal reflections”. Chinese Sociological Review. 53 (2): 115–134. doi:10.1080/21620555.2020.1833321. ISSN 2162-0555. S2CID 228867589.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Kroeber, Arthur R. (17 November 2013). “Xi Jinping’s Ambitious Agenda for Economic Reform in China”. Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ Denyer, Simon (25 August 2013). “Creeping reforms as China gives Shanghai Free Trade Zone go-ahead”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 3 June 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ Buckley, Chris; Bradsher, Keith (4 March 2017). “Xi Jinping’s Failed Promises Dim Hopes for Economic Change in 2nd Term”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Wong 2023, p. 146.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Orlik, Tom; Hancock, Tom (3 March 2023). “What Wall Street Gets Wrong About Xi Jinping’s New Money Men”. Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ Wang, Orange; Leng, Sidney (28 September 2018). “Chinese President Xi Jinping’s show of support for state-owned firms ‘no surprise’, analysts say”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Gan, Nectar (28 September 2018). “Xi says it’s wrong to ‘bad mouth’ China’s state firms… but country needs private sector as well”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Pieke & Hofman 2022, p. 48.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lockett, Hudson (12 June 2022). “How Xi Jinping is reshaping China’s capital markets”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (4 March 2017). “China and Economic Reform: Xi Jinping’s Track Record”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Wildau, Gabriel (18 December 2018). “Xi says no one can ‘dictate to the Chinese people'”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ “Xi Puts His Personal Stamp on China’s Fight Against Poverty”. Bloomberg News. 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ “China’s Xi declares victory in ending extreme poverty”. BBC News. 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ “China’s poverty line is not as stingy as commentators think”. The Economist. Hong Kong. 18 June 2020. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ “World Bank Open Data”. Archived from the original on 14 April 2024. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ “GDP (current US$) – China | Data”. World Bank. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ “World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023”. International Monetary Fund. April 2023. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ “GDP growth (annual %) – China | Data”. World Bank. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Hui, Mary (16 February 2022). “What China means when it says it wants “high quality” GDP growth”. Quartz. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Marquis, Christopher; Qiao, Kunyuan (2022). Mao and Markets: The Communist Roots of Chinese Enterprise. Kunyuan Qiao. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-26883-6. OCLC 1348572572.

- ^ Wei, Lingling (12 August 2020). “China’s Xi Speeds Up Inward Economic Shift”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ “China’s future economic potential hinges on its productivity”. The Economist. 14 August 2021. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ “China’s Escalating Property Curbs Point to Xi’s New Priority”. Bloomberg News. 27 July 2021. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ “Housing Should Be for Living In, Not for Speculation, Xi Says”. Bloomberg News. 18 October 2017. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Lin, Andy; Hale, Thomas; Hudson, Hudson (8 October 2021). “Half of China’s top developers crossed Beijing’s ‘red lines'”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Wei, Lingling (19 October 2021). “In Tackling China’s Real-Estate Bubble, Xi Jinping Faces Resistance to Property-Tax Plan”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Tran, Hung (14 March 2023). “China’s debt-reduction campaign is making progress, but at a cost”. Atlantic Council. Archived from the original on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Fifield, Anna (2 November 2018). “As China settles in for trade war, leader Xi emphasizes ‘self reliance'”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Han, Chen; Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany (15 October 2022). “What China looks like after a decade of Xi Jinping’s rule”. Axios. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ Yap, Chuin-Wei (25 December 2019). “State Support Helped Fuel Huawei’s Global Rise”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ “Xinhua Commentary: “New productive forces” a winning formula for China’s future”. Xinhuanet. 21 September 2023.

