“Despite a Q4 uptick, L.A. filming ends 2024 with second-lowest shoot days of the year, says FilmLA.”

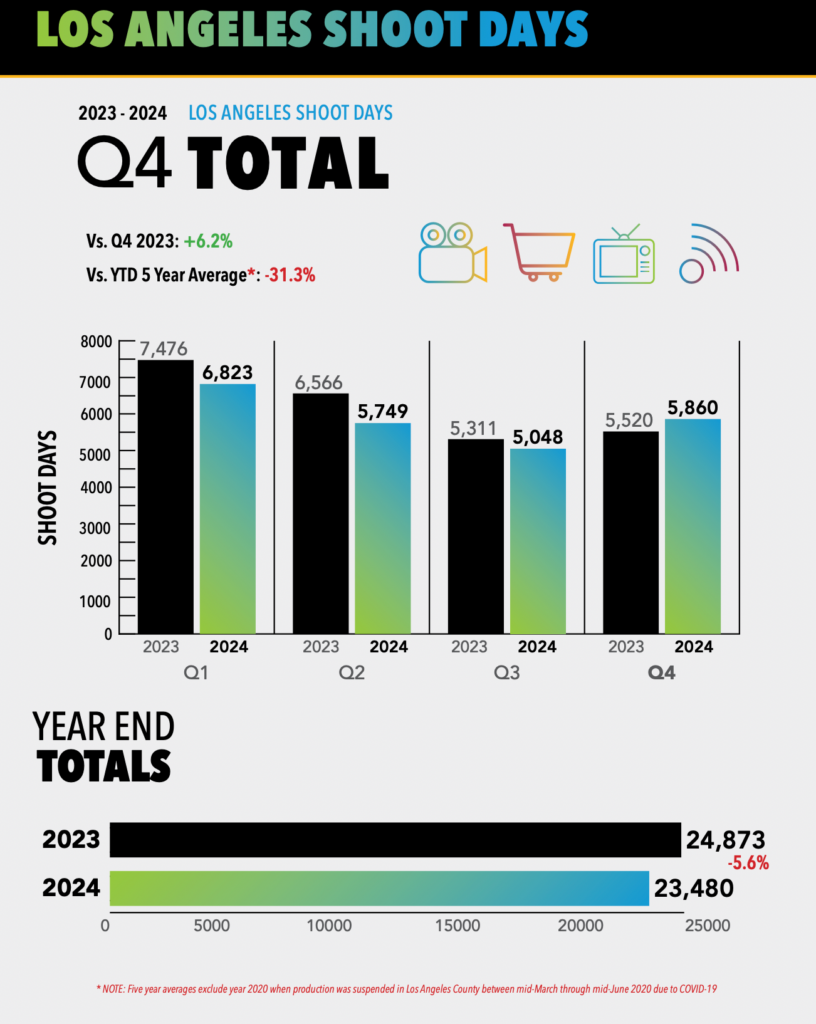

Filming in Los Angeles has shown signs of recovery, as production increased by approximately six percent in the last quarter of 2024 compared to the previous year. This uptick, from October to December, was observed across most types of production, excluding reality TV, which saw its ninth consecutive quarterly decline. The latest report from FilmLA, released on Wednesday, highlights that there were 5,860 shoot days in the final quarter of the year.

Despite this positive shift, the overall production numbers for the year remained historically low. Local shooting in Los Angeles in 2024 totaled 23,480 shoot days, marking the second-lowest level recorded by FilmLA since 2020 when filming was halted due to the pandemic.

The struggles in 2024 were attributed to multiple factors, including the long-term effects of runaway production. Many film and TV shows have continued to opt for locations with more generous tax incentives, contributing to the reduction in local filming. The recovery from the strikes, which impacted the industry throughout the year, was slower than anticipated, further exacerbating the situation. Additionally, the ongoing contraction of the entertainment industry played a role in the overall decline in local production.

While the last quarter’s increase is encouraging, it was not enough to significantly alter the course of a challenging year for L.A. film and TV production. The industry now faces the challenge of sustaining growth and regaining lost ground as it enters 2025.

The report from FilmLA does not factor in the impact of Los Angeles’ historic wildfires, which could further hamper production in the short term. These wildfires, which have intensified over recent years, have posed significant challenges to the industry, including disruptions to shooting schedules, locations, and crew safety. As a result, the ongoing wildfire season could exacerbate the already struggling production landscape in Los Angeles, potentially leading to additional delays and further declines in local filming in the immediate future.

