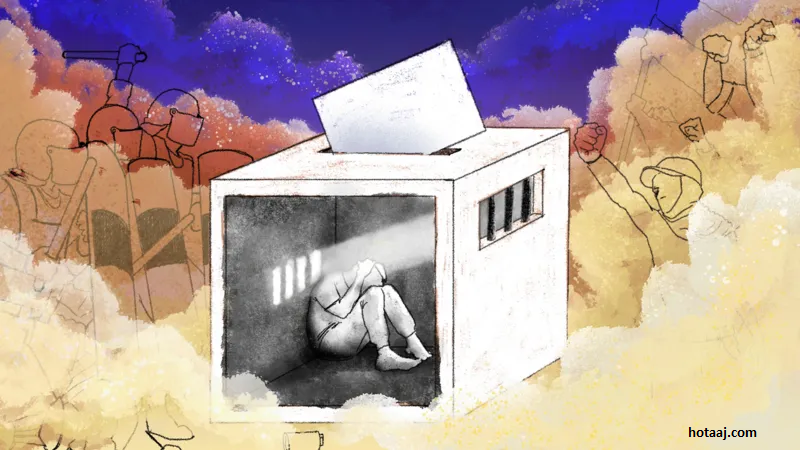

Juan, a young Venezuelan man in his 20s, was subjected to horrific physical and psychological torture after being detained in connection with protests against the controversial presidential election results of July 28. In an exclusive interview with the BBC, he bravely shared his painful experience, vowing that despite the brutal treatment he endured, he would never be silenced. “They have already tortured me and repressed me, but they will not silence me. My voice is the only thing I have left,” he declared.

Juan’s arrest occurred in the aftermath of widespread protests that erupted after the National Electoral Council (CNE), controlled by loyalists of President Nicolás Maduro, declared him the winner of the election. The opposition, led by candidate Edmundo González, accused the government of fraud, claiming the official tally did not reflect the true will of the Venezuelan people. The voting figures obtained by the opposition, supported by independent election observers, suggested a decisive victory for González.

During his detention, Juan was subjected to intense mistreatment, a fate he shares with many other detainees arrested during the protests. He claims that prisoners were given “rotten food” and were routinely subjected to brutal treatment. The most defiant individuals, he said, were confined to “torture chambers,” where they were subjected to physical and mental abuse. In some cases, detainees were left in isolation for prolonged periods, enduring severe psychological strain.

Juan was eventually released in mid-November, just days after President Maduro publicly called for judicial authorities to “rectify” any injustices in the aftermath of the mass arrests. However, his release did little to alleviate the scars left by the harrowing ordeal he had endured. Despite the suffering, Juan remains defiant in his commitment to speak out against the regime’s actions, offering a voice to those who are too afraid to speak up.

The evidence Juan shared, including documents and testimonies, corroborates his account and aligns with reports from human rights organizations and other detainees. These organizations have long decried the Venezuelan government’s crackdown on dissent, citing reports of arbitrary arrests, torture, and the silencing of opposition voices as routine practices within the country’s prisons.

Juan’s story is a stark reminder of the ongoing human rights abuses in Venezuela, where political repression, silencing of dissent, and the abuse of those who dare to oppose the government remain rampant. As Venezuela’s political crisis continues, Juan’s resolve to speak out is a testament to the resilience of those who continue to fight for justice, even in the face of unimaginable suffering.

Juan’s testimony highlights the intense climate of fear and repression that has taken hold in Venezuela, where dissent is often met with violent retaliation. The young man’s experience is not unique; many other individuals have been detained, tortured, and silenced in a bid to suppress opposition to the government’s actions. The detention and abuse of protesters following the July 28 election results underscore the lengths to which the Venezuelan authorities are willing to go to maintain their grip on power.

During his time in detention, Juan recalls being forced into cramped, unsanitary conditions where torture became an everyday reality. He described being denied access to basic human necessities, including food and clean water, while being subjected to relentless physical abuse. “They hit me in the ribs, the stomach, and they left me bruised,” he recounted. His captors also employed psychological tactics to break him down, including threats to his life and family, leaving deep scars on his mental and emotional health. Yet, despite the immense suffering, Juan maintained that he would not be cowed into silence.

He also recalled the disturbing sight of fellow detainees, many of whom were subjected to similar forms of abuse. According to Juan, those who attempted to resist were often isolated in torture chambers, a disturbing claim corroborated by various human rights organizations monitoring the situation in Venezuela. Many detainees, including those who were arrested without charges or a legal process, were subjected to long periods of detention without being given the opportunity to defend themselves or contest the allegations against them.

Juan’s case also sheds light on the broader pattern of abuse faced by political opponents, activists, and even ordinary citizens who dared to protest against the government. International human rights groups, such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have long condemned the Venezuelan government for its brutal crackdown on dissent and its attempts to stifle any form of opposition. The abuse of political prisoners has become a common tool of the government to maintain control and prevent any challenges to the authority of President Nicolás Maduro.

In addition to physical torture, Juan’s story points to the psychological toll of imprisonment in Venezuela. Detainees, many of whom are young activists like Juan, are often subjected to arbitrary arrest, solitary confinement, and in some cases, the complete absence of information regarding their fate. The uncertainty surrounding their detention adds to the stress and anxiety that political prisoners endure, making the trauma of being detained even more intense.

Despite the horrors he faced, Juan’s resilience remains unwavering. His decision to speak out is not only an act of personal defiance, but a call to the international community to hold the Venezuelan government accountable for its actions. He emphasized the importance of sharing his story, noting that many others remain behind bars, their voices silenced by fear and intimidation. By speaking out, Juan hopes to inspire others to stand up against the regime and demand justice.

Human rights organizations, both within Venezuela and internationally, continue to document cases of abuse and call for the immediate release of all political prisoners. They argue that Venezuela’s actions not only violate international human rights standards, but also violate the basic principles of justice and fairness. Juan’s case is a microcosm of the broader struggle for freedom of speech and human rights in Venezuela, where dissent is met with violence and retribution.

As the crisis in Venezuela deepens, the stories of individuals like Juan offer a glimmer of hope that change is possible. While the struggle for justice in Venezuela is far from over, Juan’s bravery in speaking out against the brutality he endured serves as a reminder of the power of individual voices in the fight for freedom. His message is clear: despite the attempts to break him, he will continue to resist and speak out against the injustices faced by the Venezuelan people.

Juan’s ordeal began in the immediate aftermath of the controversial election results. As the government declared Maduro the winner, the mood across Venezuela quickly shifted from anticipation and hope to widespread disbelief and outrage. Protesters flooded the streets to voice their discontent with what they believed to be a rigged election, but their calls for justice were met with violent repression.

