The iconic painting depicting the surrender of the Pakistani Army chief after the 1971 war was relocated from the Indian Army Chief’s lounge, sparking controversy. The move has led to a debate over its significance and whether it was an attempt to downplay a key historical moment.

The relocation of the iconic 1971 Surrender painting from the Army Chief’s lounge has sparked a heated controversy, with political leaders and parties weighing in on the issue. The painting, which depicts the historic surrender of the Pakistani Army chief after the 1971 war, has long been seen as a symbol of India’s military victory.

The Congress-led Opposition has strongly criticized the move, accusing the Narendra Modi government of attempting to “erase history” that does not fit their political narrative. They argue that relocating such an iconic image undermines the significance of the event and the sacrifices made during the war.

Opposition leaders have expressed concerns that this move is part of a broader effort to manipulate or sanitize historical facts, altering national memory to suit the current government’s agenda. They contend that the painting serves as an important reminder of India’s triumph and the need to honor the historical context that led to the creation of Bangladesh.

In response, government representatives have defended the decision, asserting that the relocation is merely part of routine changes in office decor and does not diminish the importance of the 1971 victory. They have also emphasized the government’s commitment to preserving national history.

The controversy highlights the ongoing political battle over the interpretation and representation of history, with each side accusing the other of distorting the past for political gain. As the debate intensifies, the issue is likely to remain a point of contention in the political landscape.

The painting, which depicts the surrender of the Pakistani Army to India after the end of the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, is a powerful symbol of India’s decisive military victory over Pakistan. It represents not only the triumph in the 1971 war but also marks a significant moment in the history of the Indian subcontinent, leading to the creation of Bangladesh. The image encapsulates India’s strategic success and is seen as a reminder of the country’s military strength in the conflicts fought between the two neighboring nations. The painting holds a special place in India’s military history and national consciousness.

COURTESY: Defence Direct Education

Amid the ongoing controversy, the iconic 1971 Surrender painting was relocated to the Manekshaw Centre in Delhi Cantonment on December 16, a date commemorated as Vijay Diwas in India, marking India’s victory over Pakistan in the 1971 war. The painting, which depicts the momentous surrender of the Pakistani Army to India, is a symbol of India’s decisive military victory, which led to the creation of Bangladesh. It holds immense significance in India’s military history, as it represents a turning point in India’s defense and its victory in the three wars fought between India and Pakistan.

The relocation of this historic painting has sparked controversy, particularly among opposition leaders. The Congress-led opposition has accused the Narendra Modi government of attempting to “erase history” or downplay moments that do not align with their political narrative. They argue that removing such a symbol from a prominent place in the Army Chief’s lounge could diminish its historical importance and shift national attention away from this pivotal moment in Indian history.

On the other hand, government representatives have defended the move, claiming that the relocation was part of regular changes in office decor, with no intention to erase the painting’s significance. The decision to place it at the Manekshaw Centre, a site dedicated to military history, may be seen as a way to preserve its legacy while maintaining a space for reflection on India’s military achievements.

This controversy highlights the ongoing political struggle over the interpretation and presentation of history in India, with both sides asserting different views on how the past should be remembered and commemorated.

COURTESY: Arzoo Kazmi

What does the 1971 Surrender portrait depict?

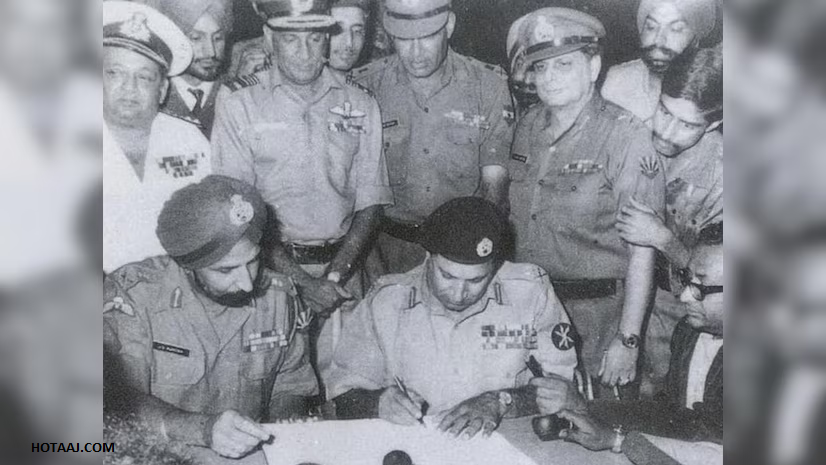

The 1971 Surrender portrait captures the historic moment when Pakistani General AAK Niazi signed the Instrument of Surrender on December 16, 1971, effectively marking the end of the Bangladesh Liberation War. The iconic image shows Lt. General Niazi signing the surrender document in front of Indian Army’s Lt. General Jagjit Singh Aurora, symbolizing India’s decisive victory. Following this moment, over 93,000 Pakistani soldiers laid down their arms, making it one of the largest surrenders in military history. This moment not only led to the creation of Bangladesh but also solidified India’s position as a regional military power, marking a significant chapter in India’s military history.