- ^ “Xiongan is Xi Jinping’s pet project”. The Economist. 18 May 2023. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Full Text: Xi Jinping’s Speech on Boosting Common Prosperity – Caixin Global”. Caixin Global. 19 October 2021. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Wei, Jing Yang and Lingling (12 November 2020). “China’s President Xi Jinping Personally Scuttled Jack Ma’s Ant IPO”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Hass, Ryan (9 September 2021). “Assessing China’s “common prosperity” campaign”. Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Shen, Samuel; Ranganathan, Vidya (3 November 2021). “China stock pickers reshape portfolios on Xi’s ‘common prosperity'”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Moore, Elena (10 April 2021). “China Fines Alibaba $2.8 Billion For Breaking Anti-Monopoly Law”. NPR. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ “China’s Education Crackdown Pushes Costly Tutors Underground”. Bloomberg News. 12 August 2021. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ “Trading kicks off on Beijing Stock Exchange, 10 stocks surge”. Reuters. 15 November 2021. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Stevenson, Alexandra; Chien, Amy Chang; Li, Cao (27 August 2021). “China’s Celebrity Culture Is Raucous. The Authorities Want to Change That”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Buckley, Chris (30 August 2021). “China Tightens Limits for Young Online Gamers and Bans School Night Play”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Wuthnow, Joel (30 June 2016). “China’s Much-Heralded NSC Has Disappeared”. Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Lampton, David M. (3 September 2015). “Xi Jinping and the National Security Commission: policy coordination and political power”. Journal of Contemporary China. 24 (95): 759–777. doi:10.1080/10670564.2015.1013366. ISSN 1067-0564. S2CID 154685098.

- ^ Jun, Mai (21 March 2018). “China unveils bold overhaul to tighten Communist Party control”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Keck, Zachary (7 January 2014). “Is Li Keqiang Being Marginalized?”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Sridahan, Vasudevan (27 December 2015). “China formally abolishes decades-old one-child policy”. International Business Times. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Wee, Sui-Lee (31 May 2021). “China Says It Will Allow Couples to Have 3 Children, Up From 2”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (21 July 2021). “China scraps fines, will let families have as many children as they’d like”. CNBC. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ “Li Keqiang: China’s marginalised premier”. BBC News. 28 September 2020. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Wei, Lingling (11 May 2022). “China’s Forgotten Premier Steps Out of Xi’s Shadow as Economic Fixer”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Attrill, Nathan; Fritz, Audrey (24 November 2021). “China’s cyber vision: How the Cyberspace Administration of China is building a new consensus on global internet governance” (PDF). Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Chen, Laurie; Tang, Ziyi (16 March 2023). “China to create powerful financial watchdog run by Communist Party”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Mitchell, Tom (25 July 2016). “Xi’s China: The rise of party politics”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Buckley, Chris (21 March 2018). “China Gives Communist Party More Control Over Policy and Media”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ^ Hao, Mingsong; Ke, Xiwang (5 July 2023). “Personal Networks and Grassroots Election Participation in China: Findings from the Chinese General Social Survey”. Journal of Chinese Political Science. 29 (1): 159–184. doi:10.1007/s11366-023-09861-3. ISSN 1080-6954.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Wong, Chun Han; Zhai, Keith (16 March 2023). “China’s Communist Party Overhaul Deepens Control Over Finance, Technology”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ “China Overhauls Financial Regulatory Regime to Control Risks”. Bloomberg News. 7 March 2023. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith; Che, Chang (10 March 2023). “Why China Is Tightening Its Oversight of Banking and Tech”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- ^ “China passes law granting Communist Party more control over cabinet”. Reuters. 11 March 2024. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ “习近平出席中央全面依法治国工作会议并发表重要讲话”. Chinadaily.com.cn. 18 November 2020. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ Zhou, Laura; Huang, Cary (24 October 2014). “Communist Party pledges greater role for constitution, rights in fourth plenum”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Doyon, Jerome; Winckler, Hugo (20 November 2014). “The Fourth Plenum, Party Officials and Local Courts”. Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lague, David; Lim, Benjamin Kang (23 April 2019). “How China is replacing America as Asia’s military titan”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Bitzinger, Richard A. (2021). “China’s Shift from Civil-Military Integration to Military-Civil Fusion”. Asia Policy. 28 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1353/asp.2021.0001. ISSN 1559-2960. S2CID 234121234.

