Baltic Sea Tensions Rise Amid Undersea Cable Damage and NATO Response

The Baltic Sea has become a focal point of heightened tensions as Estonia and Finland respond to suspected sabotage of critical undersea power infrastructure. Estonia’s navy deployed the patrol vessel Raju to protect the remaining operational Estlink 1 power cable, after the Estlink 2 cable was severely damaged in what EU officials have described as an attack on critical infrastructure.

Incident Overview

The damage to the Estlink 2 cable, a 170km (105-mile) link between Estonia and Finland, occurred in the Gulf of Finland. Finnish authorities have detained the oil tanker Eagle S, suspected of involvement in the incident. The EU has identified the vessel as part of “Russia’s shadow fleet,” a term used for ships allegedly linked to clandestine Russian operations.

NATO and Regional Responses

NATO has pledged to enhance its military presence in the Baltic Sea, with Secretary General Mark Rutte emphasizing vigilance and support for member nations. Estonia and Finland, both NATO members, are considering invoking Article 4 of the NATO Treaty, which allows for consultations if a member feels threatened.

Estonian Prime Minister Kristen Michal expressed a desire for NATO reinforcements, including a naval fleet, to deter further threats. Estonia’s Defense Minister Hanno Pevkur confirmed that Finland is expected to join the operation to safeguard the Estlink 1 cable.

Impact on Energy Supply

The damage to Estlink 2 has significantly disrupted Estonia’s power supply. Initial assessments by Finland’s Fingrid energy company indicate repairs may not be completed until July 2025, leaving Estonia reliant on the single remaining cable for its energy connection to Finland.

Third Incident in a Month

This marks the third significant incident in the Baltic Sea in just over a month, raising concerns about the security of critical infrastructure in the region. The EU has called for increased vigilance, citing a pattern of suspected attacks.

Russia’s Position

The Kremlin has refrained from commenting directly on the incident, describing it as a “very narrow issue” and not a matter for the Russian presidency. However, the accusations have deepened existing mistrust between Russia and NATO-aligned countries in the Baltic region.

Future Steps

As the investigation continues, NATO, Estonia, and Finland are intensifying their efforts to secure critical infrastructure. The situation underscores the growing importance of regional cooperation and military preparedness in the face of emerging hybrid threats.

Broader Implications for Regional Security

The damage to the Estlink 2 cable has heightened regional concerns about the vulnerability of critical infrastructure in the Baltic Sea, an area of strategic importance. This incident adds to growing apprehension about unconventional threats, including cyberattacks and sabotage, targeting energy and communication links that are vital to national security and economic stability.

NATO’s decision to bolster its presence in the region reflects a broader strategy to address emerging hybrid threats. The alliance’s commitment to supporting Estonia and Finland highlights the importance of collective defense and deterrence.

Potential Article 4 Invocation

The potential invocation of Article 4 of the NATO Treaty underscores the seriousness of the situation. This would initiate formal consultations among NATO members and could lead to a coordinated response. While Estonia and Finland have not yet activated the clause, the option remains on the table as they assess the situation’s impact on their national security.

EU and International Reactions

The European Union has expressed solidarity with Estonia and Finland, condemning the suspected attack on Estlink 2 as part of a broader pattern of aggression. EU officials have called for enhanced monitoring and protection of undersea infrastructure, urging member states to invest in resilient systems and collaborative security measures.

Economic Repercussions

The shutdown of Estlink 2 has not only strained Estonia’s power supply but also highlighted the economic vulnerabilities associated with disrupted energy flows. Extended repair timelines—potentially until mid-2025—pose challenges for energy markets and underscore the importance of diversifying supply routes and enhancing grid security.

Third Baltic Sea Incident: A Pattern Emerges

The Estlink 2 damage is the third such incident in the Baltic Sea in recent weeks. Earlier cases involved suspected sabotage of communication cables and other infrastructure. These incidents suggest a deliberate strategy to disrupt critical systems and test the resilience of NATO and EU member states.

Geopolitical Context

The Baltic Sea region has long been a theater of geopolitical rivalry, with increased tensions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The presence of Russia’s “shadow fleet” in the area adds complexity, as it raises questions about covert operations and accountability.

Military and Technological Measures

In response to these challenges, NATO and its allies are likely to accelerate investments in undersea monitoring technologies, cybersecurity, and rapid-response capabilities. Enhanced naval patrols, such as Estonia’s deployment of the Raju, are part of a broader strategy to deter and respond to threats.

Public and Political Sentiment

The incidents have also sparked public debate in Estonia and Finland about national security and defense readiness. Both governments face pressure to demonstrate decisive action and strengthen their defenses against unconventional threats.

Looking Ahead

As the investigation into the Estlink 2 damage continues, the incident serves as a wake-up call for the international community. Protecting critical infrastructure in an era of hybrid warfare requires coordinated efforts, technological innovation, and unwavering commitment to collective security. Estonia and Finland’s handling of this crisis will set a precedent for future responses to similar threats in the region and beyond.

Recent Baltic Sea Incidents Raise Concerns Over Undersea Infrastructure Security

Recent months have witnessed a troubling series of incidents targeting critical undersea infrastructure in the Baltic Sea. These events have heightened geopolitical tensions and underscored vulnerabilities in the region’s energy and communication networks.

Timeline of Incidents

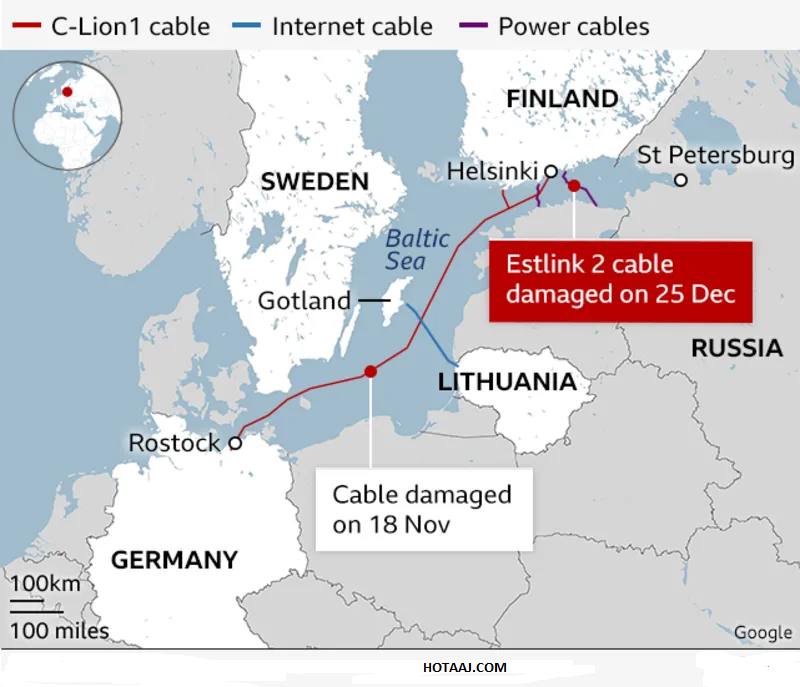

- 17 November 2024:

- The Arelion data cable between Gotland, Sweden, and Lithuania was severed.