The 1971 war, lasting just 13 days from December 3 to December 16, was triggered by Pakistan’s military crackdown in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), aiming to suppress a pro-independence movement after the 1970 elections. The crackdown led to widespread violence, causing millions of refugees to flee into India, further escalating tensions. In response, the Indira Gandhi-led Indian government intervened both directly and indirectly, providing support to the Bangladesh liberation forces. India trained and armed these forces, creating significant internal resistance against the Pakistani military. India’s military intervention played a crucial role in the eventual victory and the creation of Bangladesh, marking a decisive moment in South Asian history.

The surrender took place at the Racecourse Ground (now Suhrawardy Udyan) in Dhaka, where Pakistani General AAK Niazi officially signed the Instrument of Surrender on December 16, 1971. The victory was monumental for India, as it not only led to the liberation of East Pakistan, resulting in the creation of Bangladesh, but also brought significant military gains in West Pakistan. Indian forces captured key territories, including areas in Lahore and Sindh, further solidifying India’s strategic dominance in the region. The 1971 victory was a defining moment in India’s military history, marking a decisive defeat for Pakistan and a reshaping of South Asia’s geopolitical landscape.

However, at the end of the 1971 war, India chose to return most of the captured territories in West Pakistan during the Simla Agreement of 1972. This was done as a gesture of goodwill, with the aim of fostering lasting peace between the two nations. The agreement, signed by Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Pakistani President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, emphasized the importance of bilateral discussions and peaceful resolutions to outstanding issues. While the return of territories demonstrated India’s commitment to peace, it also set the stage for continued diplomatic engagement between India and Pakistan in the years to come.

COURTESY: Maj Gen Yash Mor

From military might to mythical valour

The 1971 Surrender portrait, which had long adorned the Army Chief’s lounge, was recently replaced by a new artwork titled ‘Karam Kshetra’ (Field of Deeds). This new piece symbolizes the valor, sacrifices, and the spirit of the Indian Army, shifting the focus towards broader themes of duty and service. While the replacement of the iconic surrender portrait has sparked controversy, with some accusing the government of attempting to downplay a key historical moment, the new artwork reflects a contemporary view of India’s military ethos. The change has ignited debates about the representation of history and the way significant events are commemorated in the present day.

The new portrait, ‘Karam Kshetra’ (Field of Deeds), features a blend of modern military imagery and mythological symbolism. The artwork prominently depicts Pangong Lake along the India-China border, reflecting the contemporary challenges faced by India’s military. It also incorporates modern military assets, including boats, all-terrain vehicles, tanks, and Apache helicopters, emphasizing the nation’s military strength and preparedness.

In addition to the military imagery, the artwork features mythological figures like Chanakya and Lord Krishna, who are shown guiding Arjuna’s chariot in the Mahabharata. This symbolism connects India’s historical and strategic wisdom with its modern-day military operations, blending ancient values with contemporary power. The portrait aims to inspire and evoke a sense of duty, honor, and national pride, representing both the legacy of India’s military heritage and its present-day capabilities.

COURTESY: NEWS9 Live

Why was the portrait relocated?

According to a report in India Today, the new portrait reflects a strategic shift in the Indian Army’s evolving focus, particularly on countering China’s growing influence in the region. The artwork, with its depiction of modern military assets and the India-China border, aligns with India’s current security priorities and challenges.

Meanwhile, the iconic 1971 Surrender painting, which had previously adorned the Army Chief’s lounge, was relocated to the Manekshaw Centre in Delhi Cantonment on December 16, coinciding with Vijay Diwas. The Army clarified that the relocation was done to make the painting accessible to a larger audience, ensuring its historical significance is preserved and shared in a space dedicated to India’s military heritage. While the relocation has sparked controversy, the Army’s statement emphasized that the decision was made with the intention of broadening the painting’s reach to those interested in the nation’s military history.

“This painting is a testament to one of the greatest military victories of the Indian Armed Forces and the commitment of India for justice and humanity for all. Its placement at the Manekshaw Centre in New Delhi will benefit a large audience due to the substantial footfall of diverse audiences and dignitaries from India and abroad at this venue,” the Army said in a statement on X (formerly Twitter). The statement further emphasized the historical importance of the 1971 Surrender painting, underscoring its role in showcasing India’s military triumph and the humanitarian values that guided the nation’s actions during the Bangladesh Liberation War. By relocating the artwork to the Manekshaw Centre, the Army aims to ensure that this significant chapter in India’s history is more accessible to a broader audience, allowing visitors to engage with and reflect on the nation’s military legacy.

However, the move to relocate the iconic 1971 Surrender painting was criticized by some military veterans. Lt Gen (retd) HS Panag expressed his disapproval in a post on the social media platform X, stating, “The photo/painting symbolising India’s first major military victory in a 1,000 years and also first as a united nation, in 1971, has been removed by a hierarchy which believes that mythology, religion, and distant fragmented feudal past will inspire future victories.” Panag’s statement highlighted concerns that the removal of such a significant historical symbol could be seen as downplaying India’s modern military achievements in favor of drawing inspiration from ancient mythology and religious symbolism. His comments reflect the ongoing debate surrounding the portrayal of India’s military history and the shifting emphasis in commemorating victories and valor.