- ^ B. Kania, Elsa; Laskai, Lorand (28 January 2021). “Myths and Realities of China’s Military-Civil Fusion Strategy”. Center for a New American Security. JSTOR resrep28654. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Fifield, Anna (29 September 2019). “China’s Communist Party has one more reason to celebrate – a year longer in power than the U.S.S.R.” The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Meng, Chuan (4 November 2014). 习近平军中”亮剑” 新古田会议一箭多雕 [Xi Jinping And Central Army’s New “Bright Sword” Conference In Gutian Killed Many Birds With Only A Single Stone]. Duowei News (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Grammaticas, Damian (14 March 2013). “President Xi Jinping: A man with a dream”. BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Wong, Edward; Perlez, Jane; Buckley, Chris (2 September 2015). “China Announces Cuts of 300,000 Troops at Military Parade Showing Its Might”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 September 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Tiezzi, Shannon (2 February 2016). “It’s Official: China’s Military Has 5 New Theater Commands”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Kania, Elsa (18 February 2017). “China’s Strategic Support Force: A Force for Innovation?”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Blanchard, Ben (14 September 2016). “China sets up new logistics force as part of military reforms”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Wuthnow, Joel (16 April 2019). China’s Other Army: The People’s Armed Police in an Era of Reform (PDF). Washington: Institute for National Strategic Studies. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ “Xi Jinping named as ‘commander in chief’ by Chinese state media”. The Guardian. 21 April 2016. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Kayleigh, Lewis (23 April 2016). “Chinese President Xi Jinping named as military’s ‘commander-in-chief'”. The Independent. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Sison, Desiree (22 April 2016). “President Xi Jinping is New Commander-in-Chief of the Military”. China Topix. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ “China’s Xi moves to take more direct command over military”. Columbia Daily Tribune. 24 April 2016. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Buckley, Chris; Myers, Steven Lee (11 October 2017). “Xi Jinping Presses Military Overhaul, and Two Generals Disappear”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ He, Laura; McCarthy, Simone; Chang, Wayne (7 March 2023). “China to increase defense spending 7.2%, sets economic growth target of ‘around 5%’ for 2023”. CNN. Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ Miura, Kacie. “The Domestic Sources of China’s Maritime Assertiveness Under Xi Jinping” (PDF). Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ Lague, David; Kang Lim, Benjamin (30 April 2019). “China’s vast fleet is tipping the balance in the Pacific”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ Sun, Degang; Zoubir, Yahia H. (4 July 2021). “Securing China’s ‘Latent Power’: The Dragon’s Anchorage in Djibouti”. Journal of Contemporary China. 30 (130): 677–692. doi:10.1080/10670564.2020.1852734. ISSN 1067-0564. S2CID 229393446.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew; Perlez, Jane (25 February 2017). “U.S. Wary of Its New Neighbor in Djibouti: A Chinese Naval Base”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ “Xi Jinping has nurtured an ugly form of Chinese nationalism”. The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Meng, Angela (6 September 2014). “Xi Jinping rules out Western-style political reform for China”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Buckley, Chris (26 February 2018). “Xi Jinping Thought Explained: A New Ideology for a New Era”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Barrass, Gordon; Inkster, Nigel (2 January 2018). “Xi Jinping: The Strategist Behind the Dream”. Survival. 60 (1): 41–68. doi:10.1080/00396338.2018.1427363. ISSN 0039-6338. S2CID 158856300. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Zhao, Suisheng (2023). The Dragon Roars Back: Transformational Leaders and Dynamics of Chinese Foreign Policy. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 86. doi:10.1515/9781503634152. ISBN 978-1-5036-3088-8. OCLC 1331741429.