Juan, who had not been actively participating in the protests, found himself caught up in the chaos. He was arrested simply for being near one of the demonstrations, a common tactic used by Venezuelan security forces to round up suspected opponents of the government. As he was taken into custody, he quickly realized that being in the wrong place at the wrong time could lead to severe consequences in a politically charged environment.

The arrest, according to Juan, was a part of a larger pattern of indiscriminate detentions carried out by authorities in the wake of the protests. Foro Penal’s Gonzalo Himiob confirmed that many individuals, including those who had not actively engaged in demonstrations, were detained for trivial reasons, such as expressing support for the opposition’s candidate, Edmundo González, or simply voicing their dissatisfaction with the electoral process on social media.

Juan, however, was not one to remain silent. During his time in detention, he spoke out against the injustice of his situation, but his defiance only earned him further punishment. His imprisonment became a vivid example of how the Venezuelan government used arrests to stifle dissent, whether it was by silencing protesters or suppressing free speech.

He described the conditions of his detention as brutal, noting that detainees, especially those accused of being opposition supporters, were treated with particular cruelty. Many of the prisoners, he said, were subjected to physical abuse and forced to endure long periods of confinement without basic necessities. The authorities, he claimed, would often refuse to provide adequate food, water, or medical attention to detainees, worsening their suffering.

But Juan’s story is not unique. It mirrors the experiences of many others who were detained in the aftermath of the election, with human rights groups reporting a surge in arbitrary arrests and unlawful detentions. For many of these detainees, their only crime was their opposition to the government’s hold on power. They were arrested for peacefully protesting or for expressing their frustration over what they saw as an election marred by fraud.

In the months since the election, both national and international voices have condemned the Venezuelan government’s handling of the protests and the widespread repression that followed. Human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have called for the immediate release of all political prisoners and for an end to the systematic abuse of detainees.

Juan’s case underscores the extreme lengths to which the Venezuelan government has gone to maintain control over the country. His experience serves as a chilling reminder of the dangers faced by those who dare to speak out against the regime and the lengths the government will go to silence opposition.

Despite his suffering, Juan remains defiant, vowing to continue speaking out against the injustices he endured. He hopes that by sharing his story, he can raise awareness of the ongoing repression in Venezuela and inspire others to stand up for their rights. His courage in the face of adversity is a testament to the resilience of Venezuela’s opposition and its determination to fight for a better future, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

Juan’s experience highlights not only the physical and psychological toll of political imprisonment but also the broader climate of fear and repression that continues to affect countless Venezuelans. As he recounted his ordeal, he emphasized how the Venezuelan authorities have perfected the art of silencing dissent through a combination of fear, intimidation, and violence. What began as a political crackdown soon turned into widespread human rights violations that continue to this day.

Upon his arrest, Juan was taken to a detention facility where he said the conditions were nothing short of inhumane. The prison, he recalled, was overcrowded, filthy, and lacked basic necessities such as clean water and medical care. Detainees, including those who had been arrested without cause, were subjected to degrading treatment, forced to sleep on the floor, and often given only rotten food to eat. But it wasn’t just the physical conditions that broke Juan’s spirit. What struck him the hardest was the psychological torment he faced. The constant threats, the isolation, and the uncertainty about his fate were the most devastating aspects of his imprisonment.

While detained, Juan was subjected to intense interrogations, during which he was threatened with worse treatment if he refused to cooperate. The authorities were particularly focused on extracting confessions and forcing detainees to implicate others in the protests or opposition activities. For Juan, this pressure was unbearable, as he was not involved in any illegal activities. He recalled the physical abuse, including being beaten by his captors, and the psychological abuse, which aimed to break his resolve. “They tried to break me mentally,” he said, recounting how they used every tactic available to silence him. Yet, through it all, he found the strength to resist. He clung to his conviction that the truth would eventually come to light, and he knew he could not allow the government to intimidate him into submission.

Juan’s release in November came after significant international pressure and the public calls for justice, especially following Maduro’s statements urging judicial authorities to review the arrests. While his release was a glimmer of hope, it didn’t bring an end to his pain. The scars, both physical and emotional, remained. He continues to grapple with the trauma of his experience and the ongoing threat of re-arrest. The Venezuelan government’s arbitrary detention of political opponents, activists, and even bystanders has become a tool of political control.

Yet, even in the face of ongoing fear and uncertainty, Juan remains steadfast in his commitment to speak out. He said that his story, though painful, is not just about his own suffering but a reflection of the broader crisis in Venezuela. “If my voice can help others, if it can shed light on the horrors we endure here, then I will not remain silent,” he said.

His resilience in the face of such adversity is a powerful reminder of the courage and determination of Venezuelans who continue to resist the government’s authoritarian rule. It also underscores the need for international solidarity and support for those who are still being persecuted for their beliefs.

Juan’s testimony is also a stark reminder to the world that Venezuela’s crisis is far from over. The repression that followed the July elections, with its waves of arbitrary arrests and violent crackdowns, is just one chapter in a long history of human rights abuses by the Venezuelan government. Human rights organizations continue to call for accountability and the immediate release of all political prisoners.

The international community, too, has a crucial role to play in holding Venezuela’s leadership accountable for its ongoing violations of human rights. Whether through diplomatic pressure, sanctions, or other means, the international community must act decisively to ensure that the voices of Venezuela’s people are not silenced.

For Juan and countless others like him, the struggle for justice continues. Their resilience in the face of repression gives hope that, despite the government’s efforts to quash dissent, the fight for freedom and democracy in Venezuela will not be extinguished. They may have endured unimaginable suffering, but their courage and their voices are far from silenced.

‘It felt like a concentration camp’

Juan’s account of his time in Tocorón prison paints a harrowing picture of the brutal conditions endured by political prisoners in Venezuela. His description of the daily suffering faced by him and his fellow inmates is a stark reminder of the severe repression that continues to characterize Venezuela’s political landscape.

Upon arriving at Tocorón, a notorious high-security prison known for its harsh treatment of inmates, Juan was subjected to both physical and psychological abuse. The guards’ cruelty began immediately, with Juan and the other detainees being stripped, beaten, and humiliated. The demands on the prisoners were degrading; they were forced to keep their heads down at all times, forbidden from making eye contact with the guards. The fear and the degradation were constant.

Juan’s cell, a cramped and unsanitary space shared with five others, offered no reprieve. The room was barely large enough for the six men to move, and the conditions were dire. The beds, described by Juan as “concrete tombs,” provided no comfort. The single toilet and shower, a mere pipe in the corner of the cell, served as both bathroom and bathing area, and access to it was limited to just six minutes a day for six people.

The lack of basic necessities was overwhelming. Juan recalls that meals were scarce and unpredictable, often arriving hours late. The physical mistreatment continued as well; prisoners were kept awake at odd hours, forced to line up for headcounts or to have their passes and numbers checked. The lack of sleep and constant anxiety made the already grueling conditions even more unbearable.