COURTESY: InShort

What is the Opposition’s take on this?

The Congress party strongly criticized the Modi government over the relocation of the iconic 1971 Surrender painting. Party MP Priyanka Gandhi Vadra accused the government of attempting to rewrite history and downplay the achievements of the Indira Gandhi-led regime during the 1971 war. In her statement, she emphasized that the victory in the Bangladesh Liberation War was a moment of immense national pride and a defining achievement of India’s military history, under the leadership of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The Congress’ criticism highlights concerns that the government’s actions are an attempt to diminish the legacy of the previous administration, particularly the significant role played by the Congress in India’s military and political victories.

“The picture showing the Pakistan Army surrendering to India has been removed from the Army Headquarters. That picture should be put back,” Priyanka Gandhi Vadra said in Parliament on Monday. Her remarks further fueled the controversy over the relocation of the iconic 1971 Surrender painting, which has been a symbol of India’s military victory. Priyanka Gandhi’s statement in Parliament called for the restoration of the painting at its original location, urging the government to honor India’s historical achievements and ensure that they are not erased or overshadowed by contemporary narratives.

Congress MP Manickam Tagore also moved an adjournment motion in the Lok Sabha to discuss the issue, describing the decision as “troubling” and a “direct affront to the historical memory” of the 1971 war. Tagore criticized the Modi government’s move to relocate the iconic 1971 Surrender painting, emphasizing that it was an attempt to erase a pivotal moment in India’s history. He argued that the painting, which symbolizes India’s decisive victory over Pakistan, should remain at the Army Headquarters to preserve the nation’s military legacy and honor the sacrifices made during the Bangladesh Liberation War.

References

- ^ Singh Rana, Uday (27 December 2017). “20% Sailor Shortage in Navy, 15% Officer Posts Vacant In Army, Nirmala Sitharaman Tells Parliament”. News18. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ The Military Balance 2017. Routledge. 2017. ISBN 978-1-85743-900-7.

- ^ “About – The President of India”. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Bhargava, R. P. The Chamber of Prince. p. 206.

Liability with regard to Defence

This point was examined at length and it was put forward that with due regard to the obligations undertaken by the Crown to protect the States against internal commotion and external aggression, the States could not be asked to contribute the cost of the armed forces of the Crown of India. In the case of several States the price of protection was settled by the Crown and paid by the States. - ^ Jump up to:a b Sikhs Across Borders. p. 37.

In 1914, the Indian Army consisted of 39 cavalry regiments, 118 battalions of Indian infantry, and 20 battalions of Gurkha Rifles. The army contained 159,134 Indian soldiers, and 2,333 British officers (plus reserves). Together with the 70,000 troops of the British garrison of India these forces made up the “Army in India.” This army had three principal functions: first, the maintenance of internal security; second, the defence of the Indian Empire’s frontiers; and third (if necessary) the provision of a force for imperial purposes outside India.

- ^ Singh, Sarbans (1993). Battle Honours of the Indian Army 1757–1971. New Delhi: Vision Books. ISBN 978-8170941156.

- ^ “Indian Army Doctrine”. Headquarters Army Training Command. October 2004. Archived from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ “Indian Army now world’s largest ground force as China halves strength on modernisation push”. ThePrint. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “20% Sailor Shortage in Navy, 15% Officer Posts Vacant In Army, Nirmala Sitharaman Tells Parliament”. News18. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Armed forces facing shortage of nearly 60,000 personnel: Government”. The Economic Times. 27 December 2017. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ International Institute for Strategic Studies (3 February 2014). The Military Balance 2014. London: Routledge. pp. 241–246. ISBN 978-1-85743-722-5.

- ^ The Military Balance 2017. Routledge, Chapman & Hall, Incorporated. 14 February 2017. ISBN 978-1-85743-900-7.

- ^ The Military Balance 2010. Oxfordshire: Routledge. 2010. pp. 351, 359–364. ISBN 978-1-85743-557-3.

- ^ “Indian Army Modernisation Needs a Major Push”. India Strategic. February 2010. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ “India’s Military Modernisation Up To 2027 Gets Approval”. Defence Now. 2 April 2012. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Oxford History of the British Army

- ^ “About The Ministry”. Ministry of Defence, Government of India. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Editorial Team (20 July 2015). “10 Facts Which Prove Indian Army Living Up To Its Motto – “Service Before Self””. SSB Interview Tips & Coaching – SSBCrack. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016.