- ^ “Xi’s Vow of World Dominance by 2049 Sends Chill Through Markets”. Bloomberg News. 26 October 2022. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Hu, Weixing (2 January 2019). “Xi Jinping’s ‘Major Country Diplomacy’: The Role of Leadership in Foreign Policy Transformation”. Journal of Contemporary China. 28 (115): 1–14. doi:10.1080/10670564.2018.1497904. ISSN 1067-0564. S2CID 158345991. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Auto, Hermes (5 April 2021). “China’s ‘wolf warrior’ diplomats back to howl at Xinjiang critics”. The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Bishop, Bill (8 March 2019). “Xi’s thought on diplomacy is “epoch-making””. Axios. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Buckley, Chris (3 March 2021). “‘The East Is Rising’: Xi Maps Out China’s Post-Covid Ascent”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ Zhang, Denghua (May 2018). “The Concept of ‘Community of Common Destiny’ in China’s Diplomacy: Meaning, Motives and Implications”. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies. 5 (2): 196–207. doi:10.1002/app5.231. hdl:1885/255057. ISSN 2050-2680.

- ^ Tobin, Liza (2018). “Xi’s Vision for Transforming Global Governance: A Strategic Challenge for Washington and Its Allies (November 2018)”. Texas National Security Review. The University Of Texas At Austin, The University Of Texas At Austin. doi:10.26153/TSW/863. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Seib, Gerald F. (15 July 2022). “Putin and Xi’s Bet on the Global South”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Jones, Hugo (24 November 2021). “China’s Quest for Greater ‘Discourse Power'”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ “Telling China’s Story Well”. China Media Project. 16 April 2021. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Kynge, James; Hornby, Lucy; Anderlini, Jamil (26 October 2017). “Inside China’s secret ‘magic weapon’ for worldwide influence”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ “China’s Global Development Initiative is not as innocent as it sounds”. The Economist. 9 June 2022. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ Yao, Kevin; Tian, Yew Lun (22 April 2022). “China’s Xi proposes ‘global security initiative’, without giving details”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Cai, Jane (12 June 2023). “How China’s Xi Jinping promotes mix of Marxism and traditional culture to further Communist Party and ‘Chinese dream'”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 12 June 2023. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Tsang, Steve; Cheung, Olivia (2024). The Political Thought of Xi Jinping. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197689363.

- ^ “Xi Sees Threats to China’s Security Everywhere Heading Into 2021”. Bloomberg News. 30 December 2020. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Shinn, David H.; Eisenman, Joshua (2023). China’s Relations with Africa: a New Era of Strategic Engagement. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-21001-0.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Buckley, Chris; Myers, Steven Lee (6 August 2022). “In Turbulent Times, Xi Builds a Security Fortress for China, and Himself”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ “China passes counter-espionage law”. Reuters. 1 November 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Wong, Chun Han (1 July 2015). “China Adopts Sweeping National-Security Law”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Blanchard, Ben (28 December 2015). “China passes controversial counter-terrorism law”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Wagner, Jack (1 June 2017). “China’s Cybersecurity Law: What You Need to Know”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Wong, Edward (28 April 2015). “Clampdown in China Restricts 7,000 Foreign Organizations”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ “China passes tough new intelligence law”. Reuters. 27 June 2017. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Haldane, Matt (1 September 2021). “What China’s new data laws are and their impact on Big Tech”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Mozur, Paul; Xiao, Muyi; Liu, John (26 June 2022). “‘An Invisible Cage’: How China Is Policing the Future”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bland, Ben (2 September 2018). “Greater Bay Area: Xi Jinping’s other grand plan”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Young Hong Kongers Who Defied Xi Are Now Partying in China”. Bloomberg. 3 March 2024. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024.