Juan also spoke of the psychological toll that the prison regime took on him and the other inmates. The guards’ arbitrary cruelty kept everyone on edge. Conversations about politics or dissent had to be whispered, as even minor acts of defiance could lead to punishment. For Juan, who was detained for his political beliefs, this atmosphere of constant fear and silence served as a harsh reminder of the regime’s desire to break the spirits of those who dared to resist.

Yet despite the unimaginable hardships, Juan’s determination never wavered. Though he was physically tortured and psychologically tormented, he refused to give in. The prison, which felt more like a concentration camp than a place of detention, became a symbol of his resolve to continue the fight for freedom.

For Juan, and countless others who have faced similar brutality, the conditions in Venezuelan prisons are not merely about imprisonment but are used as tools of control and intimidation by the government. His story is a testament to the resilience of those who, despite being subjected to unimaginable cruelty, continue to resist and fight for a better future.

Juan’s story serves as a powerful reminder to the international community about the urgent need to address the ongoing human rights violations in Venezuela. The brutal repression of political activists and dissidents cannot be allowed to continue unchecked. His experience underscores the importance of solidarity and action in the face of such blatant abuses of power.

Juan’s tale of torture and suffering in Tocorón prison is just one of many examples of the human rights abuses that continue to plague Venezuela under the rule of Nicolás Maduro. His personal account offers a glimpse into the harsh and inhumane conditions that political prisoners, activists, and ordinary citizens endure when they challenge the government.

The widespread nature of these abuses speaks to a systematic effort by the Venezuelan government to silence dissent and intimidate the population. As Juan describes, even the smallest acts of resistance or defiance—such as expressing support for the opposition, celebrating an election result that is not the government’s declared outcome, or simply discussing political matters—are met with brutal repression. The fact that he was arrested for merely being near a protest demonstrates the regime’s eagerness to quash any form of opposition, regardless of the circumstances.

While the physical abuse inflicted on prisoners like Juan is horrifying, it is the psychological torment that may leave the deepest scars. The fear of punishment for any action deemed subversive, the constant degradation, and the forced silencing of any political discussion create an atmosphere of utter despair. Juan’s experience with forced silence in prison is a grim reflection of how the Venezuelan government not only seeks to control physical spaces but also attempts to control minds and voices, stifling the very core of political freedom and expression.

This imprisonment, designed to break both the bodies and spirits of those detained, is a tactic of terror used to suppress the rising tide of discontent among the Venezuelan population. It becomes clear that Venezuela’s prison system, especially facilities like Tocorón, serves not just as places of confinement but as tools of the state’s larger strategy of repression and fear. The authorities’ actions are not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern of government-led persecution.

The international community’s role in condemning such acts becomes increasingly vital. While many governments have issued statements of concern regarding Venezuela’s human rights violations, tangible action has been lacking. Advocating for stronger international pressure, imposing targeted sanctions, and supporting human rights organizations are crucial steps in holding the Venezuelan government accountable for its actions.

Juan’s story is not only a personal account of suffering but a symbol of the broader struggle for freedom in Venezuela. His courage in speaking out against his mistreatment highlights the power of resistance even in the face of extreme adversity. His belief that his voice is the “only thing [he] has left” reflects the tenacity of those who refuse to be silenced, even after enduring the worst kinds of torture.

As his testimony unfolds, Juan joins a growing number of voices seeking justice for the abuses committed under Maduro’s regime. His release, albeit after enduring a horrific ordeal, provides a glimmer of hope that international attention may still spark change and a greater commitment to human rights in Venezuela. However, the long road to freedom and justice for many Venezuelans remains fraught with danger and uncertainty.

For Juan, his physical freedom might have been restored, but the scars left by his torment in prison will likely remain with him for life. His struggle, however, is far from over. Like many others, he is determined to continue the fight for democracy, human rights, and a Venezuela where fear no longer dictates the lives of its citizens.

As Venezuela continues to face political, social, and economic turmoil, it is stories like Juan’s that need to be heard and acted upon. The world must stand in solidarity with the brave souls who risk everything to demand change in the face of unimaginable cruelty. Until then, the voices of the oppressed will continue to rise, louder than ever, in the struggle for justice.

‘I thought I was going to die’

Juan’s account continues to expose the horrors he faced within the walls of Tocorón prison, shedding light on the dehumanizing practices and systematic cruelty employed by the Venezuelan authorities. The conditions he describes reflect an ongoing campaign of psychological and physical torment designed to break the spirits of those detained under the regime’s scrutiny.

The food, he says, was rotten, unfit for human consumption, and provided only intermittently. For many inmates, this meant extreme hunger. The comparison to food fit only for animals further highlights the disdain and disregard the authorities have for the lives of prisoners, stripping them not only of their dignity but of their basic rights to health and well-being. The treatment of detainees in such a manner only reinforces the idea that the Venezuelan government sees those imprisoned as expendable, undeserving of humane treatment.

More disturbing is the forced humiliation and physical abuse. The practice of making prisoners “walk like frogs,” a grotesque form of punishment, is emblematic of the sadistic culture of control within the prison. Such actions are meant not only to cause pain but also to strip prisoners of their humanity, turning them into mere objects of ridicule and torture. The beatings, which many inmates endured, were likely intended to instill fear, turning the prison into a place where survival was based not on rights but on submission.

The punishment cells are among the most chilling aspects of Juan’s experience. These cells, designed to isolate and break the will of detainees, were a nightmare for those unlucky enough to be placed in them. The small, dark, and suffocating spaces had the sole aim of stripping individuals of their mental stability. Juan’s story of being in a one-meter by one-meter cell with only one meal every two days reflects the extreme deprivation and neglect suffered by those in prison. The darkness, the hunger, and the isolation combined to form an environment of hopelessness, where prisoners were forced to confront not only physical pain but also the mental anguish of knowing they were trapped with no means of escape.

Juan’s recollection of “Adolfo’s bed,” a torture chamber designed to deprive prisoners of oxygen until they fainted, takes the cruelty to even darker depths. It is a stark portrayal of the inhumane tactics employed by the authorities, using fear and physical trauma to extract compliance from the most rebellious or outspoken prisoners. This method of suffocation—denying basic air and life to a person—is not only a direct attack on the body but a symbolic representation of how the regime seeks to suppress dissent in every possible way.

The very fact that Juan survived this experience and managed to endure despite the brutality he faced speaks to the strength of his spirit and the resilience of many detainees who have suffered similar fates. His will to survive, his drive to expose the injustices he witnessed, and his hope that one day he would be freed allowed him to endure the unimaginable suffering.

Juan’s story is not an isolated one; it is part of a larger pattern of torture and abuse reported by human rights organizations in Venezuela. His testimony is a reminder of the ongoing struggle of political prisoners, human rights defenders, and activists in Venezuela, whose voices are silenced through violence, fear, and oppression. This level of cruelty, as described by Juan, cannot be tolerated or ignored. It calls for the international community to take a stand, demand accountability from the Venezuelan authorities, and continue to advocate for the release of all political prisoners who are subjected to similar horrors.