- ^ “Indian army official Facebook page wiki-facts, official website, motto”. GuidingHawk. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ richreynolds74 (6 February 2015). “The British Indian Army During the First World War”. 20th Century Battles. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses“Direction of Higher Defence: II”. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Harold E. Raugh, The Victorians at war, 1815–1914: an encyclopaedia of British military history (2004) pp 173–79

- ^ Lydgate, John (June 1965). Quezon, Kitchener and the Problem of Indian Army Administration, 1899–1909 (PDF). SOAS Research Online (PhD thesis). University of London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Urlanis, Boris (1971). Wars and Population. Translated by Lempert, Leo. Moscow: Progress Publishers. p. 85. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Khanduri, Chandra B. (2006). Thimayya: an amazing life. New Delhi: Knowledge World. p. 394. ISBN 978-81-87966-36-4. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ^ “Nationalisation of Officer Ranks of the Indian Army” (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India – Archive. 7 February 1947. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Kaushik Roy, “Expansion And Deployment of the Indian Army during World War II: 1939–45,”Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Autumn 2010, Vol. 88 Issue 355, pp 248–268

- ^ Sumner, p.25

- ^ “Commonwealth War Graves Commission Report on India 2007–2008” (PDF). Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ Martin Bamber and Aad Neeven (26 August 1942). “The Free Indian Legion – Infantry Regiment 950 (Ind)”. Freeindianlegion.info. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Peter Stanley, “Great in adversity”: Indian prisoners of war in New Guinea,” Journal of the Australian War Memorial (October 2002) No. 37 online Archived 8 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ For the Punjab Boundary Force, see Daniel P. Marston, “The Indian Army, Partition, and the Punjab Boundary Force, 1945–47”, War in History November 2009, vol. 16 no. 4 469–505

- ^ “Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)”. The Gazette of India. 24 September 1949. p. 1375.

- ^ “Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)”. The Gazette of India. 29 October 1949. p. 1520.

- ^ “Press Note” (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India – Archive. 6 April 1948. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ “Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)”. The Gazette of India. 11 February 1950. p. 227.

- ^ Cooper, Tom (29 October 2003). “Indo-Pakistani War, 1947–1949”. ACIG Journal. Archived from the original on 13 June 2006. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Kashmir in the United Nations”. Kashmiri Overseas Association of Canada. 28 January 1998. Archived from the original on 28 January 1998. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ “47 (1948). Resolution of 21 April 1948 [S/726]”. United Nations. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ “Indian medical unit during Korean War”. 14 March 2022. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Harrison, M. (2023). “Casualty Evacuation in Korea, 1950-53: The British Experience”. Ui Sahak. 32 (2): 503–552. PMC 10556416. PMID 37718561.

- ^ Bruce Bueno de Mesquita & David Lalman. War and Reason: Domestic and International Imperatives. Yale University Press (1994), p. 201 Archived 9 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-0-300-05922-9

- ^ Alastair I. Johnston & Robert S. Ross. New Directions in the Study of China’s Foreign Policy. Stanford University Press (2006), p. 99 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-0-8047-5363-0

- ^ Claude Arpi. India and her neighbourhood: a French observer’s views. Har-Anand Publications (2005), p. 186 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-81-241-1097-3.

- ^ CenturyChina, www.centurychina.com/plaboard/uploads/1962war.htm

- ^ Dennis Kux’s India and the United States: estranged democracies, 1941–1991, ISBN 1-4289-8189-6, DIANE Publishing, Pg 238

- ^ Dijkink, Gertjan. National identity and geopolitical visions: maps of pride and pain. Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0-415-13934-1.

- ^ Praagh, David. The greater game: India’s race with destiny and China. McGill-Queen’s Press – MQUP, 2003. ISBN 0-7735-2639-0.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c R.D. Pradhan & Yashwantrao Balwantrao Chavan (2007). 1965 War, the Inside Story: Defence Minister Y.B. Chavan’s Diary of India-Pakistan War. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. p. 47. ISBN 978-81-269-0762-5. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

- ^ Sumit Ganguly. “Pakistan”. In India: A Country Study Archived 1 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine (James Heitzman and Robert L. Worden, editors). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (September 1995).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ganguly, Sumit (2009). “Indo-Pakistan Wars”. Microsoft Encarta. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ Thomas M. Leonard (2006). Encyclopedia of the developing world, Volume 2. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-97663-3.

- ^ Spencer Tucker. Tanks: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO (2004), p. 172 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-1-57607-995-9.

- ^ Sumit Ganguly. Conflict unending: India-Pakistan tensions since 1947. Columbia University Press (2002), p. 45 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0-231-12369-3.

- ^ Mishra, Keshav (2004). Rapprochement Across the Himalayas: Emerging India-China Relations Post Cold War Period (1947–2003). Gyan Publishing House. p. 40. ISBN 9788178352947. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ Hoontrakul, Pongsak (2014). The Global Rise of Asian Transformation: Trends and Developments in Economic Growth Dynamics (illustrated ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-137-41235-5. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016.

- ^ “50 years after Sino-Indian war”. Millennium Post. 16 May 1975. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ “Kirantis’ khukris flash at Chola in 1967”. Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Lawoti, Mahendra; Pahari, Anup Kumar (2009). “Part V: Military and state dimension”. The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-first Century. London: Routledge. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-135-26168-9.

The second turning point came in the wake of the 1971 Bangladesh war of independence which India supported with armed troops. With large contingents of Indian Army troops amassed in the West Bengal border with what was then East Pakistan, the Government of Indira Gandhi used the opening provided by President’s Rule to divert sections of the army to assist the police in decisive counter-insurgency drives across Naxal–impacted areas. “Operation Steeplechase,” a police and army joint anti–Naxalite undertaking, was launched in July–August 1971. By the end of “Operation Steeplechase” over 20,000 suspected Naxalites were imprisoned and including senior leaders and cadre, and hundreds had been killed in police encounters. It was a massive counter-insurgency undertaking by any standards.

