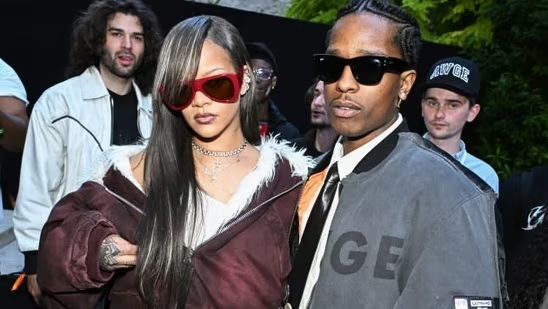

In February, lightning struck twice at the Berlin International Film Festival as the normally arthouse-focused event showcased the world premieres of two major commercial South Korean films: the occult drama Exhuma and the action-packed The Roundup: Punishment. Both films have drawn considerable attention not only for their commercial potential but also for their bold narratives, marking a significant departure from the festival’s typical fare, which leans toward more experimental and niche works. These premieres highlight the growing influence of South Korea’s film industry, which is increasingly breaking out of its traditionally arthouse mold and resonating with global audiences.

Exhuma, an occult thriller, and The Roundup: Punishment, a high-octane action film, represent the latest wave of South Korean cinema’s appeal to international markets. While the country’s film industry has historically been known for its art-house films and deeply emotional dramas, this shift to more mainstream, genre-driven content signifies a broader transformation, with South Korean cinema gaining even more prominence on the world stage.

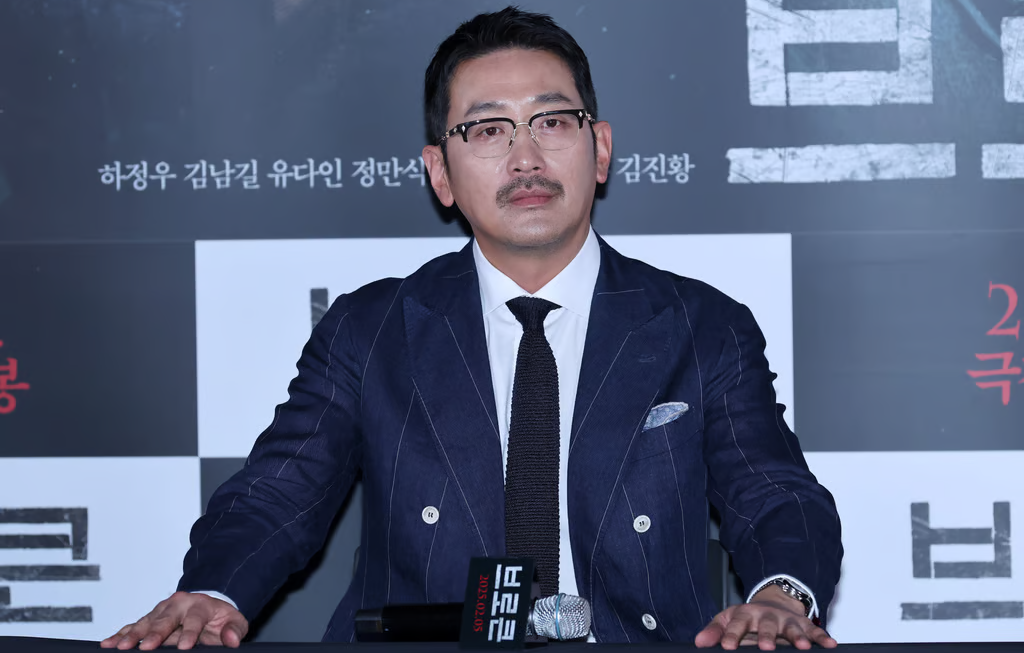

Looking ahead to the 2024 Cannes Film Festival, South Korea could once again make waves with the anticipated release of I, the Executioner (aka Veteran 2), directed by Ryoo Seung-wan. The film is a sequel to Veteran (2015), a crime thriller that not only became a massive hit in South Korea but also caught the attention of Hollywood, with director Michael Mann expressing interest in remaking it. Veteran was a fast-paced, action-packed film that blended social commentary with intense drama, and many are eager to see if its follow-up can match or exceed its predecessor’s success.