Juan’s voice, although temporarily silenced by the darkness and pain of his confinement, remains a powerful symbol of resistance against a regime that thrives on fear and repression. His words, now heard beyond the walls of Tocorón, serve as a beacon of hope for those still trapped within the system, and a call to action for the world to intervene and ensure justice is served.

Juan’s harrowing account of his time in Tocorón prison underscores the disturbing reality faced by political detainees under the Venezuelan regime. His testimony provides a stark picture of the extent to which the government has gone to silence opposition and crush any hope for democratic change within the country. In his narrative, he reveals not only the physical brutality imposed on him but also the mental and emotional toll of being subjected to such cruelty.

As Juan describes the psychological torment, it becomes clear that the abuse wasn’t just meant to break their bodies but also to dismantle their will to resist. The daily regimen of forced standing, humiliation, and intimidation served to instill a sense of hopelessness, a constant reminder that they were at the mercy of a regime that saw their lives as expendable. The arbitrary waking times, enforced group lineups, and humiliating punishments created an environment where every moment was filled with anxiety and fear. Even the small, fleeting moments of relief—such as the brief six-minute showers—were marred by the constant uncertainty that characterized their existence behind bars.

In Juan’s case, his survival was marked not only by the pain he endured but also by his unwavering determination to resist the forces that sought to silence him. His memories of the food, the cells, and the constant threat of physical violence are potent reminders of the regime’s desire to break down the spirit of every individual who dares to oppose it. The psychological effect of this kind of torture cannot be overstated. Prisoners like Juan were not just deprived of food and shelter; they were systematically dehumanized, stripped of dignity, and subjected to the whims of the guards. This form of imprisonment aims to force individuals to question their own identity, their beliefs, and their very sense of self-worth.

The fact that Juan was able to persevere is a testament to his strength and resilience, but it also highlights the harsh reality faced by thousands of other detainees in Venezuela. Many of them do not survive the abuse or the trauma, and those who do often emerge broken, physically and emotionally scarred. The story of “Adolfo’s bed” symbolizes the extreme measures taken to impose fear and maintain control. The suffocation of the prisoners—quite literally robbing them of air—reflects the metaphorical suffocation of freedom that Juan and many others experienced.

Despite the brutality, Juan’s desire for justice and the belief that the truth would eventually come to light remained unwavering. His hope that his story would be heard, that the world would take notice, and that one day he would be freed provided him with the inner strength to endure the unimaginable horrors. His testimony is a reminder that political imprisonment in Venezuela is not just an act of physical confinement but also a calculated effort to destroy the spirit of dissent, to render voices of opposition powerless through fear, suffering, and isolation.

Juan’s story is not just a personal account of suffering; it is a call to action for the international community. It underscores the need for greater awareness of the ongoing human rights abuses in Venezuela and the urgent necessity of holding those responsible accountable. His case is far from unique, and countless others are suffering in similar conditions, deprived of their rights and subjected to the same systematic abuse. The international community must not turn a blind eye to these atrocities; justice must be pursued for all political prisoners, and the Venezuelan government must be held responsible for the human rights violations committed against its people.

Juan’s ordeal at Tocorón prison is a stark reminder that the fight for democracy, human rights, and justice is ongoing in Venezuela. His survival, and his determination to speak out, serves as a symbol of hope for all those who continue to resist the oppressive regime, even at great personal cost. His story proves that even in the darkest of times, the human spirit can endure and fight back, and that the truth will eventually rise above the walls of fear and repression.

Reports of crimes against humanity

The grim reality inside Venezuelan prisons, especially the infamous Tocorón facility, reflects systemic abuse and violations of basic human rights. Juan’s description of his limited exercise opportunities, where inmates are allowed only 10 minutes of outdoor time three times a week, paints a chilling picture of the physical and psychological isolation many detainees endure. With the option to stay in their cells instead of exercising, many choose to remain confined, further exacerbating the toll on their mental and physical health.

Foro Penal’s Gonzalo Himiob, a human rights advocate, describes these conditions as “deplorable,” underscoring the extensive rights violations that prisoners face. One of the most disturbing aspects is the denial of access to legal representation. Detainees are typically assigned public defenders, leaving them with limited recourse for legal protection. According to Himiob, the government’s tight control over legal access ensures that any violations of due process are kept hidden from outside scrutiny. Allowing detainees access to private lawyers would provide a way to document and expose the abuses occurring behind the prison walls, and the government has chosen to keep this avenue closed to prevent such revelations.

This pattern of repression is not just confined to the prisons. In the months leading up to the presidential election and in the aftermath of the protests, there were widespread reports of serious human rights violations. UN experts, in their October report, highlighted a range of abuses, including political persecution, excessive use of force, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial executions carried out by state security forces and affiliated civilian groups. These reports paint a grim picture of the Venezuelan government’s treatment of its citizens, particularly those who resist its authority.

The international community has taken note of these violations, with the International Criminal Court (ICC) currently investigating the Venezuelan government for possible crimes against humanity. The investigation has the potential to hold the regime accountable for its actions, but the road to justice remains uncertain. The Venezuelan government continues to deny the accusations, dismissing the investigation as politically motivated, and framing the international attention as an attempt to exploit international criminal justice mechanisms for political gain.

The BBC’s request for an interview with the Venezuelan Public Prosecutor’s Office regarding the allegations of mistreatment and torture was met with silence, highlighting the lack of transparency and accountability within the government. This silence speaks volumes about the entrenched culture of impunity that surrounds these human rights violations. As detainees like Juan continue to suffer in silence, the international community must persist in demanding justice and accountability for the widespread abuses occurring in Venezuela’s prisons and beyond.

Juan’s testimony is just one among many, and it serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of the Venezuelan government’s crackdown on dissent. His story reflects the broader struggle for basic human rights and freedoms in Venezuela, a fight that continues despite the government’s efforts to suppress it. While the regime may seek to silence the voices of those who resist, the truth of their suffering persists, and the call for justice grows louder.

Juan’s account is just a small part of a much larger story that underscores the grim reality many Venezuelans face under the current regime. His testimony, along with the reports from organizations like Foro Penal and the United Nations, paints a picture of systematic oppression that extends far beyond the prison walls.

The emotional and psychological toll on detainees like Juan is immeasurable. Forced to endure constant abuse, isolation, and the deprivation of basic human rights, many prisoners emerge from their ordeals mentally and physically broken. The conditions in Tocorón prison, where Juan was held, are particularly harrowing. The overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and lack of adequate food and water highlight a deliberate strategy of dehumanization. When prisoners are given rotten food, restricted access to exercise, and forced into isolation or punishment cells, it is a clear indication of a government that is willing to go to extreme lengths to break the spirits of those who challenge its authority.