- ^ Pandita, Rahul (2011). Hello, Bastar : The Untold Story of India’s Maoist Movement. Chennai: Westland (Tranquebar Press). pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-93-80658-34-6. OCLC 754482226.

Meanwhile, the Congress government led by Indira Gandhi decided to send in the army and tackle the problem militarily. A combined operation called Operation Steeplechase was launched jointly by the military, paramilitary and state police forces in West Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

[permanent dead link]

In Kolkata, Lt General J.F.R. Jacob of the Indian Army’s Eastern Command received two very important visitors in his office in October 1969. One was the army chief General Sam Manekshaw and the other was the home secretary Govind Narain. Jacob was told of the Centre’s plan to send in the army to break the Naxal. More than 40 years later, Jacob would recall how he had asked for more troops, some of which he got along with a brigade of para commandos. When he asked his boss to give him something in writing, Manekshaw declined, saying, ‘Nothing in writing.’ while secretary Narain added that there should be no publicity and no records. - ^ Owen Bennett Jones. Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press (2003), p. 177 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0-300-10147-8.

- ^ Eric H. Arnett. Military capacity and the risk of war: China, India, Pakistan, and Iran. Oxford University Press (1997), p. 134 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0-19-829281-4.

- ^ S. Paul Kapur. Dangerous deterrent: nuclear weapons proliferation and conflict in South Asia. Stanford University Press (2007), p. 17 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0-8047-5550-4.

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Developing World, p. 806 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ North, Andrew (12 April 2014). “Siachen dispute: India and Pakistan’s glacial fight”. BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Edward W. Desmond. “The Himalayas War at the Top Of the World” Archived 14 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Time (31 July 1989).

- ^ Vivek Chadha. Low Intensity Conflicts in India: An Analysis. SAGE (2005), p. 105 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0-7619-3325-0.

- ^ Pradeep Barua. The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press (2005), p. 256 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-0-8032-1344-9.

- ^ Tim McGirk with Aravind Adiga. “War at the Top of the World”. Time (4 May 2005).

- ^ Kamal Thakur (1 November 2014). “16 Things You Should Know About India’s Soldiers Defending Siachen”. Topyaps. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ Sanjay Dutt. War and Peace in Kargil Sector. APH Publishing (2000), p. 389-90 Archived 21 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-81-7648-151-9.

- ^ Nick Easen. Siachen: The world’s highest cold war Archived 23 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. CNN (17 September 2003).

- ^ Arun Bhattacharjee. “On Kashmir, hot air and trial balloons” Archived 28 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Asia Times (23 September 2004).

- ^ “Indian Army organizes a Symposium titled “North Technical-2014″ – Scoop News Jammu Kashmir”. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ “e-Symposium – Northern Command”. Official Website of Indian Army. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ “e-Symposium – Northern Command: North Tech Symposium 2016”. Official Website of Indian Army. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ Bhaumik, Subir (10 December 2009). Troubled Periphery: The Crisis of India’s North East By Subir Bhaumik. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9788132104797. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017.

- ^ Indian general praises Pakistani valour at Kargil 5 May 2003 Daily Times, Pakistan Archived 16 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kashmir in the Shadow of War By Robert Wirsing Published by M.E. Sharpe, 2003 ISBN 0-7656-1090-6 pp36

- ^ Managing Armed Conflicts in the 21st Century By Adekeye Adebajo, Chandra Lekha Sriram Published by Routledge pp192,193

- ^ The State at War in South Asia By Pradeep Barua Published by U of Nebraska Press Page 261

- ^ “Tariq Ali · Bitter Chill of Winter: Kashmir · LRB 19 April 2001”. London Review of Books. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Colonel Ravi Nanda (1999). Kargil : A Wake Up Call. Vedams Books. ISBN 978-81-7095-074-5. Online summary of the Book Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Alastair Lawson. “Pakistan and the Kashmir militants” Archived 28 February 2003 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News (5 July 1999).

- ^ A.K. Chakraborty. “Kargil War brings into sharp focus India’s commitment to peace” Archived 18 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Government of India Press Information Bureau (July 2000).

- ^ Michael Edward Brown. Offense, defence, and war. MIT Press (2004), p. 393 Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sameer Yasir (21 September 2016), “Uri attack carried out by Jaish-e-Mohammad militants, confirms Indian Army”, Firstpost

- ^ “India’s surgical strikes across LoC: Full statement by DGMO Lt Gen Ranbir Singh”. Hindustan Times. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ “Uri avenged: 35–40 terrorists, 9 Pakistani soldiers killed in Indian surgical strikes”. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016.

- ^ “Surgical strikes in PoK: How Indian para commandos killed 50 terrorists, hit 7 camps”. India Today. 29 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ “Video footage provides proof of surgical strikes across LoC | News- Times of India Videos ►”. The Times of India. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ “Surgical strikes video out, shows terror casualties, damage to bunkers”. The Indian Express. 28 June 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ Excelsior, Daily (4 June 2018). “BSF carries out 9 major strikes on Pak; 10 posts, bunkers decimated”.