- ^ Yu, Verna (5 November 2019). “China signals desire to bring Hong Kong under tighter control”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Buckley, Chris; Wang, Vivian; Ramzy, Austin (28 June 2021). “Crossing the Red Line: Behind China’s Takeover of Hong Kong”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Buckley, Chris; Forsythe, Michael (31 August 2014). “China Restricts Voting Reforms for Hong Kong”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Chan, Wilfred (19 June 2015). “Hong Kong legislators reject China-backed reform bill”. CNN. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Cheng, Kris (7 February 2017). “Carrie Lam is the only leadership contender Beijing supports, state leader Zhang Dejiang reportedly says”. Hong Kong Free Press. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Sin, Noah; Kwok, Donny (16 December 2019). “China’s Xi vows support for Hong Kong leader during ‘most difficult’ time”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Zhou, Laura (14 November 2019). “Xi Jinping again backs Hong Kong police use of force in stopping unrest”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ “China’s Xi warns of ‘foreign forces’ at Macao anniversary”. Deutsche Welle. 20 December 2019. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Siu, Phila; Cheung, Gary (19 December 2019). “Xi Jinping seen as indirectly lecturing Hong Kong as he tells Macau residents to make ‘positive voices’ heard and resolve problems with rationality”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Yip, Martin; Fraser, Simon (30 June 2022). “China’s President Xi arrives in Hong Kong for handover anniversary”. BBC News. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Ioanes, Ellen (2 July 2022). “Xi Jinping asserts his power on Hong Kong’s handover anniversary”. Vox. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Chan, Ho-him; Riordan, Primrose (8 May 2022). “Beijing-backed hardliner John Lee chosen as Hong Kong’s next leader”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Perlez, Jane; Ramzy, Austin (4 November 2015). “China, Taiwan and a Meeting After 66 Years”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ “One-minute handshake marks historic meeting between Xi Jinping and Ma Ying-jeou”. The Straits Times. 7 November 2015. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ^ Huang, Kristin (15 June 2021). “Timeline: Taiwan’s relations with mainland China under Tsai Ing-wen”. South China Morning Post. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bush, Richard C. (19 October 2017). “What Xi Jinping said about Taiwan at the 19th Party Congress”. Brookings Institution. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ Kuo, Lily (2 January 2019). “‘All necessary means’: Xi Jinping reserves right to use force against Taiwan”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Griffiths, James (2 January 2019). “Xi warns Taiwan independence is ‘a dead end'”. CNN. Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Lee, Yimou (2 January 2019). “Taiwan president defiant after China calls for reunification”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ “China: Events of 2017”. World Report 2018: Rights Trends in China. Human Rights Watch. 9 January 2018. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Withnall, Adam (17 January 2019). “Repression in China at worst level since Tiananmen Square, HRW warns”. The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ “China widens crackdown against grassroot activists”. Financial Times. 9 May 2019. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Sudworth, John (22 May 2017). “Wang Quanzhang: The lawyer who simply vanished”. BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ “Chinese dream turns sour for activists under Xi Jinping”. Bangkok Post. 10 July 2014. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gan, Nectar (14 November 2017). “Replace pictures of Jesus with Xi to escape poverty, Chinese villagers urged”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Denyer, Simon (14 November 2017). “Jesus won’t save you – President Xi Jinping will, Chinese Christians told”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Haas, Benjamin (28 September 2018). “‘We are scared, but we have Jesus’: China and its war on Christianity”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Bodeen, Christopher (10 September 2018). “Group: Officials destroying crosses, burning bibles in China”. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ Lau, Mimi (5 December 2019). “From Xinjiang to Ningxia, China’s ethnic groups face end to affirmative action in education, taxes, policing”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Zhai, Keith (8 October 2021). “China’s Communist Party Formally Embraces Assimilationist Approach to Ethnic Minorities”. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Linda, Lew (19 December 2020). “China puts Han official in charge of ethnic minority affairs as Beijing steps up push for integration”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Aaron, Glasserman (2 March 2023). “China’s Head of Ethnic Affairs Is Keen to End Minority Culture”. Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 12 March 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ^ “Xi Focus: Xi stresses high-quality development of Party’s work on ethnic affairs”. Xinhua News Agency. 28 August 2021. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Khatchadourian, Raffi (5 April 2021). “Surviving the Crackdown in Xinjiang”. The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Shepherd, Christian (12 September 2019). “Fear and oppression in Xinjiang: China’s war on Uighur culture”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Ramzy, Austin; Buckley, Chris (16 November 2019). “‘Absolutely No Mercy’: Leaked Files Expose How China Organized Mass Detentions of Muslims”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ “China cuts Uighur births with IUDs, abortion, sterilization”. Associated Press. 28 June 2020. Archived from the original on 16 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ “More than 20 ambassadors condemn China’s treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang”. The Guardian. 11 July 2019. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ “China’s Xi responsible for Uyghur ‘genocide’, unofficial tribunal says”. Reuters. 10 December 2021. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ “U.N. says China may have committed crimes against humanity in Xinjiang”. Reuters. 1 September 2022. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Tugendhat, Tom (19 January 2020). “Huawei’s human rights record needs scrutiny before Britain signs 5G contracts”. Hong Kong Free Press. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Even in secret, China’s leaders speak in code”. The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Chin, Josh (30 November 2021). “Leaked Documents Detail Xi Jinping’s Extensive Role in Xinjiang Crackdown”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Momen Langka! Presiden China Xi Jinping Kunjungi Kampung Muslim Uighur, Kompas TV, 19 July 2022, archived from the original on 7 March 2024, retrieved 7 March 2024 – via Youtube,