- This was followed by damage to the C-Lion 1 cable linking Helsinki, Finland, and Rostock, Germany.

- Investigations suggest a Chinese ship, Yi Peng 3, may have dragged its anchor over the cables in a suspected act of Russian sabotage.

- October 2023:

- Another Chinese vessel damaged an undersea gas pipeline between Finland and Estonia, further disrupting energy supplies in the region.

- Ongoing Incidents:

- The Yi Peng 3 and Eagle S, both part of a suspected “shadow fleet” of oil tankers linked to Russia, are under scrutiny for their roles in these acts of sabotage.

Shadow Fleet and Western Sanctions

The “shadow fleet” comprises vessels allegedly being used by Russia to evade Western sanctions imposed after its invasion of Ukraine. These ships have been implicated in covert activities, including disruptions to infrastructure and illegal oil transportation.

Geopolitical Implications

- Hybrid Warfare: The incidents are seen as part of a broader strategy of hybrid warfare, combining conventional military threats with sabotage and economic destabilization.

- NATO and EU Response: These events have prompted calls for enhanced regional security measures, with NATO vowing to increase its presence in the Baltic Sea.

- China’s Role: The involvement of Chinese vessels has added another layer of complexity, raising questions about Beijing’s potential alignment with Moscow’s strategic goals.

Impact on Critical Infrastructure

The deliberate targeting of undersea cables and pipelines is particularly alarming due to their importance in energy and data transmission. These attacks:

- Disrupt essential services.

- Highlight the vulnerability of undersea infrastructure to sabotage.

- Undermine confidence in regional stability and security.

Call for Strengthened Monitoring and Defense

In response to these threats, regional actors, including Estonia, Finland, and NATO, are exploring measures to safeguard their infrastructure. Proposals include:

- Increased naval patrols.

- Deployment of advanced monitoring technologies.

- Greater investment in cybersecurity and resilience.

A Strategic Warning

The incidents in the Baltic Sea serve as a stark warning about the evolving nature of modern conflict, where infrastructure sabotage plays a key role in destabilizing nations. Collaborative efforts among NATO, the EU, and regional governments will be crucial in mitigating these threats and ensuring the security of critical infrastructure.

Escalating Undersea Tensions in the Baltic Sea: Broader Context and Strategic Implications

The ongoing incidents in the Baltic Sea underscore the rising risks to undersea infrastructure as geopolitical tensions intensify. The suspected sabotage of power cables, pipelines, and data links by shadow fleets has not only disrupted services but also brought the region’s security vulnerabilities into sharp focus.

Deepening Complexity in Recent Incidents

- Pattern of Targeted Disruption:

- The damage to Arelion, C-Lion 1, and Estlink 2, combined with the earlier gas pipeline rupture, represents a clear escalation in targeted strikes on critical systems.

- Analysts note the strategic targeting of assets integral to energy and digital connectivity between NATO and EU nations.

- Role of Shadow Fleets:

- The Yi Peng 3 and Eagle S are part of a broader network allegedly used by Russia to bypass sanctions while engaging in covert operations.

- Their movements near sensitive areas raise concerns about the increasing militarization of what were once civilian maritime assets.

- China’s Involvement:

- China’s suspected indirect involvement through the use of its vessels complicates international diplomacy, as Beijing continues to assert neutrality publicly while its actions suggest otherwise.

Strategic Reactions and Preparations

- NATO’s Bolstered Presence:

- NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte announced increased military vigilance in the Baltic Sea. While specific deployments remain undisclosed, sources indicate plans for:

- Enhanced maritime patrols.

- Deployment of surveillance drones.

- Intelligence sharing among NATO allies.

- Article 4 Consultations:

- Estonia and Finland are considering invoking Article 4 of the NATO Treaty, signaling a perceived threat to their sovereignty and security. This could lead to broader NATO involvement, including naval reinforcements.

- EU Solidarity Measures:

- The European Union has condemned these attacks as part of a “wider assault on critical infrastructure,” and discussions are underway to bolster regional resilience, including funding for undersea monitoring systems.

Economic and Technological Impact

- Energy Shortages:

- Estonia’s reliance on the Estlink 2 cable for power has left the nation facing potential outages and increased dependency on alternative sources, raising energy costs.

- Prolonged repairs to damaged cables, estimated to last until mid-2025, will strain resources and heighten vulnerability.

- Data Connectivity Risks:

- Severed data cables disrupt financial transactions, internet connectivity, and communication networks, impacting not just regional but global systems dependent on uninterrupted data flow.

Long-Term Strategic Threats

- Infrastructure as a Battlefield:

- The recent incidents reflect a growing trend where infrastructure is a key target in geopolitical disputes. This form of hybrid warfare allows adversaries to exert influence without direct military confrontation.

- Escalation Risks:

- If investigations substantiate claims of Russian involvement, tensions between NATO and Russia could escalate, with the Baltic region becoming a potential flashpoint.

- Similarly, China’s indirect role could lead to wider geopolitical ramifications, involving the Indo-Pacific and transatlantic alliances.

Policy Recommendations

- Regional Cooperation:

- Baltic nations must collaborate closely with NATO and the EU to develop a cohesive security strategy.

- Technological Investment:

- Funding advanced sonar systems, autonomous underwater vehicles, and AI-powered monitoring solutions will be critical in detecting and deterring future threats.

- Enhanced Sanction Mechanisms:

- Targeting shadow fleets and their logistical networks can disrupt operations and hold state actors accountable for covert activities.

Conclusion

The series of attacks on undersea cables and pipelines in the Baltic Sea highlights a dangerous shift in modern conflict dynamics. Beyond immediate security concerns, these incidents pose long-term challenges to regional stability, international cooperation, and critical infrastructure protection. A robust, unified response by NATO, the EU, and affected nations is essential to counter these emerging threats and secure the region’s future.

Escalating Tensions in the Baltic: EU Targets “Russia’s Shadow Fleet” Amid Infrastructure Sabotage

The European Union is ramping up efforts to address security threats posed by what it describes as “Russia’s shadow fleet,” suspected of undermining critical undersea infrastructure. Recent events in the Baltic Sea, including sabotage of power and data cables, have heightened geopolitical tensions and exposed vulnerabilities in the region.