However, despite the buzz around I, the Executioner, the film’s selection for a Midnight Screening slot in Cannes’ official program marks a contrast to the dominant presence South Korean cinema enjoyed in the past. The golden years of South Korean cinema at Cannes saw high-profile triumphs like Parasite, which won the Palme d’Or in 2019 and went on to become a global cultural touchstone. Since then, the representation of Korean films in the official selection has declined, and I, the Executioner’s position in the Midnight Screening section indicates that the competition is stiffer than ever.

While the South Korean film industry has proven its resilience and versatility, the diminished presence in Cannes this year may suggest a shift in global tastes and competition, or perhaps a signal that the Korean film scene is exploring new avenues beyond the festival circuit. Nevertheless, the international anticipation for I, the Executioner and the recent Berlin festival premieres underscore the continued global interest in South Korean cinema and its ever-evolving landscape. The future remains bright for the industry, even if it faces new challenges and uncertainties.

Korean cinema, once a filmmaking powerhouse renowned for its versatility across genres, registers, and scales, finds itself grappling with a difficult struggle to regain its footing in the post-pandemic era. The origins of this decline are the subject of much debate, but several key factors are often highlighted as contributing to the industry’s challenges.

One major issue that has hampered the South Korean film industry’s recovery is the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic caused significant disruptions in production schedules, delayed releases, and altered the way films were marketed and distributed. Cinemas were forced to close for extended periods, and even as theaters reopened, the audience’s return to in-person screenings was slow. With restrictions on large gatherings, many films faced limited theatrical runs, and the economic downturn put additional pressure on the industry.

Beyond the pandemic, high cinema ticket prices have become another point of contention. The rising costs of attending films have caused some audiences to reconsider whether it’s worth the expense, especially with the convenience of streaming platforms offering a more affordable alternative. As a result, theaters, especially those that were already struggling, have faced lower attendance rates, further pushing the industry into a financial pit. The challenge has been compounded by the fact that many audiences are opting to stay home and watch films on streaming platforms instead, lured by the easy access and vast catalog of movies.

Furthermore, the increasing dominance of streaming services like Netflix, which has heavily invested in South Korean content, has played a pivotal role in this shift. While streaming platforms have provided an alternative outlet for films, they have also siphoned off critical resources from the traditional film production pipeline. Production crews, key talent, and even production finance have increasingly gravitated toward the streaming ecosystem, which often offers more lucrative contracts and global visibility. The shift of key talent and financial resources has left a void in the traditional film sector, further impacting the quality and quantity of theatrical releases.

This convergence of factors has led to a perfect storm for the South Korean film industry. While streaming has undeniably opened new avenues for South Korean content, the resulting shift in focus, combined with financial strains and audience reluctance to return to theaters, has left the industry struggling to maintain its former dominance. Though Korean cinema is still producing notable films, it faces an uphill battle to reclaim its place at the forefront of global cinema. The road ahead may require significant restructuring and adaptation to both market demands and the changing landscape of film production and consumption.

The reality of South Korean cinema’s struggles is likely a combination of the three major factors: the long-lasting impact of COVID-19, rising cinema ticket prices, and the growing dominance of streaming platforms. These challenges have exacerbated pre-existing structural issues within the industry, such as escalating production budgets and underdeveloped ancillary markets, making it harder for Korean filmmakers and producers to navigate the evolving landscape.

Even before the pandemic, South Korean cinema had been facing rising production costs, with many films being made on larger budgets in hopes of reaching international markets. However, with the pandemic bringing both financial strain and reduced audience engagement, these inflated production costs became even more problematic. Coupled with the relatively underdeveloped secondary markets (such as merchandise, television distribution, and streaming), these structural issues put additional pressure on the industry to remain profitable.

In response to these challenges, Korean producers and distributors initially turned to streaming platforms as a lifeline. Early on during the pandemic, several films were sold directly to platforms like Netflix and local streaming services, providing an alternative revenue stream when cinemas were forced to close. This move helped the industry maintain some cash flow but also marked a significant shift in the business model, with more content going digital-first.