In many cases, the government not only targets political activists but also ordinary citizens who find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. As Gonzalo Himiob of Foro Penal points out, people are arrested for seemingly minor offenses, such as celebrating an opposition leader’s victory or posting a critical comment on social media. This kind of broad, indiscriminate repression creates an atmosphere of fear, where people are reluctant to speak out or take action, knowing the consequences they may face.

For those who remain defiant, such as Juan, the path is often one of continuous suffering. The physical and psychological torture he endured in the detention center, including solitary confinement, beatings, and the deprivation of food and sleep, is emblematic of a regime that has no qualms about using brutality to stifle opposition. The psychological scars left by such treatment may never fully heal, and for many, the trauma will linger long after their release.

The international community’s response to these violations has been slow but increasingly vocal. While the United Nations has documented the extensive abuses, including forced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, these reports have often been met with denial from the Venezuelan government. The ICC’s investigation into possible crimes against humanity represents a critical step in the pursuit of justice, but it remains to be seen whether this will lead to meaningful accountability. The Venezuelan government’s attempt to dismiss these investigations as politically motivated shows its determination to cling to power, even at the expense of human rights.

Despite the overwhelming challenges, individuals like Juan continue to resist. Their courage in the face of such extreme oppression is a testament to the strength of the human spirit. The fact that Juan has survived these ordeals and continues to speak out, despite the risks, is a powerful reminder that even in the darkest of circumstances, there are those who will not be silenced.

The international community must continue to pressure the Venezuelan government to end the widespread abuse of its people and hold those responsible accountable. Organizations like Foro Penal play a crucial role in documenting abuses, supporting victims, and calling for justice. But this fight is far from over. As long as the regime continues its repressive tactics, there will be many more like Juan whose voices need to be heard, and whose stories must be shared.

The call for justice, freedom, and human dignity in Venezuela must not be forgotten. The world must stand in solidarity with those who continue to suffer and fight for their basic rights.

‘I’m no longer afraid of the government’

Juan’s release in November did little to erase the ongoing hardships faced by many others still imprisoned under the Maduro regime. As of December 30, Foro Penal reported nearly 1,800 political prisoners in Venezuela, a stark reminder of the government’s continuing crackdown on dissent. Juan’s own experience of abuse and suffering in Tocorón prison continues to haunt him, especially as he thinks of those left behind. The hope for change is palpable among prisoners, particularly with the arrival of January 10, 2025—an important date for many Venezuelans.

That day is when Edmundo González, the exiled opposition candidate, intends to return to Venezuela and assume the presidency, claiming a victory based on election tallies gathered by the opposition and independent observers. The opposition believes these tallies reflect a clear victory for González, who is viewed by some as the rightful president. These numbers, representing 85% of the total, were publicly shared and reviewed by international election monitors who support González’s claim. However, his return remains uncertain, as Maduro’s government has issued an arrest warrant for him and controls the National Assembly, making it unclear how González will be able to claim the presidency.

In the face of this uncertainty, the political prisoners in Tocorón—many of whom share Juan’s unwavering belief in González’s victory—hold on to a fragile hope. Their thoughts are anchored on the prospect of a new government, and they dream of their eventual release. But the Maduro government is resolute in dismissing any talk of a political transition, labeling it a “conspiracy” and issuing threats against those who challenge the current order.

Juan’s sense of freedom is bittersweet, as he feels guilt for being out of prison while his comrades endure suffering. Yet, his determination to support González on January 10 is clear. His willingness to take to the streets and defy the government shows his unyielding spirit and his belief in a future where Venezuela is free from tyranny.

Juan, like many others, has already been accused of the most severe crimes—terrorism—despite his commitment to peaceful activism. He describes himself as a young man who loves his country and strives to help those around him, yet the government has portrayed him as an enemy of the state. His decision to leave a written testimony in a safe place in case anything happens to him reveals the level of danger he still faces. In spite of these risks, Juan’s resolve remains firm. He no longer fears the Venezuelan government, demonstrating the resilience of those who fight for justice, even at great personal cost.

Juan’s story is emblematic of the broader struggle in Venezuela—one marked by political persecution, repression, and an unwavering desire for change. The hopes of those still imprisoned, including the men in Tocorón, rest on the possibility of a shift in leadership. Whether that hope becomes reality remains to be seen, but the courage of individuals like Juan continues to inspire others to push for a future where their voices are heard and their rights respected. The road to change is fraught with danger, but for those like Juan, the desire for freedom is more powerful than fear.

Courtesy: USA TODAY

References

- ^ “World Development Indicators: Rural environment and land use”. World Development Indicators, The World Bank. World Bank. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “World Population Prospects 2022”. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100” (XSLX) (“Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)”). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Report for Selected Countries and Subjects”.

- ^ Dressing, David. “Latin America”. Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. v. 5, 390

- ^ Bethell, Leslie (August 1, 2010). “Brazil and ‘Latin America'”. Journal of Latin American Studies. 42 (3): 457–485. doi:10.1017/S0022216X1000088X. ISSN 1469-767X.

- ^ Gistory (September 17, 2015). “Is Brazil Part of Latin America? It’s Not an Easy Question”. Medium. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ “Latin America” definition Archived September 22, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bilbao, Francisco (June 22, 1856). “Iniciativa de la América. Idea de un Congreso Federal de las Repúblicas” (in Spanish). París. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017 – via Proyecto Filosofía en español.

- ^ Britton, John A. (2013). Cables, Crises, and the Press: The Geopolitics of the New Information System in the Americas, 1866–1903. UNM Press. pp. 16–18. ISBN 9780826353986.

- ^ Mignolo, Walter (2005). The Idea of Latin America. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 77–80. ISBN 978-1-4051-0086-1.

- ^ Ardao, Arturo (1980). Genesis de la idea y el nombre de América Latina (PDF). Caracas, Venezuela: Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos Rómulo Gallegos. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Rojas Mix, Miguel (1986). “Bilbao y el hallazgo de América latina: Unión continental, socialista y libertaria…”. Caravelle. Cahiers du monde hispanique et luso-brésilien. 46 (1): 35–47. doi:10.3406/carav.1986.2261. ISSN 0008-0152.

- ^ Gobat, Michel (December 1, 2013). “The Invention of Latin America: A Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism, Democracy, and Race”. The American Historical Review. 118 (5): 1345–1375. doi:10.1093/ahr/118.5.1345. ISSN 0002-8762. S2CID 163918139.

- ^ Edward, Shawcross (February 6, 2018). France, Mexico and informal empire in Latin America, 1820–1867 : equilibrium in the New World. Cham, Switzerland. p. 120. ISBN 9783319704647. OCLC 1022266228.