Sanctions and Investigations Underway

The EU announced plans for targeted sanctions against Russia’s clandestine fleet, citing both security risks and environmental hazards. This initiative follows multiple incidents of cable and pipeline damage attributed to these covert operations.

Recent Developments

- Chinese Tanker in Kattegat Strait

- A Chinese tanker, anchored in the Kattegat strait between Sweden and Denmark for weeks, became the focus of a multi-nation boarding operation by Sweden, Denmark, Germany, and Finland.

- Despite the intervention, the tanker departed last week, raising further questions about enforcement capabilities and intentions.

- Eagle S Boarding in Finland

- Finnish authorities intercepted and boarded the Cook Islands-registered Eagle S on Thursday. The vessel was escorted off Porkkala, directly across from Tallinn in the Gulf of Finland.

- Key Observation: Finnish patrol vessels noted the Eagle S was missing its anchor, a detail that could connect the ship to cable damage incidents.

Assurances and Challenges

- Estonian Prime Minister’s Statement

- The Estonian leader reassured citizens that the country’s energy supply would remain secure, citing backup power arrangements with energy providers Elering and Eesti Energia.

- Security Limitations

- While efforts are underway to safeguard undersea infrastructure, officials admitted that protecting every square meter of the seabed is unfeasible, leaving certain vulnerabilities exposed.

Context of the Shadow Fleet

The so-called “shadow fleet” comprises vessels allegedly deployed by Russia to bypass Western sanctions while engaging in disruptive activities. These operations have raised concerns about the broader implications for maritime security and environmental protection.

Broader Implications

- Energy Security

- Damaged cables and pipelines in the Baltic Sea have intensified discussions on energy independence and the need for robust infrastructure protection.

- Geopolitical Dynamics

- The incidents highlight growing collaboration among EU and NATO members to counter hybrid threats while underscoring challenges posed by Chinese involvement in shadow operations.

Looking Ahead

With EU sanctions and NATO’s bolstered presence in the Baltic Sea, the region is preparing for prolonged efforts to counteract these covert threats. Enhanced monitoring, international cooperation, and strategic investments in undersea security will play a critical role in addressing this emerging crisis.

COURTESY: Al Jazeera English

References

- ^ “The NATO Russian Founding Act | Arms Control Association”. www.armscontrol.org. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Benson, Brett V. (2012). Constructing International Security: Alliances, Deterrence, and Moral Hazard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1107027244.

- ^ “Russia says deployment of EU mission in Armenia to ‘exacerbate existing contradictions'”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b RAND, Russia’s Hostile Measures: Combating Russian Gray Zone Aggression Against NATO in the Contact, Blunt, and Surge Layers of Competition (2020) online

- ^ “Twenty Years of Russian “Peacekeeping” in Moldova”. Jamestown. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ “President of Russia”. 2 September 2008. Archived from the original on 2 September 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew; Erlanger, Steven (27 February 2014). “Gunmen Seize Government Buildings in Crimea”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Ellyatt, Holly (24 February 2022). “Russian forces invade Ukraine”. CNBC. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ “Russia joins war in Syria: Five key points”. BBC News. 1 October 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ “Russia blocks trains carrying Kazakh coal to Ukraine | Article”. 5 November 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Russia suspends its mission at NATO, shuts alliance’s office”. AP. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Chernova, Anna; Fox, Kara. “Russia suspending mission to NATO in response to staff expulsions”. CNN. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Madrid Summit ends with far-reaching decisions to transform NATO”. NATO. 30 June 2022.

- ^ Wolska, Anna (15 July 2023). “Fake of the week: Russia is waging war against NATO in Ukraine”. EURACTIV.pl.

- ^ “”Special military operation”, “Nazis” and “at war with NATO”: Russian state media framing of the Ukraine war”. ISPI. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Vavra, Shannon (21 September 2022). “‘The Time Has Come’: Top Putin Official Admits Ugly Truth About War”. The Daily Beast. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Tisdall, Simon (5 March 2023). “Nato faces an all-out fight with Putin. It must stop pulling its punches”. The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Sarotte, Mary Elise (2014). “A Broken Promise? What the West Really Told Moscow About NATO Expansion”. Foreign Affairs. 93 (5): 90–97. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 24483307.

- ^ Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: Scholarly debates, policy implications, and roads not taken Evaluating NATO Enlargement: From Cold War Victory to the Russia-Ukraine War: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 1-42 doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7_1.

- ^ Zollmann, Florian (30 December 2023). “A war foretold: How Western mainstream news media omitted NATO eastward expansion as a contributing factor to Russia’s 2022 invasion of the Ukraine”. Media, War & Conflict. 17 (3): 373–392. doi:10.1177/17506352231216908. ISSN 1750-6352. This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Korshunov, Maxim (16 October 2014). “Mikhail Gorbachev: I am against all walls”. rbth.com. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: From cold war victory to the Russia-Ukraine war: Springer International Publishing; 2023. 1-645 p doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7.

- ^ “Old adversaries become new partners”. NATO.

- ^ Iulian, Raluca Iulia (23 August 2017). “A Quarter Century of Nato-Russia Relations”. Cbu International Conference Proceedings. 5: 633–638. doi:10.12955/cbup.v5.998. ISSN 1805-9961.

- ^ “First NATO Secretary General in Russia”. NATO.

- ^ “NATO’s Relations With Russia”. NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Belgium. 6 April 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ “NATO Strategic Concept for the Defence and Security of the Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization” (PDF). NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Belgium. 20 November 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ “The NATO-Russia Archive – Formal NATO-Russia Relations”. Berlin Information-Center For Translantic Security (BITS), Germany. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ “NATO PfP Signatures by Date”. NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Belgium. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Kozyrev, Andrei (2019). “Russia and NATO Enlargement: An Insider’s Account” (PDF).

- ^ Whitney, Craig R. (9 November 1995). “Russia Agrees To Put Troops Under U.S., Not NATO”. New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015.

- ^ Jones, James L. (3 July 2003). “Peacekeeping: Achievements and Next Steps”. NATO.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Lessons and Conclusions on the Execution of IFOR Operations and Prospects for a Future Combined Security System: The Peace and Stability of Europe after IFOR” (PDF). Foreign Military Studies Office. November 2000. p. 4.

- ^ Shevtsov, Leonty (21 June 1997). “Russian Participation in Bosnia-Herzegovina”.

- ^ Joulwan, George (21 June 1997). “The New NATO: The Way Ahead”.

I firmly believe that our cooperation at SHAPE and in Bosnia was instrumental in the creation of the NATO-Russia Founding Act, which was signed in May 1997 in Paris. As NATO’s Deputy Secretary General said, ‘Political reality is finally catching up with the progress you at SHAPE had already made.’