However, after the initial surge of interest in streaming, many in the industry hoped that the traditional theatrical market would rebound once COVID-related restrictions, such as social distancing, were lifted. Producers and distributors held on to completed films, waiting for the moment when audiences would flock back to theaters, as they had before the pandemic. Unfortunately, this recovery has been slower than anticipated. With continued high ticket prices, a shift in audience behavior, and the competition from increasingly sophisticated streaming platforms, the hoped-for resurgence of the box office has yet to materialize on the scale the industry had hoped for.

As a result, the South Korean film industry is facing a precarious balancing act. The transition to streaming has provided short-term relief, but it has also brought about a rethinking of traditional distribution models. Meanwhile, the struggle to address long-standing structural issues—like the rising costs of production and the lack of robust ancillary markets—means that South Korean cinema must evolve quickly to adapt to the new realities of both global film consumption and the demands of a post-pandemic world.

Until 2019, South Korea had firmly established itself as a global cinema powerhouse, consistently punching above its weight in the film industry. It was the world’s fourth-largest theatrical market, driven by an exceptionally high per-capita cinema attendance rate. South Koreans were avid moviegoers, regularly flocking to theaters to enjoy both local and international films. This strong cinema culture supported a vibrant local film industry, which regularly captured around 50% of the total box office sales in its home market.

The success of the South Korean film industry was built on a combination of factors: a rich history of innovative filmmaking, compelling narratives, and a high level of domestic production that resonated deeply with local audiences. Filmmakers were able to create content that not only catered to domestic tastes but also garnered attention on the international stage, with films like Parasite and Oldboy achieving global recognition.

This cultural landscape allowed Korean cinema to thrive both in the local market and internationally, setting the stage for unprecedented success. However, this momentum came to a halt in 2020 with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which drastically altered the dynamics of the global film industry. The once-booming theater industry in South Korea, like in many other countries, saw a sharp decline in attendance due to health measures, lockdowns, and public fears surrounding large gatherings.

Despite initial hopes that the market would quickly recover, the reality has been more complex. The shift in audience behavior—accelerated by the rise of streaming platforms—has had a lasting effect. While South Korea had been known for its ability to maintain a dominant share of the box office, the pandemic revealed vulnerabilities in the industry’s reliance on theatrical sales alone, especially in an era where digital consumption is becoming the norm. The South Korean film industry now faces the challenge of rebuilding its theatrical audience while navigating the increasingly competitive landscape of streaming and digital media.

In short, the rapid growth and prominence that South Korean cinema enjoyed until 2019 has been stunted by the pandemic, and the industry is now working to regain its place in a very different market environment.

In 2022 and 2023, the film landscape began to shift as Hollywood rapidly ramped up its releases, nearly returning to pre-COVID levels. Major studios, eager to recapture audiences and recover lost revenue, opened their pipelines and pushed out blockbuster after blockbuster, re-establishing Hollywood’s dominance at the global box office. In contrast, South Korean rights holders adopted a more cautious approach. Rather than rushing to release films, many chose to space out their releases, announcing dates only to delay them as they sought what they considered optimal opportunities for success.

This more conservative approach was driven by a mix of factors, including the uncertain state of the post-pandemic film market, fluctuating audience behavior, and the desire to avoid overcrowding the market. However, this strategy inadvertently allowed Hollywood to fill the void left by South Korean cinema, further cementing its global dominance. As Hollywood films filled the theaters, the public perception of Korean films began to shift. With releases spaced out and delays becoming common, many audiences began to view Korean films as old or outdated, fueling a sense that they were out of touch with the current cinematic trends.

This shift in perception had significant consequences. Cinema operators, facing lower attendance and struggling to compete with the flood of Hollywood content, began to close theaters. With fewer local releases to fill screens and diminished box office returns, the once-thriving theater ecosystem in South Korea, which had been a hallmark of the industry, was now under serious threat.

The gap created by delayed Korean releases, coupled with the strong and steady flow of Hollywood content, highlighted a growing divide. Korean cinema, once a dominating force both domestically and internationally, now faced an uphill battle to regain its former relevance. With audiences increasingly turning to streaming platforms and Hollywood films occupying theater screens, South Korean filmmakers and distributors are under increasing pressure to adapt quickly—whether by embracing new distribution models or finding ways to reinvigorate the local theatrical experience.