- ^ “Indian Army’s 21-year-old Rifleman killed in ceasefire violation”. The Economic Times. 16 June 2018.

- ^ Safi, Michael; Farooq, Azhar (15 February 2019). “Dozens of Indian paramilitaries killed in Kashmir car bombing”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

The Pakistan-based militant group Jaish-e-Mohammed claimed responsibility for the bombing. It said it was carried out by Adil Ahmad Dar, a locally recruited fighter from south Kashmir’s Pulwama district. The group released a video showing Dar delivering his will and a photograph of him surrounded by guns and grenades

- ^ Safi, Michael; Farooq, Azhar (15 February 2019). “Dozens of Indian paramilitaries killed in Kashmir car bombing”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

We will give a befitting reply, our neighbour will not be allowed to de-stabilise us”, Modi said

- ^ Abi-Habib, Maria; Yasir, Sameer; Kumar, Hari (15 February 2019). “India Blames Pakistan for Attack in Kashmir, Promising a Response”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

Pakistan has denied involvement in the attack, in which at least 40 Indian soldiers were killed Thursday when a driver slammed an explosives-packed vehicle into a paramilitary convoy.

- ^ Joanna Slater (26 February 2019), “India strikes Pakistan in severe escalation of tensions between nuclear rivals”, The Washington Post

- ^ Safi, Michael; Zahra-Malik, Mehreen (27 February 2019). “‘Get ready for our surprise’: Pakistan warns India it will respond to airstrikes”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

Pakistan, said the war planes made it up to five miles [eight kilometres] inside its territory

- ^ Gul, Ayaz (22 March 2019). “Pakistani PM Receives National Day Greetings from Indian Counterpart”. VOA. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ “Pakistan welcomes India’s peace offer | Pakistan Today”. Pakistan Today.

- ^ [1] Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Past peacekeeping operations”. United Nations Peacekeeping. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ “United Nations peacekeeping – Fatalities By Year up to 30 June 2014” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 July 2017.

- ^ John Cherian (26 May – 8 June 2001). “An exercise in anticipation”. Frontline. Vol. 18, no. 11. Archived from the original on 7 December 2004. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ “India, Mongolia engage in joint military exercises”. Business Standard. 11 June 2013. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ Exercise Nomadic Elephant, Indo Mongolian Joint Military Exercise Archived 18 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Facebook (24 June 2013). Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ “Indian Army tests network-centric warfare capability in Ashwamedha war games”. India-defence.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ “‘Ashwamedha’ reinforces importance of foot soldiers”. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ “Yudh Abhyas enhances U.S., Indian Army partnership”. Hawaii Army Weekly. 22 May 2013. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ “Steele_August2013.pdf – Association of the United States Army” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013.

- ^ Sgt. Michael J. MacLeod (11 May 2013). “Yudh Abhyas 2013 Begins”. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ “File:Sgt. Balkrishna Dave explains weapons-range safety procedures to Indian Army soldiers with the 99th Mountain Brigade before they fire American machine guns.jpg”. 3 May 2013. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ “Indo-French joint Army exercise Shakti 2013 begins today”. Zeenews.india.com. 9 September 2013. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ “Indo-French Joint Army Exercise “Shakti 2016″”. Facebook. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ “Indian Army gears up for war game in Rajasthan desert”. FacenFacts. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ “Western Army Command conducts summer training exercises”. Business Standard India. 11 May 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ “Indian Army’s firing exercise ‘Shatrujeet’ enters its last phase – Times of India”. The Times of India. 17 April 2016. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ “Indian Army Conducts Battle Exercise ‘Shatrujeet’ In Rajasthan”. NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ “Indian Army Test Its Operation Abilities”. News Ghana. 17 April 2016. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ “Army and navy plan to set up a marine brigade”. Indiatoday.intoday.in. 9 June 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ “Peninsular command by next year end, theatre commands by 2022: Gen. Rawat”. The Hindu. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ “Lt. General Upendra Dwivedi appointed new Army Chief”. The Indian Express. 11 June 2024. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m “Know Your Army: Structure”. Official Indian Army Web Portal. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ “Lt Gen Anindya Sengupta takes over as GOC-In-C, Central Command”. The Times of India. 2 July 2024. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ “Lieutenant General Ram Chander Tiwari assumes charge of Eastern Command”. The Economic Times. 2 January 2024. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ “Eye on China, India to raise second division for mountain corps”. The Indian Express. 17 March 2017. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ “The mountain is now a molehill”. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Service, Statesman News (20 February 2024). “Lt General Suchindra Kumar takes charge of Army’s Northern Command”. The Statesman. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Philip, Snehesh Alex (12 April 2021). “These are the key changes Army has made in Ladakh to counter China in summer”. ThePrint. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ “Lt Gen Dhiraj Seth assumes command of Southern Army”. The Indian Express. 1 July 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Service, Statesman News (1 July 2024). “Lt Gen Manjinder Singh assumes charge of South-Western Command”. The Statesman. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ “Lt Gen Manoj Kumar Katiyar takes over as Western Command GOC-in-C”. Hindustan Times. 2 July 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ “Lt General Devendra Sharma Takes Over As New Army Training Command Chief”. English Jagran. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ “DG Armoured Corps”. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ “Lieutenant General Adosh Kumar assumed appointment of the Director General of Artillery on 01 May 2023”. 1 May 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ “Goan Native Sumer Ivan D’Cunha Promoted To Lieutenant General”. Free Press Journal. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ “Lt Gen Vinod Nambiar assumed the appointment of Director General & Colonel Commandant of Army Aviation – ADGPI Twitter”. X (formerly twitter). Retrieved 2 August 2024.