- ^ Ronald D. Azmus, Opening NATO’s Door (2002) p. 210.

- ^ Strobe Talbott, The Russia Hand: A Memoir of Presidential Diplomacy (2002) p. 246.

- ^ Fergus Carr and Paul Flenley, “NATO and the Russian Federation in the new Europe: the Founding Act on Mutual Relations.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 15.2 (1999): 88–110.

- ^ “5/15/97 Fact Sheet: NATO-Russia Founding Act”. 1997-2001.state.gov. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “NATO Publications”. www.nato.int. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ “Nato-Russia Council – Documents & Glossaries”. www.nato.int. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ The NATO-Russia Joint Editorial Working Group (8 June 2021). “NATO-Russia Glossary of Contemporary Political and Military Terms” (PDF).

- ^ “Yeltsin: Russia will not use force against Nato”. The Guardian. 25 March 1999.

- ^ “Yeltsin warns of possible world war over Kosovo”. CNN. 9 April 1999.

- ^ Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: From cold war victory to the Russia-Ukraine war: Springer International Publishing; 2023. 1-645 p doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7. p.165.

- ^ “Russia Condemns NATO’s Airstrikes”. Associated Press. 8 June 1999.

- ^ Jackson, Mike (2007). Soldier. Transworld Publishers. pp. 216–254. ISBN 9780593059074.

- ^ “Confrontation over Pristina airport”. BBC News. 9 March 2000.

- ^ Peck, Tom (15 November 2010). “Singer James Blunt ‘prevented World War 3′”. Belfast Telegraph.

- ^ Hall, Todd (September 2012). “Sympathetic States: Explaining the Russian and Chinese Responses September 11”. Political Science Quarterly. 127 (3): 369–400. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2012.tb00731.x.

- ^ “NATO–Russia Council Statement 28 May 2002” (PDF). NATO. 28 May 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Nato-Russia Council – About”. www.nato.int. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ NATO. “NATO – Official text: Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation signed in Paris, France, 27-May.-1997”. NATO. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Cook, Lorne (25 May 2017). “NATO: The World’s Largest Military Alliance Explained”. www.MilitaryTimes.com. The Associated Press, US. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ “Structure of the NATO-Russia Council” (PDF). Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ “Nato Blog | Dating Council”. www.nato-russia-council.info. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009.

- ^ “Nat-o Blog | Dating Council”. www.nato-russia-council.info.

- ^ “Nato Blog | Dating Council”. www.nato-russia-council.info. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009.

- ^ “Allies and Russia attend U.S. Nuclear Weapons Accident Exercise”. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ “NATO Summit Meetings – Rome, Italy – 28 May 2002”. www.nato.int. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Ukraine News The Chronicles of War (24 June 2022). путин о вступлении Украины в НАТО. Retrieved 26 October 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Zwack, Peter B. (Spring 2004). “A NATO-Russia Contingency Command”. Parameters: 89.

- ^ Guinness World Records: First murder by radiation:

On 23 November 2006, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Litvinenko, a retired member of the Russian security services (FSB), died from radiation poisoning in London, UK, becoming the first known victim of lethal Polonium 210-induced acute radiation syndrome. - ^ “CPS names second suspect in Alexander Litvinenko poisoning”. The Telegraph. 29 February 2012. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Chapter 2. Rights and Freedoms of Man And Citizen | The Constitution of the Russian Federation. Constitution.ru. Retrieved on 12 August 2013.

- ^ “Russia warns of resorting to ‘force’ over Kosovo”. France 24. 22 February 2008.

- ^ In quotes: Kosovo reaction, BBC News Online, 17 February 2008.

- ^ “Putin calls Kosovo independence ‘terrible precedent'”. The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 February 2008.

- ^ “NATO’s relations with Russia”.

- ^ “Ukraine: NATO’s original sin”. Politico. 23 November 2021.

- ^ Menon, Rajan (10 February 2022). “The Strategic Blunder That Led to Today’s Conflict in Ukraine”. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ Bush backs Ukraine on Nato bid, BBC News (1 April 2008)

- ^ Ukraine Says ‘No’ to NATO, Pew Research Center (29 March 2010)

- ^ “Medvedev warns on Nato expansion”. BBC News. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ “Bush stirs controversy over NATO membership”. CNN. 1 April 2008.

- ^ “NATO Press Release (2008)108 – 27 Aug 2008”. Nato.int. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ “NATO Press Release (2008)107 – 26 Aug 2008”. Nato.int. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Pop, Valentina (1 April 2009). “Russia does not rule out future NATO membership”. EUobserver. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ “Nato-Russia relations plummet amid spying, Georgia rows”. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ “Военные считают ПРО в Европе прямой угрозой России – Мир – Правда.Ру”. Pravda.ru. 22 August 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Q&A: US missile defence”. BBC News. 20 September 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ NATO chief asks for Russian help in Afghanistan Reuters Retrieved on 9 March 2010

- ^ Angela Stent, The Limits of Partnership: U.S.-Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century (2014) pp 230–232.

- ^ “Medvedev: August War Stopped Georgia’s NATO Membership”. Civil Georgia. 21 November 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ “Russian and Nato jets to hold first ever joint exercise”. Telegraph. 1 June 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ “Nato rejects Russian claims of Libya mission creep”. The Guardian. 15 April 2011.

- ^ “West in “medieval crusade” on Gaddafi: Putin Archived 23 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine.” The Times (Reuters). 21 March 2011.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (21 April 2012). “Russians Protest Plan for NATO Site in Ulyanovsk”. The New York Times.

- ^ “NATO warns Russia to cease and desist in Ukraine”. Euronews.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ “Ukraine Crisis: NATO Suspends Russia Co-operation”. BBC News, UK. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Statement by NATO Foreign Ministers – 1 April 2014”. NATO.

- ^ “Address by President of the Russian Federation”. President of Russia.

- ^ “Why the Kosovo “precedent” does not justify Russia’s annexation of Crimea”. Washington Post.

- ^ Lars Molteberg Glomnes (25 March 2014). “Stoltenberg med hard Russland-kritikk” [Stoltenberg was met with fierce criticism from Russia]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 March 2014.

- ^ “Stoltenberg: – Russlands annektering er en brutal påminnelse om Natos viktighet” [Stoltenberg: – Russia’s annexation is a brutal reminder of the importance of NATO]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 28 March 2014. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014.

- ^ Tron Strand, Anders Haga; Kjersti Kvile, Lars Kvamme (28 March 2014). “Stoltenberg frykter russiske raketter” [Stoltenberg fears of Russian missiles]. Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 31 March 2014.