Selama 4 hari, Xi Jinping mengunjungi sejumlah situs di Xinjiang termasuk perkebunan kapas, zona perdagangan dan museum. Penduduk Uighur pun menyambut Presiden Xi Jinping. Dalam kunjungannya, Xi mendesak agar pejabat Xinjiang selalu mendengarkan suara rakyat demi memenangkan hati dan membuat rakyat bersatu.

- ^ China’s President Xi visits far western Xinjiang region for first time in 8 years, SCMP, 15 July 2022, archived from the original on 7 March 2024, retrieved 7 March 2024 – via Youtube

- ^ “Xi Jinping visits Xinjiang for first time since crackdown”. Deutsche Welle. 15 July 2022.

- ^ ONG HAN SEAN (20 November 2023). “China’s Xinjiang: A marvel of wild beauty and a land full of culture and charm”. The Star. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023.

Our visit came on the heels of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Ürümqi, where he reportedly stressed on the positive promotion of the region to show an open and confident Xinjiang. Xi also called for Xinjiang to be opened more widely for tourism to encourage visits from domestic and foreign tourists.

- ^ “China: How is Beijing whitewashing its Xinjiang policy?”. Deutsche Welle. 11 September 2023. Archived from the original on 7 March 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

But amid growing global attention on Xinjiang, China has been eager to portray the region as a “success story” by welcoming more tourists. In a speech that he made while visiting the region last month, Xi said Xinjiang was “no longer a remote area” and should open up more to domestic and foreign tourism.