South Korea’s box office performance in 2022 and 2023 painted a sobering picture of the industry’s post-pandemic recovery. In 2022, the box office grossed KRW 1.16 billion (approximately $884 million at January 2024 exchange rates). While there was a modest 9% growth in 2023, reaching KRW 1.261 billion (about $964 million), this still represented a significant shortfall compared to the pre-pandemic peak of $1.46 billion in 2019. The 2023 figures were roughly 44% behind the high point achieved before the pandemic, signaling the ongoing struggles of the industry.

For Korean producers, the situation was even more concerning. Their share of the domestic market fell to 48%, marking a notable decline. While this still represented a reasonable end-of-year figure, it underscored a larger trend of diminished local content dominance. The lackluster box office returns, combined with the increasing influence of Hollywood and other international films, left Korean cinema facing a serious challenge to maintain its previous market strength.

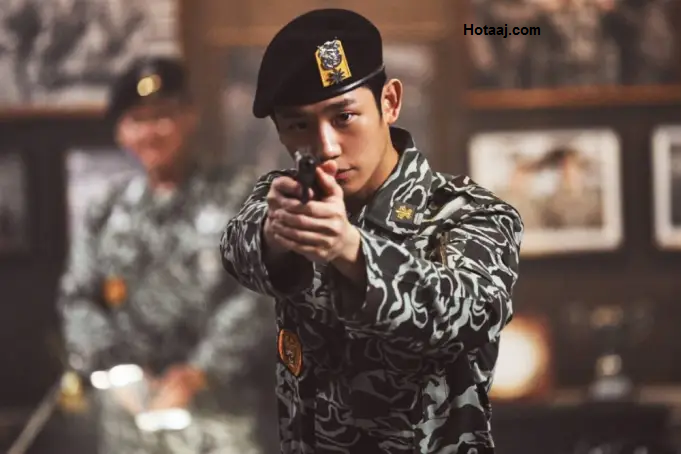

Despite these struggles, the industry managed to salvage some of its prestige with an unexpected hit toward the end of 2023. 12:12: The Day, a film that became a surprise box office success in November and December, provided a much-needed boost. The film’s strong performance offered a glimmer of hope, helping to bolster local market share and reminding audiences of the potential of Korean cinema when it hits the right note with viewers.

However, this success was not enough to fully reverse the industry’s overall decline. The numbers clearly reflect the ongoing challenges of the South Korean film market, which is grappling with reduced audience attendance, competition from international films, and the growing dominance of streaming platforms. For Korean producers, finding a way to recapture market share and revive the cinematic experience in theaters will remain a top priority in the years ahead.

Korea’s theatrical market has clearly become more uneven in recent years. Whereas the country had once enjoyed a steady stream of several hundred film releases annually, providing a relatively balanced landscape for both big-budget blockbusters and smaller films, the market has increasingly become polarized and hit-driven. This shift has created an environment where only a handful of films make significant box office impacts, while many others struggle to gain traction.

In 2023, there were some notable positive surprises amidst this uneven landscape. One of the biggest successes was The Roundup: No Way Out, the third installment in the Don Lee-led comedy-action franchise. This film exceeded expectations, grossing an impressive $75.5 million, far surpassing initial projections. Its success was a testament to the staying power of well-loved franchises in Korea, particularly those with established stars like Don Lee, whose charm and action-packed appeal resonated strongly with audiences.

Another standout was Concrete Utopia, a brainy post-apocalyptic action drama that earned a respectable $27 million at the box office. While not a massive hit by global standards, the film’s performance was noteworthy, especially considering it was also selected as Korea’s official submission for the International Feature Film category at the Oscars. This nomination helped bolster its reputation on the global stage and added a sense of prestige to its commercial success.

However, not all films had the same level of success. Smugglers, a female-led crime drama directed by Ryoo Seung-wan, earned a solid $35.8 million, but it did not reach the high-grossing numbers of Ryoo’s earlier works, such as Veteran. While Smugglers was a competent and well-received film, its performance indicated that even established directors with strong track records may not be immune to the shifting dynamics of the Korean film market, where audience tastes have become more selective and films must compete not only with each other but also with streaming services and international content.