- ^ “NATO-Russia Relations: The Background” (PDF). NATO. March 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Joint Statement of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, 4 September 2014.

- ^ Joint statement of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, 2 December 2014.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (9 November 2014). “Close military encounters between Russia and the west ‘at cold war levels'”. The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ “Russia Baltic military actions ‘unprecedented’ – Poland”. UK: BBC News. 28 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ “Four RAF Typhoon jets head for Lithuania deployment”. UK: BBC News. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ “U.S. asks Vietnam to stop helping Russian bomber flights”. Reuters. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ “Russian Strategic Bombers To Continue Patrolling Missions”. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Schwartz, Paul N. (16 October 2014). “Russian INF Treaty Violations: Assessment and Response”. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gordon, Michael R. (28 July 2014). “U.S. Says Russia Tested Cruise Missile, Violating Treaty”. The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ “US and Russia in danger of returning to era of nuclear rivalry”. The Guardian. UK. 4 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R. (5 June 2015). “U.S. Says Russia Failed to Correct Violation of Landmark 1987 Arms Control Deal”. The New York Times. US. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Bodner, Matthew (3 October 2014). “Russia Overtakes U.S. in Nuclear Warhead Deployment”. The Moscow Times. Moscow. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ The Trillion Dollar Nuclear Triad Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies: Monterey, CA. January 2014.

- ^ Broad, William J.; Sanger, David E. (21 September 2014). “U.S. Ramping Up Major Renewal in Nuclear Arms”. The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ “Russian military attack on the Czech territory: details, implications and next steps” (PDF). Kremlin Watch Report. 21 April 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2021. Alt URL

- ^ Kramář, Rudolf (14 October 2020). “Zásah ve Vrběticích je po dlouhých letech ukončen” [The intervention in Vrbětice is over after many years]. hzscr.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ “Czechia expels Russian diplomats over 2014 ammunition depot blast”. Al Jazeera English. 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Eckel, Mike; Bedrov, Ivan; Komarova, Olha (18 April 2021). “A Czech Explosion, Russian Agents, A Bulgarian Arms Dealer: The Recipe For A Major Spy Scandal In Central Europe”. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Pavel, Petr (29 April 2024). “Czech president April 29th 2024 tweet on the 2014 ammunition depot explosion”.

- ^ Statement of Foreign Ministers on the Readiness Action Plan NATO, 02 Dec 2014.

- ^ “NATO condemns Russia, supports Ukraine, agrees to rapid-reaction force”. New Europe. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ “Nato shows its sharp end in Polish war games”. Financial Times. UK. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ “Nato testing new rapid reaction force for first time”. UK: BBC News. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ “Russia’s New Military Doctrine Hypes NATO Threat”. 30 December 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Putin signs new military doctrine naming NATO as Russia’s top military threat National Post, December 26, 2014.

- ^ “NATO Head Says Russian Anti-Terror Cooperation Important“. Bloomberg. 8 January 2015

- ^ “Insight – Russia’s nuclear strategy raises concerns in NATO”. Reuters. 4 February 2015. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Croft, Adrian (6 February 2015). “Supplying weapons to Ukraine would escalate conflict: Fallon”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Press Association (19 February 2015). “Russia a threat to Baltic states after Ukraine conflict, warns Michael Fallon”. The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ А.Ю.Мазура (10 March 2015). “Заявление руководителя Делегации Российской Федерации на переговорах в Вене по вопросам военной безопасности и контроля над вооружениями”. RF Foreign Ministry website.

- ^ Grove, Thomas (10 March 2015). “Russia says halts activity in European security treaty group”. Reuters. UK. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Aksenov, Pavel (24 July 2015). “Why would Russia deploy bombers in Crimea?”. London: BBC. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ “From Russia with Menace”. The Times. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (1 April 2015). “Norway Reverts to Cold War Mode as Russian Air Patrols Spike”. The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ New York Times: How a Poisoning in Bulgaria Exposed Russian Assassins in Europe

- ^ Euractiv: Bulgaria seeks extradition of three spies from Russia in Novichok case

- ^ Financial Times: Russian hitmen and saboteurs target Bulgaria’s arms industry, magnate says

- ^ Jump up to:a b MacFarquhar, Neil, “As Vladimir Putin Talks More Missiles and Might, Cost Tells Another Story”, New York Times, June 16, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ Not a single Russia-NATO cooperation program works — Russian diplomat TASS, 16 June 2015.

- ^ “US announces new tank and artillery deployment in Europe”. UK: BBC. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ “NATO shifts strategy in Europe to deal with Russia threat”. UK: FT. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Putin says Russia beefing up nuclear arsenal, NATO denounces ‘saber-rattling'”. Reuters. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Комментарий Департамента информации и печати МИД России по итогам встречи министров обороны стран-членов НАТО the RF Foreign Ministry, 26 June 2015.

- ^ Steven Pifer, Fiona Hill. “Putin’s Risky Game of Chicken”, New York Times, June 15, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ Steven Pifer. Putin’s nuclear saber-rattling: What is he compensating for? 17 June 2015.

- ^ “Russian Program to Build World’s Biggest Intercontinental Missile Delayed”. The Moscow Times. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ telegraph.co.uk: “US confirms it will place 250 tanks in eastern Europe to counter Russian threat”, 23 Jun 2015

- ^ telegraph.co.uk: “Nato updates Cold War playbook as Putin vows to build nuclear stockpile”, 25 Jun 2015

- ^ “NATO ‘very concerned’ by Russian military build-up in Crimea”. Hurriyet Daily News. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ “NATO-Russia Tensions Rise After Turkey Downs Jet”. The New York Times. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ “Turkey’s downing of Russian warplane – what we know”. BBC. 24 November 2015.

- ^ “ATO Invites Montenegro to Join, as Russia Plots Response”. The New York Times. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ “Crimea”. Interfax-Ukraine. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ НАТО созрело для диалога с Москвой Nezavisimaya gazeta, 14 April 2016.

- ^ “TASS: Russian Politics & Diplomacy – Lavrov: Russia will not allow NATO to embroil it into senseless confrontation”. TASS. 14 April 2016.

- ^ “Лавров: РФ не даст НАТО втянуть себя в бессмысленное противостояние”. РИА Новости. 14 April 2016.

- ^ “Turkish Request for Missiles Strains Ties With Russia – Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East”. Al-Monitor. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Грушко: позитивной повестки дня у России и НАТО сейчас нет RIA Novosti, 20 April 2016.

- ^ Nato-Russia Council talks fail to iron out differences The Guardian, 20 April 2016.

- ^ “U.S. launches long-awaited European missile defense shield”. CNN politics. 12 May 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ “Russia Calls New U.S. Missile Defense System a ‘Direct Threat'”. The New York Times. 12 May 2016.