- ^ Gutierrez, Ramon A. (2016). “What’s in a Name?”. In Gutierrez, Ramon A.; Almaguer, Tomas (eds.). The New Latino Studies Reader: A Twenty-First-Century Perspective. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-520-28484-5. OCLC 1043876740.

The word latinoamericano emerged in the years following the wars of independence in Spain’s former colonies […] By the late 1850s, californios were writing in newspapers about their membership in América latina (Latin America) and latinoamerica, calling themselves Latinos as the shortened name for their hemispheric membership in la raza latina (the Latin race). Reprinting an 1858 opinion piece by a correspondent in Havana on race relations in the Americas, El Clamor Publico of Los Angeles surmised that ‘two rival races are competing with each other … the Anglo Saxon and the Latin one [la raza latina].’

- ^ “América latina o Sudamérica?, por Luiz Alberto Moniz Bandeira, Clarín, 16 de mayo de 2005″. Clarin.com. May 16, 2005. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ José María Torres Caicedo (September 26, 1856). “Las dos Américas” (in Spanish). Venice. Archived from the original on July 22, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2013 – via Proyecto Filosofía en español.

- ^ Bilbao, Francisco. “Emancipación del espíritu de América”. Francisco Bilbao Barquín, 1823–1865, Chile. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ RAE (2005). Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas. Madrid: Santillana Educación. ISBN 8429406239. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ Rangel, Carlos (1977). The Latin Americans: Their Love-Hate Relationship with the United States. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-15-148795-0. Skidmore, Thomas E.; Peter H. Smith (2005). Modern Latin America (6th ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0-19-517013-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Torres, George (2013). Encyclopedia of Latin American Popular Music. ABC-CLIO. p. xvii. ISBN 9780313087943.

- ^ Butland, Gilbert J. (1960). Latin America: A Regional Geography. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 115–188. ISBN 978-0-470-12658-5.

Dozer, Donald Marquand (1962). Latin America: An Interpretive History. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1–15. ISBN 0-87918-049-8.

Szulc, Tad (1965). Latin America. New York Times Company. pp. 13–17. ISBN 0-689-10266-6.

Olien, Michael D. (1973). Latin Americans: Contemporary Peoples and Their Cultural Traditions. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-03-086251-9.

Black, Jan Knippers, ed. (1984). Latin America: Its Problems and Its Promise: A Multidisciplinary Introduction. Boulder: Westview Press. pp. 362–378. ISBN 978-0-86531-213-5.

Burns, E. Bradford (1986). Latin America: A Concise Interpretive History (4th ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall. pp. 224–227. ISBN 978-0-13-524356-5.

Skidmore, Thomas E.; Peter H. Smith (2005). Modern Latin America (6th ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 351–355. ISBN 978-0-19-517013-9. - ^ Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings Archived April 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, UN Statistics Division. Accessed on line May 23, 2009. (French Archived December 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Latin America and the Caribbean Archived May 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The World Bank. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ “Country Directory. Latin American Network Information Center-University of Texas at Austin”. Lanic.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo, Latin America: The Allure and Power of an Idea. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2017, 1, 3.

- ^ Francisco Bilbao, La América en peligro, Buenos Aires: Impr. de Berheim y Boeno 1862, 14, 23, quoted in Tenorio-Trillo, Latin America, p. 5.

- ^ Gongóra, Alvaro; de la Taille, Alexandrine; Vial, Gonzalo. Jaime Eyzaguirre en su tiempo (in Spanish). Zig-Zag. p. 223.

- ^ “South America, Latin America”. Reflexions. University of Liège. Archived from the original on November 24, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ “Language and education in Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao”. ResearchGate. Archived from the original on September 25, 2024. Retrieved December 16, 2024.

- ^ María Alejandra Acosta Garcia; González, Sheridan; Ma. de Lourdes Romero; Reza, Luis; Salinas, Araceli (June 2011). “Three”. Geografía, Quinto Grado [Geography, Fifth Grade] (Second ed.). Mexico City: Secretaría de Educación Pública [Secretariat of Public Education]. pp. 75–83 – via Comisión Nacional de Libros de Texto Gratuitos (CONALITEG).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Central Intelligence Agency (2023). “The World Factbook – Country Comparisons: Population”. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “United Nations Statistics Division – Demographic and Social Statistics”. unstats.un.org. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Téléchargement du fichier d’ensemble des populations légales en 2017 Archived October 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, INSEE

- ^ Ospina, Jose (October 28, 2018). “Is there a right-wing surge in South America?”. DW. Archived from the original on December 31, 2022. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ “Conservative Lacalle Pou wins Uruguay presidential election, ending 15 years of leftist rule”. France 24. November 29, 2019. Archived from the original on June 13, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ Jordi Zamora. “China’s double-edged trade with Latin America”. September 3, 2011. AFP.

- ^ Casey, Nicholas; Zarate, Andrea (February 13, 2017). “Corruption Scandals With Brazilian Roots Cascade Across Latin America”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ Andreoni, Manuela; Londoño, Ernesto; Darlington, Shasta (April 7, 2018). “Ex-President ‘Lula’ of Brazil Surrenders to Serve 12-Year Jail Term”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ “Another former Peruvian president is sent to jail, this time as part of growing corruption scandal”. Los Angeles Times. July 14, 2017. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Weiffen, Brigitte (December 1, 2020). “Latin America and COVID-19: Political Rights and Presidential Leadership to the Test”. Democratic Theory. 7 (2): 61–68. doi:10.3167/dt.2020.070208. ISSN 2332-8894. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good? (PDF). UNESCO. 2015. pp. 24, Box 1. ISBN 978-92-3-100088-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Report on World Social Situation 2013: Inequality Matters. United Nations. 2013. ISBN 978-92-1-130322-3. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Protección social inclusiva en América Latina. Una mirada integral, un enfoque de derechos [Inclusive social protection in Latin America. An integral look, a focus on rights]. United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (UNECLAC). March 2011. ISBN 9789210545556. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ Nutini, Hugo; Isaac, Barry (2009). Social Stratification in central Mexico 1500–2000. University of Texas Press. p. 55.

There are basically four operational categories that may be termed ethnic or even racial in Mexico today: (1) güero or blanco (white), denoting European and Near East extraction; (2) criollo (creole), meaning light mestizo in this context but actually of varying complexion; (3) mestizo, an imprecise category that includes many phenotypic variations; and (4) indio, also an imprecise category. These are nominal categories, and neither güero/blanco nor criollo is a widely used term (see Nutini 1997: 230). Nevertheless, there is a popular consensus in Mexico today that these four categories represent major sectors of the nation and that they can be arranged into a rough hierarchy: whites and creoles at the top, a vast population of mestizos in the middle, and Indians (perceived as both a racial and an ethnic component) at the bottom.

- ^ Seed, Patricia (1988). To Love, Honor, and Obey in Colonial Mexico: conflicts over Marriage Choice, 1574–1821. Stanford: Stanford University. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0-8047-2159-9.