- ^ “Lt Gen Arvind Walia appointed next Engineer-in-Chief of Indian Army”. 26 December 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ “With Lt General MU Nair heading to NDCS, Major General KV Kumar likely as next Signals Chief”. The Economic Times. 3 July 2023. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ “Lt Gen Samantara flags off bike expedition at Delhi”. Brighter Kashmir. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ “Government will ensure best of weapons and protective armours to our soldiers: Raksha Rajya Mantri Shri Shripad Yesso Naik”. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ Deshpande, Smruti (5 July 2024). “India set to carry out trials for US-made Stryker combat vehicles in Ladakh & deserts”. ThePrint. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ “Indian Army and Anti-Tank Guided Missile”. Strategic Front Forum – Indian Defence and Strategic Forum. 3 December 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ “Infantry Regiments”. Bharat Rakshak. 2008. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ “Indian artillery inflicted maximum damage to Pak during Kargil”. Zee News. 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ RAGHUVSNSHI, VIVEK (21 March 2014). “Upgraded Indian Howitzers Cleared for Summer Trials”. defensenews.com. Gannett Government Media. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ Swami, Praveen (29 March 2012). “Inside India’s defence acquisition mess”. The Hindu. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ “In ‘Dhanush’, Indian Army’s Prayers Answered”. NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ “Defence ministry agrees to army’s long pending demand of artillery guns”. dna. Archived from the original on 24 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ “Indigenous Artillery Gun ‘Dhanush’ to be Ready This Year”. The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 22 November 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ “Indian Army to increase indigenous rocket regiments by 2022”. Firstpost. 7 December 2016. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Brett-James, Antony Report my Signals London Hennel Locke 1948 – personal account of a British officer attached to Indian Army in Egypt and Burma

- ^ “Corps Of Signals – Inaugural: Ceremony Centenary Year”. Ministry of Defence. 15 February 2010. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ Rishabh Mishra (24 June 2015). “21 Different Branches Of Indian Army That Make It Such An Efficient Defence Force”. TopYaps. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ “Lieutenant General Sadhna Saxena Nair assumes charge as Director General Medical Services (Army)”. The Hindu. 1 August 2024. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- ^ Som, Vishnu (16 May 2020). “Anand Mahindra May Recruit Those Who Served In Army’s New 3-Year ‘Tour Of Duty’ Scheme”. NDTV. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ “What is Tour of Duty in Indian Army – Times of India”. The Times of India. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Explained: The Agnipath scheme for recruiting soldiers – what is it, how will it work?”. The Indian Express. 15 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Singh, Sushant (16 June 2022). “‘Agnipath’: What is India’s new military recruitment system?”. www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ De, Abhishek (18 June 2022). “Why Is There So Much Anger Against Agnipath Scheme, Especially In North India?”. news.abplive.com. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ “What is Agnipath scheme: Why Agniveer aspirants in Bihar protesting against it”. Daily News & Analysis. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ “Put Agnipath on hold, take it up in Parliament: Opposition”. The Times of India. TNN. 17 June 2022. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ “How Indian Army’s Military Intelligence Directorate works : Special Report – India Today”. Indiatoday.intoday.in. 28 January 2012. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ “State govt allots land for NTRO in Borda village”. IBNLive. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ “What is STEAG, Army’s new elite tech unit”. The Times of India. 18 March 2024. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Richard Rinaldi; Ravi Rikhye (2010). Indian Army Order of Battle. General Data LLC. ISBN 978-0-9820541-7-8. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016.

- ^ “Know about Ghatak commandos, the invincible Special Forces of India”. 10 February 2014. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ “National War Memorial (Rashtriya Samar Smarak)”. nationalwarmemorial.gov.in. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ “The mountain is now a molehill”. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ “More soldiers but weaker Army”. dailypioneer.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ (Iiss), The International Institute of Strategic Studies (14 February 2020). The Military Balance 2020. Routledge, Chapman & Hall, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-367-46639-8.

- ^ “General V K Singh takes over as new Indian Army chief”. The Times of India. 31 March 2010. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ Page, Jeremy. “Comic starts adventure to find war heroes” Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. The Times (9 February 2008).

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Indian Army Rank Badges”. indianarmy.nic.in. Indian Army. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ “14 Different Uniforms of Indian Army”. Defence Directed Education (DDE). 1 June 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ “Army to adopt new combat fatigues next year”. 15 January 2022.

- ^ “Indian Army Day 2022: Indian Army unveils new combat uniform with a digital disruptive pattern”. Firstpost.com. 15 January 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ “Lighter fabric to unique pattern, here’s how NIFT team created Indian Army’s new combat uniform”. The Indian Express. 18 January 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ “New Army Combat Uniforms for Troops Only Through Fixed Channels, Fabric Won’t Be Sold in Open Market”. News18. 4 February 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ “Dr Seema Rao: India’s First Female Combat Trainer, Fighting Stereotypes”. Forbes India.