- ^ Levada-Center and Chicago Council on Global Affairs about Russian-American relations Archived 19 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Levada-Center. 4 November 2016.

- ^ NATO agrees to reinforce eastern Poland, Baltic states against Russia Reuters, 8 July 2016.

- ^ Warsaw Summit Communiqué See para 40.

- ^ Warsaw Summit Communiqué See para 11.

- ^ Warsaw Summit Communiqué See para 17.

- ^ Warsaw Summit Communiqué See para 10.

- ^ “NATO leaders confirm strong support for Ukraine”. NATO.

- ^ Москва предупредила НАТО о последствиях военной активности в Черном море

- ^ “Russia offers to fly warplanes more safely over Baltics”. Reuters. 14 July 2016. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016.

- ^ «Триумф» в Крыму Gazeta.ru, 17 July 2016.

- ^ Bajrović, Reuf; Garčević, Vesko; Kramer, Richard. “Hanging by a Thread: Russia’s Policy of Destabilization in Montenegro” (PDF). Foreign Policy Research Institute.

- ^ “Sve o aferi državni udar”.

- ^ “U Crnoj Gori nastavljeno suđenje za državni udar”. Al Jazeera (September 2017).

- ^ Ukinuta presuda za ‘državni udar’ u Crnoj Gori, DPS tvrdi rezultat pritiska na sud, Slobodna Evropa, 5 February 2021

- ^ “How the use of ethnonationalism backfired in Montenegro”. Al-Jazeera. 4 September 2020.

- ^ Montenegro finds itself at heart of tensions with Russia as it joins Nato: Alliance that bombed country only 18 years ago welcomes it as 29th member in move that has left its citizens divided The Guardian, 25 May 2017.

- ^ В Брюсселе подписан протокол о вступлении Черногории в НАТО Парламентская газета, 19 May 2016.

- ^ “Об обращении Государственной Думы Федерального Собрания Российской Федерации “К парламентариям государств – членов Организации Североатлантического договора, Парламентской ассамблеи Организации по безопасности и сотрудничеству в Европе, Народной скупщины Республики Сербии, Скупщины Черногории, Парламентской Ассамблеи Боснии и Герцеговины, Собрания Республики Македонии”, Постановление Государственной Думы от 22 июня 2016 года №9407-6 ГД, Обращение Государственной Думы от 22 июня 2016 года №9407-6 ГД”. docs.cntd.ru. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ John McCain: Russia threat is dead serious. Montenegro coup and murder plot proves it. USA Today, 29 June 2017.

- ^ Former Montenegrin PM Says Russia Wants To Destroy EU Radio Liberty, 14 March 2017.

- ^ Russians, opposition figures sentenced over role in 2016 Montenegro coup attempt. Reuters, 9 May 2019.

- ^ Доброхотов, Роман (24 March 2017). “Кремлевский спрут. Часть 2. Как ГРУ пыталось организовать переворот в Черногории”. The Insider (in Russian).

- ^ Организаторы переворота в Черногории участвовали в аннексии Крыма – СМИ Корреспондент.net, 21 November 2016.

- ^ “Attempted coup in Montenegro in 2016: Foreign Secretary’s statement”. 9 May 2019.

- ^ “Lavrov Says Russia Wants Military Cooperation With NATO, ‘Pragmatic’ U.S. Ties”. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 18 February 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Julian E., “Russian, NATO Diplomats Discuss Military Deployments in Baltic Sea Region” (subscription required), The Wall Street Journal, 30 March 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- ^ Press point by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg following the meeting of the NATO-Russia Council nato.int, 13 July 2013.

- ^ Russia tells NATO to stop ‘demonising’ planned war games Reuters, 13 July 2017.

- ^ NATO battlegroups in Baltic nations and Poland fully operational nato.int, 28 August 2017.

- ^ “Russia was the target of Nato’s own fake news”. The Independent. 22 September 2017.

- ^ “NATO sees no Russian threat to any of its members — head”. TASS. 21 February 2018.

- ^ “The Latest: Gorbachev has high hopes for Putin-Trump summit”. Associated Press. 28 June 2018.

- ^ “NATO chief warns against isolating Russia”. Euronews. 12 July 2018.

- ^ “Nato slashes Russia staff after poisoning”. BBC News. 27 March 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Harding, Luke (23 June 2020). “A chain of stupidity’: the Skripal case and the decline of Russia’s spy agencies”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ AFP (5 October 2018). “Russian military intelligence’s embarrassing blunders”. France 24. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ Sébastian, Seibt (20 April 2021). “Unit 29155, the Russian spies specialising in ‘sabotage and assassinations'”. France 24. Archived from the original on 26 August 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Sanger, David E.; Broad, William J. (19 October 2019). “U.S. to Tell Russia It Is Leaving Landmark I.N.F. Treaty”. The New York Times. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (20 October 2018). “Trump says US will withdraw from nuclear arms treaty with Russia”. The Guardian. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ “What the INF Treaty’s Collapse Means for Nuclear Proliferation”. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ “9M729 (SSC-8)”. Missile Threat. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ Borger, Julian (2 October 2018). “US Nato envoy’s threat to Russia: stop developing missile or we’ll ‘take it out'”. Guardian News & Media Limited.

- ^ “President Trump to pull US from Russia missile treaty”. BBC. 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ “Trump: U.S. to exit nuclear treaty, citing Russian violations”. Reuters. 20 October 2019.

- ^ “Pompeo announces suspension of nuclear arms treaty”. CNN. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty at a Glance, Arms Control Association, August 2019.

- ^ “INF nuclear treaty: US pulls out of Cold War-era pact with Russia”. BBC News. 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ “NATO chief warns of Russia threat, urges unity in U.S. address”. Reuters. 3 April 2019.

- ^ “NATO chief calls for confronting Russia in speech to Congress”. Politico. 3 April 2019.

- ^ “Suspected Assassin In The Berlin Killing Used Fake Identity Documents”. Bellingcat. 30 August 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Eckel, Mike (28 August 2019). “Former Chechen Commander Gunned Down In Berlin; Eyes Turn To Moscow (And Grozny)”. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ “Germany expels Russian diplomats over state-ordered killing”. AP NEWS. 15 December 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ “Chechen leader ‘was behind Berlin assassination’ of Zelimkhan Khangoshvili”. The Times. 6 December 2019.

- ^ “New Evidence Links Russian State to Berlin Assassination”. Bellingcat. 27 September 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ “Lavrov: If Georgia Joins NATO, Relations Will Be Spoiled”. Georgia Today. 26 September 2019.