These examples highlight the growing divide in Korea’s film industry: while there are still successes, the market is increasingly defined by blockbusters and surprise hits, with many films struggling to find an audience. This trend is a reflection of a broader global shift in the entertainment landscape, where the dominance of streaming platforms and changing audience behaviors have made it more difficult for mid-tier films to thrive in the traditional theatrical model. The future of Korean cinema may depend on its ability to adapt to this new environment, finding innovative ways to engage viewers both in theaters and on digital platforms.

The political thriller 12.12: The Day, a fictionalized reconstruction of South Korea’s 1979 military coup, emerged as a significant success in a struggling film market. Despite delving into a difficult and tumultuous period of Korean history, the film garnered both critical acclaim and public interest. It ran in theaters for months, ultimately earning $83.1 million at the box office. Its success highlighted the potential for well-executed, historically poignant films to thrive even amid the market’s downturn.

However, 2023’s early months saw a mix of results for Korean films. Exhuma and The Roundup: Punishment, which premiered at the Berlin Film Festival, not only performed strongly but also helped propel March to a record box office, demonstrating the enduring appeal of genre films. At the same time, the market continued to reflect a stark contrast between success and failure. Films like The Moon, a high-budget space epic, and Ransomed, a kidnapping drama, underperformed at the box office, grossing only $3.75 million and $7.35 million respectively. The release of Road to Boston, delayed until the Chuseok holiday, also saw disappointing returns with just $6.82 million.

These struggles point to a significant financial downturn for the Korean film industry, which was evident at Berlin’s European Film Market. Korean sales companies presented smaller slates of films, budgets were lower, and some distributors even skipped the event in favor of other markets like FilMart or MIPCOM.

Despite these challenges, there is cautious optimism about the industry’s recovery. Exhuma and Punishment have provided some momentum, but the long-term outlook remains uncertain. Industry professionals like Kim Won-kuk, head of Hive Media and producer of 12.12: The Day, suggest that the recovery is still fragile. “After the pandemic, the Korean market suffered from a crisis. Now it is recovering. But investors and distributors have spent their capital on other content. That makes it difficult if you are trying to make a new film,” Kim says.

Kim advocates for more government intervention to protect cinema from the growing influence of streaming platforms like Netflix. He argues that if audiences believe they can watch films at home shortly after their theatrical release, it could further harm cinema attendance. To address this, the government has introduced a new policy requiring films that receive state funding to commit to a four-month theatrical window before streaming, though exceptions may apply for smaller films with budgets under KRW3 billion ($2.25 million).

This move has divided the industry. Producers, distributors, and exhibitors generally support the policy, believing it could help sustain theater attendance and protect the local film industry. However, streamers oppose the restriction, arguing that it limits viewer choice and reduces the incentive to invest in theatrical films. Companies like CJ Group, which operates both a cinema chain and the Tving streaming platform, find themselves caught between these competing interests.

In addition to the policy on release windows, the South Korean government announced in April that it would abolish a 3% tax on cinema tickets, a measure intended to ease inflationary pressure on consumers. However, this tax revenue had previously supported independent and artistic film projects through the Korean Film Council’s cinema development fund, raising concerns about the long-term impact on smaller productions.

Despite these setbacks, some in the industry remain determined to move forward. Kim Won-kuk is preparing Harbin, a big-budget war action film set in China, which he hopes will become a tentpole hit for the summer or fall. Kim Young-min, the producer of Exhuma, also remains confident, stating, “If you believe in what you are making, audiences will see, understand and acknowledge your confidence.”

As the Korean film industry continues to navigate these turbulent times, it remains clear that a mix of bold storytelling, strategic production, and government support may be key to its recovery. The challenges are significant, but the industry’s resilience and ability to adapt will likely determine its future.

Courtesy: Arirang News

References

[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure – Capacity”. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ “Table 6: Share of Top 3 distributors (Excel)”. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ “Table 1: Feature Film Production – Method of Shooting”. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Table 11: Exhibition – Admissions & Gross Box Office (GBO)”. UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Stamatovich, Clinton (25 October 2014). “A Brief History of Korean Cinema, Part One: South Korea by Era”. Haps Magazine. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Paquet, Darcy (2012). New Korean Cinema: Breaking the Waves. Columbia University Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0231850124..