- ^ Indian Army must stop its discrimination against military nurses Archived 14 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Hindustan Times, 13 December 2017.

- ^ “Entry Schemes Women : Officers Selection – Join Indian Army”. joinindianarmy.nic.in. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ “Agniveer Yojana – MyGov.in”. MyGov.in. 14 June 2022. Archived from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ “Agneepath Scheme Details, Apply Online, Age Limit, Salary, Eligibility, etc. – Agneepath Scheme”. 19 July 2024. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Singh, Rahul (14 June 2022). “Recruitment model for soldiers to create an ‘Agniveer’ rank”. Hindustan Times. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ The Indian Expresshttps://agneepathscheme.in/

- ^ “TF_Oct_2021.pdf” (PDF). Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ “Our History”. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Pandit, Rajat (24 March 2014). “Army running low on ammunition”. indiatimes.com. TNN. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ PTI. “HAL developing light choppers for high-altitude operations”. The Hindu Business Line. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ Gautam Datt (13 October 2012). “Army to get attack helicopters: Defence Ministry”. Mail Today (epaper). Archived from the original on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ “DRDO’s F-INSAS programme to be ready in two years”. Defence News. 9 July 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Pandit, Rajat. “Army to raise 2 mountain units to counter Pak, China” . The Times of India, 7 February 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ Rajat Pandit, Eye on China, is India adding muscle on East? 2 2009 July 0325hrs

- ^ “Army to set up new corps for operations along LAC”. The Indian Express. 20 February 2024. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Philip, Snehesh Alex (20 February 2024). “Army’s Central Command gets ‘combatised’ to counter China, new corps raised”. ThePrint. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ “Indian Army to set up new corps for operations along LAC”. Indian Army to set up new corps for operations along LAC. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ “Indian Army Mulls XVIII Corps Formation for Enhanced Border Security with China”. Financialexpress. 25 February 2024. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ “Indian Army plans aggressor red team, test-bed units in modernisation drive”. www.business-standard.com. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ “India to deploy Integrated Battle Groups to counter China days after border truce”. India Today. 5 November 2024. Archived from the original on 30 November 2024. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ “Defence Ministry clears 70,000 Sig Sauer assault rifles for Indian Army”. The Times of India. 12 December 2023. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Shiv Aroor (1 November 2018). “Mega Made-In-India Kalashnikov Assault Rifle Deal Around The Corner”. Livefist Defence.com. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ “Indigenisation of Indian defence sector gets a 1,100-gun boost”. News9live. 6 April 2024. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ “Exclusive: Made in India rifles to replace INSAS”. 5 July 2015. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ “Arjun, Dhruv Get Thumbs Up From Indian Army Chief”. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ “Night-vision devices for Indian Army approved”. Zee News. 2 April 2013. Archived from the original on 8 June 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ “Army to get night vision devices worth over Rs 2,800 crore for its tanks and infantry combat vehicles”. The Economic Times. 2 April 2013. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Army eyes Rs 57,000cr project to make combat vehicles to replace T-72 tanks”. The Times of India. 19 February 2024. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ “Indian Army plans Rs 57,000 crore project to replace 1,800 aging Russian T-72 tanks with advanced AI battle machine”. The Economic Times. 19 February 2024. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ “India begins receiving 8×8 TATA WhAP Wheeled Armored Amphibious Platform”. Frontier India. 3 April 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Hoyle, Craig (2023). “World Air Forces 2024”. FlightGlobal. Retrieved 27 December 2023.

- ^ “IAF’s Strengthened Arsenal: Acquisition of 97 Tejas Mk1A Jets Marks a Milestone”. Financialexpress. 30 November 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ “Indian Army may procure over 90 light utility helicopters from HAL in a landmark deal”. Zee Business. 8 November 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ “Prahaar Missile to be test-fired on Sunday”. Ibnlive.in.com. 17 July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Peri, Dinakar (8 June 2023). “DRDO successfully flight-tests New Generation Ballistic Missile ‘Agni Prime’ off Odisha”. The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ “India notches MIRV tech success in Agni-V firing, Pakistan failed three years ago”. Hindustan Times. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ “India completes phase one of ballistic missile defence programme, nod for missiles awaited”. The Print. 23 April 2019. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ “155-mm gun contract: DRDO enters the fray”. Business Standard India. Business-standard.com. 29 July 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Unnithan, Sandeep (12 August 2021). “Why L&T is offering the Indian army a homegrown artillery gun”. India Today. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Indian Army orders 100 additional K9 howitzers”. Janes.com. 20 February 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ “Indian Army Intends To Purchase 1200 Advanced Towed Gun Systems (TGS)”. theigmp.org. October 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ “India clears acquisition of mounted gun system”. Janes.com. 10 February 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ Snehesh Alex Philip (20 February 2023). “New barrel, extended range – India & US explore joint development of M777 howitzer variant”. ThePrint. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ “Indian Military News Headlines”. Bharat-Rakshak.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.