- ^ “Russian FM Lavrov supports resumption of flights to Georgia as Georgians ‘realised consequences’ of June 20”. Agenda.ge. 26 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ Sabbagh, Dan; Roth, Andrew (13 April 2021). “Nato tells Russia to stop military buildup around Ukraine”. The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ “NATO warns Russia over forces near Ukraine”. Al Jazeera. 13 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Germany Says Russia Seeking To ‘Provoke’ With Troop Buildup At Ukraine’s Border”. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 14 April 2021.

- ^ “Massive, Army-led NATO exercise Defender Europe kicks off”. Army Times. 15 March 2021.

- ^ “NATO expels eight Russian ‘undeclared intelligence officers’ in response to suspected killings and espionage”.

- ^ “Russia will act if Nato countries cross Ukraine ‘red lines’, Putin says”. The Guardian. 30 November 2021.

- ^ “NATO Pushes Back Against Russian President Putin’s ‘Red Lines’ Over Ukraine”. The Drive. 1 December 2021.

- ^ “Putin warns Russia will act if NATO crosses its red lines in Ukraine”. Reuters. 30 November 2021.

- ^ Blinken, Antony (20 January 2022). “Speech: The Stakes of Russian Aggression for Ukraine and Beyond”. US Department of State.

- ^ “Putin Demands NATO Guarantees Not to Expand Eastward”. U.S. News & World Report. 1 December 2021.

- ^ “NATO chief: “Russia has no right to establish a sphere of influence””. Axios. 1 December 2021.

- ^ “Is Russia preparing to invade Ukraine? And other questions”. BBC News. 10 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Tétrault-Farber, Gabrielle; Balmforth, Tom (17 December 2021). “Russia demands NATO roll back from East Europe and stay out of Ukraine”. Reuters. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ “U.S. to consider Russia’s NATO proposal, but calls some demands “unacceptable””. Axios. 17 December 2021.

- ^ Pifer, Steven (21 December 2021). “Russia’s draft agreements with NATO and the United States: Intended for rejection?”. Brookings Institution.

- ^ “Ukraine crisis: Why Russia-US talks may prove crucial”. BBC News. 10 January 2022.

- ^ “Russian foreign minister warns west over ‘aggressive line’ in Ukraine crisis”. The Guardian. 31 December 2021.

- ^ “Russia-NATO Council ends Brussels meeting that lasted four hours”. TASS. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Emmott, Robin; Siebold, Sabine; Baczynska, Gabriela (12 January 2022). “NATO offers arms talks as Russia warns of dangers”. Reuters. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ “US offers no concessions in response to Russia on Ukraine”. Associated Press. 26 January 2022.

- ^ “NATO says Russia appears to be continuing military escalation in Ukraine”. France 24. France 24. 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ “Extracts from Putin’s speech on Ukraine”. Reuters. 21 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2 December 2023.

- ^ “NATO leaders will boost 4 new battalions in the east in the face of Russian threat”. Infobae. 23 March 2022.

- ^ “Rusya’dan İsveç ve Finlandiya’ya tehdit”. www.yenisafak.com (in Turkish). 26 February 2022.

- ^ “Путин заявил, что вступление Финляндии и Швеции в НАТО не создает угрозы”. RBC (in Russian). 16 May 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ “NATO brands Russia the biggest ‘direct threat’ to Western security, as it eyes off ‘serious challenges’ posed by China”. ABC News. 30 June 2022.

- ^ Topic: NATO-Russia Council

- ^ WHY NATO-RUSSIA COUNCIL HAS FAILED AFTER 20 YEARS OF EXISTENCE

- ^ Hirsh, Michael (27 June 2022). “We Are Now in a Global Cold War”. Foreign Policy.

- ^ Kanta Ray, Rajat; Guha, Dipanjan. “The second Cold War: Editorial on Russia’s Ukraine invasion”. The Telegraph.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Weakness is Lethal: Why Putin Invaded Ukraine and How the War Must End”. Institute for the Study of War. 1 October 2023.

- ^ “Former Russian president Medvedev says Moscow should seek ‘disappearance’ of Ukraine and NATO”. Reuters. 11 July 2024.

- ^ “Putin warns the US of Cold War-style missile crisis”. Reuters. 28 July 2024.

- ^ Pleitgen, Frederik; Lillis, Katie Bo; Bertrand, Natasha (11 July 2024). “Exclusive: US and Germany foiled Russian plot to assassinate CEO of arms manufacturer sending weapons to Ukraine | CNN Politics”. CNN. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (11 July 2024). “US reportedly foiled Russian plot to kill boss of German arms firm supplying Ukraine”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

- ^ Siebold, Sabine (14 October 2024). “NATO will not be intimidated by Russia’s threats, Rutte says at Ukraine mission HQ”. Reuters. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Rothwell, James; Crisp, James (16 October 2024). “Russia ‘suspected of planting bomb’ on plane to the UK”. The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ “Subscribe to read”. www.ft.com. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ “DHL confirms parcels linked to arson attack in Germany sent from Lithuania”. lrt.lt. 3 September 2024. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ Panyi, Szabolcs (15 October 2024). “Russian Diplomats with GRU Ties: Hungary’s Special Guests”. VSquare.org. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ Wewnętrznego, Agencja Bezpieczeństwa. “Komunikat dotyczący działalności dywersyjnej FR”. Agencja Bezpieczeństwa Wewnętrznego (in Polish). Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ Gielewska, Anna (30 October 2024). “Mapping Russia’s War Machine on NATO’s Doorstep”. VSquare.org. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Robert Coalson: Could NATO Membership For Russia Break Impasse In European Security Debate?, 5 February 2010.

- ^ “A Broken Promise?”. Foreign Affairs. October 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ “SOVIET DISARRAY; Yeltsin Says Russia Seeks to Join NATO”. The New York Times. 21 December 1991. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ^ Baker, James (5 December 1993). “Expanding to the East: A New NATO: Alliance: Full membership may be the most sought-after ‘good’ now enticing Eastern and Central European states–particularly, Russia”. Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Brown, Davis L. (1997). “European Collective Security in the Next Millennium” (PDF). The Air Force Law Review, volume 42.