- ^ Jump up to:a b Min, p.46.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Chee, Alexander (16 October 2017). “Park Chan-wook, the Man Who Put Korean Cinema on the Map”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Nayman, Adam (27 June 2017). “Bong Joon-ho Could Be the New Steven Spielberg”. The Ringer. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Jin, Min-ji (13 February 2018). “Third ‘Detective K’ movie tops the local box office”. Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ 오, 승훈; 김, 경애 (2 November 2021). “한국 최초의 영화관 ‘애관극장’ 사라지면 안되잖아요” [“We Can’t Let the First Movie Theater in Korea, ‘Ae Kwan Theater’ Disappear”]. The Hankyoreh (in Korean). Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ 이, 재덕 (7 February 2015). 저당 잡힌 ‘109살 한국 예술의 요람’ 단성사는 웁니다 [Dansungsa, the ‘109 Year Old Cradle of Korean Cinema’, Weeps After Being Mortgaged]. Kyunghyang Shinmun. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ “Viva Freedom! (Jayumanse) (1946)”. Korean Film Archive. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Gwon, Yeong-taek (10 August 2013). 한국전쟁 중 제작된 영화의 실체를 마주하다 [Facing the reality of film produced during the Korean War]. Korean Film Archive (in Korean). Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Paquet, Darcy (1 March 2007). “A Short History of Korean Film”. KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Paquet, Darcy. “1945 to 1959”. KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ McHugh, Kathleen; Abelmann, Nancy, eds. (2005). South Korean Golden Age Melodrama: Gender, Genre, and National Cinema. Wayne State University Press. pp. 25–38. ISBN 0814332536.

- ^ Goldstein, Rich (30 December 2014). “Propaganda, Protest, and Poisonous Vipers: The Cinema War in Korea”. The Daily Beast. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Paquet, Darcy. “1960s”. KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Prizes & Honours 1961”. Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Rousse-Marquet, Jennifer (10 July 2013). “The Unique Story of the South Korean Film Industry”. French National Audiovisual Institute (INA). Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kim, Molly Hyo (2016). “Film Censorship Policy During Park Chung Hee’s Military Regime (1960-1979) and Hostess Films” (PDF). IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies. 1 (2): 33–46. doi:10.22492/ijcs.1.2.03 – via wp-content.

- ^ Gateward, Frances (2012). “Korean Cinema after Liberation: Production, Industry, and Regulatory Trend”. Seoul Searching: Culture and Identity in Contemporary Korean Cinema. SUNY Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0791479339.

- ^ Kai Hong, “Korea (South)”, International Film Guide 1981, p.214. quoted in Armes, Roy (1987). “East and Southeast Asia”. Third World Film Making and the West. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-520-05690-6.

- ^ Taylor-Jones, Kate (2013). Rising Sun, Divided Land: Japanese and South Korean Filmmakers. Columbia University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0231165853.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Paquet, Darcy. “1970s”. KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Min, p.51-52.

- ^ Hartzell, Adam (March 2005). “A Review of Im Kwon-Taek: The Making of a Korean National Cinema”. KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Chua, Beng Huat; Iwabuchi, Koichi, eds. (2008). East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 16–22. ISBN 978-9622098923.

- ^ Jameson, Sam (19 June 1989). “U.S. Films Troubled by New Sabotage in South Korea Theater”. Los Angeles Times.

- ^ “‘Movie Industry Heading for Crisis'”. The Korea Times.

- ^ Brown, James (9 February 2007). “Screen quotas raise tricky issues”. Variety.

- ^ “Korean movie workers stage mass rally to protest quota cut”. Korea Is One. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ Artz, Lee; Kamalipour, Yahya R., eds. (2007). The Media Globe: Trends in International Mass Media. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 978-0742540934.