- ^ Francisco H. Ferreira et al. Inequality in Latin America: Breaking with History?, The World Bank, Washington, D.C., 2004

- ^ Jones, Nicola; Baker, Hayley. “Untangling links between trade, poverty and gender”. ODI Briefing Papers 38, March 2008. Overseas Development Institute (ODI). Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Baten, Jörg; Mumme, Christina (2010). “Globalization and educational inequality during the 18th to 20th centuries: Latin America in global comparison”. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History. 28 (2): 279–305. doi:10.1017/S021261091000008X. hdl:10016/21558. S2CID 51961447.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 148f. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ Nations, United. “UNDP HDI 2020”. UNDP. Archived from the original on November 2, 2010. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ “GDP per Capita Ranking 2015 – Data and Charts”. Knoema. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ “Human Development Report 2011” (PDF). Table 3: Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ “Human Development Report 2011” (PDF). Table 5: Multidimensional Poverty Index. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ “ADULT AND YOUTH LITERACY: National, regional and global trends, 1985-2015” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ “Geoba.se: Gazetteer – The World – Life Expectancy – Top 100+ By Country (2016)”. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ “Homicide Statistics 2014”. Murder rate per 100,000 inhabitants. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Global Rankings”. Vision of Humanity. Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). July 24, 2020. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ “socio-economic policies” (PDF). dane.gov.co. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ “Statistic yearbook” (PDF). policica.gob.ni. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ “Life expectancy at birth, total”. The World Bank Group. May 30, 2024. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ “Life expectancy at birth, male”. The World Bank Group. May 30, 2024. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ “Life expectancy at birth, female”. The World Bank Group. May 30, 2024. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ “Global Metro Monitor 2014”. Brookings Institution. January 22, 2015. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ Andrews, George Reid. 1980. The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires, 1800–1900, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press

- ^ Gilberto Freyre. The Masters and the Slaves: A Study in the Development of Brazilian Civilization. Samuel Putnam (trans.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Thomas E. Skidmore. Black into White: Race and Nationality in Brazilian Thought. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

- ^ France Winddance Twine Racism in a Racial Democracy: The Maintenance of White Supremacy in Brazil,(1997) Rutgers University Press

- ^ “Reference for Welsh language in southern Argentina, Welsh immigration to Patagonia”. Bbc.co.uk. July 22, 2008. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ “The Welsh Immigration to Argentina”. 1stclassargentina.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ “Reference for Welsh language in southern Argentina, Welsh immigration to Patagonia”. Andesceltig.com. September 29, 2009. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ Meade, Teresa A. (2016). History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-118-77248-5.

- ^ “Christians”. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. December 18, 2012. Archived from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ “CIA – The World Factbook – Field Listing – Religions”. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Fraser, Barbara J., In Latin America, Catholics down, church’s credibility up, poll says Archived June 28, 2005, at the Library of Congress Web Archives Catholic News Service June 23, 2005

- ^ “The Global Religious Landscape” (PDF). Pewforum.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 25, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Alec Ryrie, “The World’s Local Religion” History Today (2017) online Archived September 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Religion in Latin America, Widespread Change in a Historically Catholic Region”. Pew Research Center. November 13, 2014. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ Burden, David K. La Idea Salvadora: Immigration and Colonization Politics in Mexico, 1821–1857. University of California, Santa Barbara, 2005.

- ^ Gutmann, Myron P., et al. “The demographic impact of the Mexican Revolution in the United States.” Austin: Population Research Center, University of Texas (2000)

- ^ Young, Julia G. “Cristero Diaspora: Mexican Immigrants, The US Catholic Church, and Mexico’s Cristero War, 1926–29.” The Catholic Historical Review (2012): 271–300.

- ^ Durand, Jorge, and Douglas S. Massey. “Mexican migration to the United States: A critical review.” Latin American Research Review 27.2 (1992): 3–42.

- ^ Sánchez-Albornoz, Nicolás. “The Spanish Exiles in Mexico and Beyond.” Exile and the politics of exclusion in the Americas (2012)

- ^ Adams, Jacqueline. Introduction: Jewish Refugees’ Lives in Latin America after Persecution and Impoverishment in Europe. Comparative Cultural Studies: European and Latin American Perspectives 11: 5–17, 2021

- ^ Wright, Thomas C., and Rody Oñate Zúniga. “Chilean political exile.” Latin American Perspectives 34.4 (2007): 31–49.

- ^ Bermudez, Anastasia. “The “diaspora politics” of Colombian migrants in the UK and Spain.” International Migration 49.3 (2011): 125–143.

- ^ Bertoli, Simone, Jesús Fernández-Huertas Moraga, and Francesc Ortega. “Immigration policies and the Ecuadorian exodus.” The World Bank Economic Review 25.1 (2011): 57–76.

- ^ Pedroza, L.; Palop, P.; Hoffmann, B. (2018). “Emigrant Policies in Latin America and the Caribbean: FLASCO-Chile” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 9, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF). 2022. School Meal Programs Around the World: Results from the 2021 Global Survey of School Meal Programs Archived January 29, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. GCNF: Seattle.

- ^ Welti, Carlos (2002). “Adolescents in Latin America: Facing the Future with Skepticism”. In Brown, B. (ed.). The World’s Youth: Adolescence in Eight Regions of the Globe ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521006058.

- ^ Jump up to:a b [BID/EDU Stakeholder Survey 1993/2003, February 8, 2011]

- ^ Latin America the Most Dangerous Region in terms of Violence, archived from the original on October 24, 2012, retrieved August 28, 2013

- ^ “Latin America: Crisis behind bars”. BBC News. November 16, 2005. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2010.

- ^ “Latin America Is the Murder Capital of the World”. The Wall Street Journal. September 20, 2018. Archived from the original on March 23, 2023. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ “A Year of Violence Sees Brazil’s Murder Rate Hit Record High”. The New York Times. August 10, 2018. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Intentional homicides (per 100,000 people)”. UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s International Homicide Statistics database. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2017.

- ^ “Map: Here are countries with the world’s highest murder rates”. UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s International Homicide Statistics database. June 27, 2016. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ “Crime Hinders Development, Democracy in Latin America, U.S. Says – US Department of State”. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008.

- ^ Briceno-Leon, R.; Villaveces, A.; Concha-Eastman, A. (2008). “”Understanding the uneven distribution of the incidence of homicide in Latin America””. International Journal of Epidemiology. 37 (4): 751–757. doi:10.1093/ije/dyn153. PMID 18653511. Archived from the original on June 1, 2010. International Journal of Epidemiology

- ^ “Life expectancy and Healthy life expectancy, data by country”. World Health Organization. December 4, 2022.

- ^ Onestini, Maria (February 6, 2011). “Water Quality and Health in Poor Urban Areas of Latin America”. International Journal of Water Resources Development. 27: 219–226. doi:10.1080/07900627.2010.537244. S2CID 154427438 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ “Chile abortion: Court approves easing total ban”. BBC News. August 21, 2017.