- ^ Putin suggested Russia joining NATO to Clinton. The Hindu. Published 12 June 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Breaking Down the Complicated Relationship Between Russia and NATO”. TIME. 4 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Ex-Nato head says Putin wanted to join alliance early on in his rule”. The Guardian. 4 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Former Nato chief says Putin considered membership for Russia | BBC News, retrieved 23 February 2024

- ^ “Ex-Nato head says Putin wanted to join alliance early on in his rule”. The Guardian. 4 November 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Anna Politkovskaya Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ World Politics Review, “Politkovskaya’s Death, Other Killings, Raise Questions About Russian Democracy”, 31 October 2006

- ^ Gilman, Martin (16 June 2009). “Russia Leads Europe In Reporter Killings”. Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ The State of the World’s Human Rights (Internet Archive), Amnesty International 2009, Report on Jan–Dec 2008, p. 272: “In June [2008], the Office of the Prosecutor General announced that it had finished its investigation into the killing of human rights journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who was shot dead in Moscow in October 2006. Three men accused of involvement in her murder went on trial in November; all denied the charges. A fourth detainee, a former member of the Federal Security Services who had initially been detained in connection with the murder, remained in detention on suspicion of another crime. The person suspected of shooting Anna Politkovskaya had not been detained by the end of the year and was believed to be in hiding abroad.”

- ^ “Anna Politkovskaya: Putin’s Russia”. BBC News. 9 October 2006. Archived from the original on 7 November 2006. Retrieved 9 October 2006.

- ^ “How Bill Browder Became Russia’s Most Wanted Man”. The New Yorker. 13 August 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ “Russia ‘is now a criminal state’, says Bill Browder”. BBC. 23 November 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ Browder, Bill (2015). Red Notice: How I Became Putin’s No. 1 Enemy. Transworld Digital. ISBN 978-0593072950.

- ^ Lombardozzi, Nicola (20 November 2014). “I quaderni del carcere di chi sfidò lo zar Putin”. la Repubblica (in Italian). p. 53.

- ^ Ex-minister wants to bring Russia into NATO Der Spiegel Retrieved on 9 March 2010

- ^ “Russia outlines plan for ‘unfriendly’ investors to sell up at half-price”. Reuters. 30 December 2022.

- ^ Neyfakh, Leon (9 March 2014). “Putin’s long game? Meet the Eurasian Union”. Boston Globe. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rohde, David; Mohammed, Arshad (18 April 2014). “Special Report: How the U.S. made its Putin problem worse”. Reuters. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ “Russia Redefines Itself and Its Relations with the West”, by Dmitri Trenin, The Washington Quarterly, Spring 2007

- ^ Buckley, Neil (19 September 2013). “Putin urges Russians to return to values of religion”. Financial Times. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Hoare, Liam (26 December 2014). “Europe’s New Gay Cold War”. Slate. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David (11 August 2013). “Gays in Russia Find No Haven, Despite Support From the West”. The New York Times. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ Matlack, Carol (4 June 2014). “Does Russia’s Global Media Empire Distort the News? You Be the Judge”. Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Spiegel Staff (30 May 2014). “The Opinion-Makers: How Russia Is Winning the Propaganda War”. Der Spiegel. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Tetrault-Farber, Gabrielle (12 May 2014). “Poll Finds 94% of Russians Depend on State TV for Ukraine Coverage”. The Moscow Times. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Remnick, David (11 August 2014). “Watching the Eclipse”. The New Yorker. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Kruscheva, Nina (29 July 2014). “Putin’s anti-American rhetoric now persuades his harshest critics”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Lally, Kathy (10 April 2014). “Moscow turns off Voice of America radio”. Washington Post. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ “A clampdown on foreign-owned media is an opportunity for some oligarchs”. The Economist. 8 November 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ “Four EU Countries Propose Steps to Counter Russia’s Propaganda”. Bloomberg. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ “Mogherini: EU may establish Russian-language media”. Reuters. 19 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Vasiliev, Nikita (28 February 2015). “Круглосуточная камера зафиксировала убийство Немцова” [CCTV recorded murder of Nemtsov] (in Russian). Moscow. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Amos, Howard; Millward, David (27 February 2015). “Leading Putin critic gunned down outside Kremlin”. The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ “Russia opposition politician Boris Nemtsov shot dead”. BBC News. 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ “Борис Немцов: Боюсь того, что Путин меня убьет”. Sobesednik. 10 February 2015. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Russia opposition politician Boris Nemtsov shot dead”. BBC News. 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ Calamur, Krishnadev (27 February 2015). “Putin Critic Boris Nemtsov Shot Dead”. NPR. Archived from the original on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ Собчак: Немцов собирался опубликовать доклад об участии российских военных в войне на Украине (in Russian). RosBalt. 28 February 2015. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ В квартире Немцова проводится обыск [A search is going on in Nemtsov’s flat] (in Russian). Russia: RBK. 28 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ Shaun Walker (8 March 2015) Boris Nemtsov murder: Chechen chief Kadyrov confirms link to prime suspect Archived 22 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian

- ^ “Boris Nemtsov Tailed by FSB Squad Prior to 2015 Murder”. Bellingcat. 28 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew (28 February 2015). “Fear Envelops Russia After Killing of Putin Critic Boris Nemtsov”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ Ioffe, Julia (28 February 2015). “After Boris Nemtsov’s Assassination, ‘There Are No Longer Any Limits'”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ “Breaking Down the Complicated Relationship Between Russia and NATO”. Time. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Kimberly Marten, “NATO enlargement: evaluating its consequences in Russia.” International Politics 57 (2020): 401-426.

- ^ For similar critiques see James Goldgeier, and Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson, “Evaluating NATO enlargement: scholarly debates, policy implications, and roads not taken.” International Politics 57 (2020): 291-321.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Godzimirski, Jakub M. (2019). “Explaining Russian reactions to increased NATO military presence”. Norsk Utenrikspolitisk Institutt. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ “Umowa między Rządem Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej i Rządem Federacji Rosyjskiej o żegludze po Zalewie Wiślanym (Kaliningradskij zaliw), podpisana w Sopocie dnia 1 września 2009 r.” isap.sejm.gov.pl.

- ^ “Co zmieni kanał na Mierzei Wiślanej?”. 24 February 2007. Archived from the original on 24 February 2007.

- ^ Finn, Peter (3 November 2007). “Russia’s State-Controlled Gas Firm Announces Plan to Double Price for Georgia”. Washington Post. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Russia gets tough on energy sales to Europe: No foreign access to pipelines, official says, by Judy Dempsey, International Herald Tribune 12 December 2006

- ^ “Arbitration Panel Holds That the 1994 Energy Charter Treaty Protects Foreign Energy Sector Investments in Former Soviet Union”. Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. 5 February 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ “Putin’s ‘Last and Best Weapon’ Against Europe: Gas”. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Klapper, Bradley (3 February 2015). “New Cold War: US, Russia fight over Europe’s energy future”. Yahoo. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Stewart, James (7 March 2014). “Why Russia Can’t Afford Another Cold War”. The New York Times. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Albanese, Chiara; Edwards, Ben (9 October 2014). “Russian Companies Clamor for Dollars to Repay Debt”. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Chung, Frank (18 December 2014). “The Cold War is back, and colder”. News.au. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2014.