- ^ Rosenberg, Scott (1 December 2004). “Thinking Outside the Box”. Film Journal International. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Lee, Hyo-won (18 November 2013). “Original ‘Oldboy’ Gets Remastered, Rescreened for 10th Anniversary in South Korea”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Box Office: All Time”. Korean Film Council. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Pomerantz, Dorothy (8 September 2014). “What The Economics Of ‘Snowpiercer’ Say About The Future Of Film”. Forbes. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Kang Kim, Hye Won (11 January 2018). “Could K-Film Ever Be As Popular As K-Pop In Asia?”. Forbes. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ “PARASITE Crowned Best Foreign Language Film at Golden Globes”. Korean Film Biz Zone.

- ^ Khatchatourian, Klaritza Rico,Maane; Rico, Klaritza; Khatchatourian, Maane (10 February 2020). “‘Parasite’ Becomes First South Korean Movie to Win Best International Film Oscar”.

- ^ Leanne Dawson (2015) Queer European Cinema: queering cinematic time and space, Studies in European Cinema, 12:3, 185-204, doi:10.1080/17411548.2015.1115696.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Kim, Ungsan (2 January 2017). “Queer Korean cinema, national others, and making of queer space in Stateless Things (2011)”. Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. 9 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1080/17564905.2017.1296803. ISSN 1756-4905. S2CID 152116199.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i 김필호; C. COLIN SINGER (June 2011). “Three Periods of Korean Queer Cinema: Invisible, Camouflage, and Blockbuster”. Acta Koreana. 14 (1): 117–136. doi:10.18399/acta.2011.14.1.005. ISSN 1520-7412.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Lee, Jooran (28 November 2000). “Remembered Branches: Towards a Future of Korean Homosexual Film”. Journal of Homosexuality. 39 (3–4): 273–281. doi:10.1300/J082v39n03_12. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 11133136. S2CID 26513122.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Shin, Jeeyoung (2013). “Male Homosexuality in The King and the Clown: Hybrid Construction and Contested Meanings”. Journal of Korean Studies. 18 (1): 89–114. doi:10.1353/jks.2013.0006. ISSN 2158-1665. S2CID 143374035.

- ^ Giammarco, Tom. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 170-171) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ Balmain, Colette. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 175-176) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ Kim, Ungsan (2 January 2017). “Queer Korean cinema, national others, and making of queer space in Stateless Things (2011)”. Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. 9 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1080/17564905.2017.1296803. ISSN 1756-4905. S2CID 152116199.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Conran, Pierce. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 178-179) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Giammarco, Tom. (2013). Queer Cinema. In C. Balmain (Ed.), Directory of World Cinema: South Korea (pp. 173-174) Chicago, IL: Intellect.

- ^ 영화 ‘아가씨’ 원작… 800쪽이 금세 읽힌다. The Chosun Ilbo (in Korean). 20 July 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Shin, Chi-Yun (2 January 2019). “In another time and place: The Handmaiden as an adaptation”. Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. 11 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/17564905.2018.1520781. ISSN 1756-4905.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Peirse, Alison; Martin, Daniel (14 March 2013). Korean Horror Cinema. p. 1. doi:10.1515/9780748677658. ISBN 978-0-7486-7765-8.

- ^ The Playlist Staff (26 June 2014). “Primer: 10 Essential Films Of The Korean New Wave”. IndieWire. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ Paquet, Darcy. “Film Awards Ceremonies in Korea”. KoreanFilm.org. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ Steger, Isabella (10 October 2017). “South Korea’s Busan film festival is emerging from under a dark political cloud”. Quartz. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ “IMDb OSCARS”. IMDb. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ “Prizes & Honours”. Berlin International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ “Cannes Film Festival”. IMDb. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ “History of Biennale Cinema”. La Biennale di Venezia. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ “Announcing the TIFF ’19 Award Winners”. TIFF. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ “2013 Sundance Film Festival Announces Feature Film Awards”. Sundance Institute. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ “Telluride Film Festival”. IMDb. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ “Tokyo International Film Festival”. IMDb. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ “Locarno International Film Festival”. IMDb. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Bowyer, Justin (2004). The Cinema of Japan and Korea. London: Wallflower Press. ISBN 1-904764-11-8.

- Min, Eungjun; Joo Jinsook; Kwak HanJu (2003). Korean Film : History, Resistance, and Democratic Imagination. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-95811-6.

- New Korean Cinema (2005), ed. by Chi-Yun Shin and Julian Stringer. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0814740309