- ^ “Latin America and the Caribbean”. Center for Reproductive Rights. November 8, 2023. Retrieved November 10, 2023.

- ^ “Why we continue to march towards legal abortion in Argentina”. Amnesty International. August 8, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ “GAPD – The Global Abortion Policies Database – The Global Abortion Policies Database is designed to strengthen global efforts to eliminate unsafe abortion”. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “HIV and AIDS in Latin America the Caribbean regional overview”. Avert. July 21, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b García, Patricia J; Bayer, Angela; Cárcamo, César P (June 2014). “The Changing Face of HIV in Latin America and the Caribbean”. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 11 (2): 146–157. doi:10.1007/s11904-014-0204-1. ISSN 1548-3568. PMC 4136548. PMID 24824881.

- ^ “Homophobia and HIV”. Avert. July 20, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Miles to go—closing gaps, breaking barriers, righting injustices”. www.unaids.org. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ Silva-Santisteban, Alfonso; Eng, Shirley; de la Iglesia, Gabriela; Falistocco, Carlos; Mazin, Rafael (July 17, 2016). “HIV prevention among transgender women in Latin America: implementation, gaps and challenges”. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 19 (3Suppl 2): 20799. doi:10.7448/IAS.19.3.20799. ISSN 1758-2652. PMC 4949309. PMID 27431470.

- ^ “The N-11: More Than an Acronym” (PDF). Appendix II: Projections in Detail. Goldman Sachs Economic Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 31, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “GDP 2019, some Latin American countries”. IMF WEO Database. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ “Latin America production in 2020, by FAO”. Archived from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ “South American countries production in 2018, by FAO”. Archived from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Conheça os 3 países que desafiam o Brasil nas exportações de frango”. January 22, 2020. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “maiores exportadores de carne de frango entre os anos de 2015 e 2019”. May 30, 2019. Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “IBGE: rebanho de bovinos tinha 218,23 milhões de cabeças em 2016”. September 29, 2017. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Brasil é o 3º maior produtor de leite do mundo, superando o padrão Europeu em alguns municípios”. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “principais países produtores de carne suína entre 2017 e a estimativa para 2019”. July 23, 2019. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Argentina production in 2018, by FAO”. Archived from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Producción de carne y leche, por FAO”. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “mcs2021 /mcs2021-gold.pdf USGS Gold Production Statistics”. Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “Production statistics of USGS Silver” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “Copper production statistics for the USGS” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “Production statistics of USGS iron ore” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “Zinc production statistics from USGS” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “USGS Molybdenum Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS lithium production statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “USGS Lead Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Bauxite Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS tin production statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “Manganese production statistics from the USGS” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS antimony production statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Nickel Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Niobium Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS rhenium production statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS iodine production statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “ANM”. gov.br Agência Nacional de Mineração. July 31, 2023. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Brasil extrai cerca de 2 gramas de ouro por habitante em 5 anos”. R7.com. June 29, 2019. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “G1 > Economia e Negócios – NOTÍCIAS – Votorantim Metais adquire reservas de zinco da Masa”. g1.globo.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Nióbio: G1 visita em MG complexo industrial do maior produtor do mundo”. G1. December 12, 2019. Archived from the original on December 12, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Serviço Geológico do Brasil”. cprm.gov.br. Archived from the original on September 6, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Rio Grande do Sul: o maior exportador de pedras preciosas do Brasil”. Band.com.br. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Copper production in 2019 by USGS” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Iodine Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Rhenium Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “USGS Lithium Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “USGS Silver Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “USGS Salt Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Potash Product ion Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Sulfur Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Iron Ore Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “USGS Copper Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “USGS Gold Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “USGS Zinc Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “USGS Tin Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “USGS Boron Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 18, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Antimony Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Tungsten Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS ZincProduction Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Keith (June 21, 2013). “The state of mining in South America – an overview”. Miningweekly.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ “Anuário Mineral Brasileiro 2018”. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “La minería en México se reiniciará la próxima semana”. May 14, 2020. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “USGS Mercury Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Bismuth Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Manganese Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “USGS Phosphate Production Statistics” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “Colombian emeralds”. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “Gold production in Colombia”. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ “Silver production in Colombia”. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Production of Crude Oil including Lease Condensate 2019”. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Natural Gas production”. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Statistical Review of World Energy 2018”. Archived from the original on October 12, 2015. Retrieved June 26, 2021.

- ^ “Manufacturing, value added (current US$)”. Archived from the original on January 7, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Alimentos Processados | A indústria de alimentos e bebidas na sociedade brasileira atual”. alimentosprocessados.com.br. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Faturamento da indústria de alimentos cresceu 6,7% em 2019”. G1. February 18, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Indústria de alimentos e bebidas faturou R$699,9 bi em 2019”. Agência Brasil. February 18, 2020. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Produção nacional de celulose cai 6,6% em 2019, aponta Ibá”. Valor Econômico. February 21, 2020. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Sabe qual é o estado brasileiro que mais produz Madeira?”. October 9, 2017. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “São Mateus é o 6º maior produtor de madeira em tora para papel e celulose no país, diz IBGE”. G1. September 28, 2017. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Indústrias calçadistas em Franca, SP registram queda de 40% nas vagas de trabalho em 6 anos”. G1. July 14, 2019. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Digital, Agência Maya: Criação de Sites e Marketing. “Fenac – Centro de Eventos e Negócios | Produção de calçados deve crescer 3% em 2019”. fenac.com.br. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Abicalçados apresenta Relatório Setorial 2019”. abicalcados.com.br. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Exportação de Calçados: Saiba mais”. February 27, 2020. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Comércio, Diário do (January 24, 2020). “Minas Gerais produz 32,3% do aço nacional em 2019”. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “O novo mapa das montadoras, que agora rumam para o interior do País”. March 8, 2019. Archived from the original on March 8, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Indústria automobilística do Sul do Rio impulsiona superavit na economia”. G1. July 12, 2017. Archived from the original on July 19, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Indústria Química no Brasil” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Estudo de 2018” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Produção nacional da indústria de químicos cai 5,7% em 2019, diz Abiquim”. economia.uol.com.br. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Industria Textil no Brasil”. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Anuário CNT do transporte 2018”. Archived from the original on November 11, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Transporte en Cifras Estadísticas 2015”. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ “Carta Caminera 2017” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ CIA – The World Factbook Archived January 26, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. CIA World Factbook. Retrieved on December 20, 2010

- ^ Jump up to:a b Infraestructura Carretera Archived July 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes. México. Retrieved January 13, 2007

- ^ With data from The World Factbook

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Brasil tem 9 dos maiores aeroportos da América Latina”. October 29, 2018. Archived from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Ranking on the number of airports per country Archived January 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. CIA Factbook