- ^ Griffiths, James (17 February 2020). “Did Xi Jinping know about the coronavirus outbreak earlier than first suggested?”. CNN. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Page, Jeremy (27 January 2020). “China’s Xi Gives His No. 2 a Rare Chance to Shine in Coronavirus Fight, With Risks for Both”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Griffiths, James (24 January 2020). “Wuhan is the latest crisis to face China’s Xi, and it’s exposing major flaws in his model of control”. CNN. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Steger, Isabella (10 February 2020). “Xi Jinping emerges to meet the people for the first time in China’s coronavirus outbreak”. Quartz. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ “WHO dementiert Telefongespräch mit Chinas Präsident”. Der Spiegel (in German). 10 May 2020. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Yew, Lun Tian; Se, Young Lee (10 March 2022). “Xi visits Wuhan, signaling tide turning in China’s coronavirus battle”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Cao, Desheng. “Xi: Dynamic zero-COVID policy works”. China Daily. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wong, Chun Han (25 July 2022). “China’s Zero-Covid Policy Drags on Vaccination Drive”. The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (10 June 2022). “Xi Jinping says ‘persistence is victory’ as Covid restrictions return to Shanghai and Beijing”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 July 2024. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Hadano, Tsukasa; Doi, Noriyuki (29 June 2022). “Xi ally Li Qiang keeps Shanghai party chief job, but star fades”. Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ Cai, Jane; Tang, Frank (29 June 2022). “China to press on with ‘zero Covid’, despite economic risks: Xi”. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ “Covid in China: Xi Jinping and other leaders given domestic vaccine”. BBC News. 23 July 2022. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ McDonell, Stephen (16 October 2022). “Xi Jinping speech: Zero-Covid and zero solutions”. BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ “Xi Jinping tied himself to zero-Covid. Now he keeps silent as it falls apart”. CNN. 17 December 2022. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ Ramzy, Austin (11 November 2022). “China Eases Zero-Covid Rules as Economic Toll and Frustrations Mount”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Che, Chang; Buckley, Chris; Chien, Amy Chang; Dong, Joy (5 December 2022). “China Stems Wave of Protest, but Ripples of Resistance Remain”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Olcott, Eleanor; Mitchell, Tom (4 December 2022). “Chinese cities ease Covid restrictions following nationwide protests”. Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Che, Chang; Chien, Amy Chang; Stevenson, Alexandra (7 December 2022). “What Has Changed About China’s ‘Zero Covid’ Policy”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Li, David Daokui (2024). China’s World View: Demystifying China to Prevent Global Conflict. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393292398.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “China going carbon neutral before 2060 would lower warming projections by around 0.2 to 0.3 degrees C”. Climate Action Tracker. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ “China, the world’s top global emitter, aims to go carbon-neutral by 2060”. ABC News. 23 September 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ “China’s top climate scientists unveil road map to 2060 goal”. The Japan Times. Bloomberg News. 29 September 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ Brant, Robin (22 September 2021). “China pledges to stop building new coal energy plants abroad”. BBC News. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Faulconbridge, Guy (15 October 2021). “China’s Xi will not attend COP26 in person, UK PM Johnson told”. Reuters. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (10 November 2021). “China’s top Cop26 delegate says it is taking ‘real action’ on climate targets”. The Guardian. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ Volcovici, Valeria; James, William; Spring, Jake (11 November 2021). “U.S. and China unveil deal to ramp up cooperation on climate change”. Reuters. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “An investigation into what has shaped Xi Jinping’s thinking”. The Economist. 28 September 2022. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Myers, Steven Lee (5 March 2018). “Behind Public Persona, the Real Xi Jinping Is a Guarded Secret”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ McGregor, Richard (21 August 2022). “Xi Jinping’s Radical Secrecy”. The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Blachard, Ben (17 November 2017). “Glowing profile cracks door open on private life of China’s Xi”. Reuters. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Forde, Brendan (9 September 2013). “China’s ‘Mass Line’ Campaign”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Levin, Dan (20 December 2013). “China Revives Mao-Era Self-Criticism, but This Kind Bruises Few Egos”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Tiezzi, Shannon (27 December 2013). “The Mass Line Campaign in the 21st Century”. The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Lee, Chi Chun (15 February 2024). “China’s Xi appeared ‘humble’ but now rules supreme, ambassador says”. Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Ide, Bill (18 October 2017). “Xi Lays Out New Vision for Communist China”. Voice of America. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ “Xi Jinping and the Chinese dream”. The Economist. 4 May 2013. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Moore, Malcolm (17 March 2013). “Xi Jinping calls for a Chinese dream”. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Fallows, James (3 May 2013). “Today’s China Notes: Dreams, Obstacles”. The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- ^ M., J. (6 May 2013). “The role of Thomas Friedman”. The Economist. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2019.