In a statement, FilmLA President Paul Audley expressed deep concern about the widespread effects of the recent wildfires on Hollywood workers and related industries. He noted that many individuals in the entertainment sector, as well as those in ancillary industries, have been “directly affected by this tragedy.” Audley also emphasized that some iconic locations, cherished by audiences nationwide, may never return to the screen due to the devastation. He further highlighted the broader impact of the fires on the Greater Los Angeles area, stating, “No aspect of life in Greater Los Angeles is unaffected by recent fire events and the heartbreaking loss of lives, homes, businesses, and cherished community spaces.”

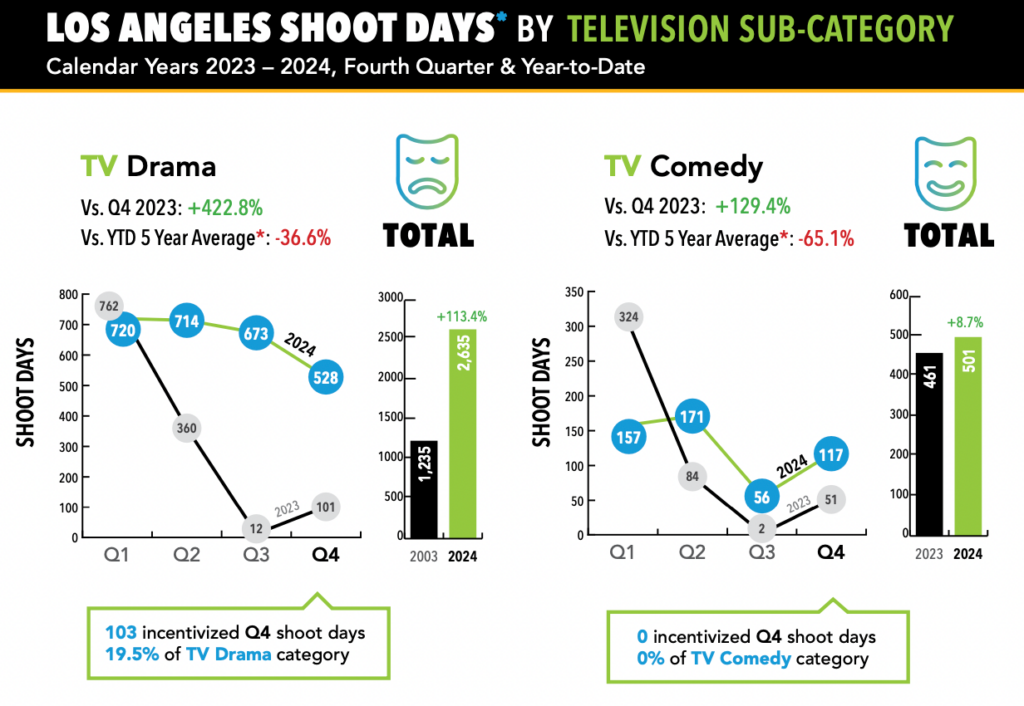

Despite gains in most major production categories during the last quarter of 2024, the TV sector saw a decline. TV production dropped by 6.5 percent, with 1,596 shoot days, which is just 53 percent of the five-year average. Reality TV, in particular, experienced a sharp 45.7 percent decline compared to the same period in 2023, significantly dragging down the entire TV category. TV dramas, however, saw some recovery, with 528 shoot days, although this still fell 36.6 percent below the five-year average.

A brighter spot emerged in feature film production, which saw a remarkable 82 percent increase compared to the previous year, reaching 589 shoot days. FilmLA analysts attribute this boost to increased independent film activity.

Amidst Los Angeles’ ongoing production slump, the focus has shifted to California’s film and TV tax incentive program. Earlier this month, Governor Gavin Newsom approved a budget proposal to significantly increase the state’s tax credit cap from $330 million to $750 million annually. If passed, the program would become the most generous state subsidy for the entertainment industry, trailing only Georgia, which does not have a cap on its annual subsidy offerings. This move is seen as a critical effort to revitalize local production and keep the industry competitive in the face of mounting challenges.

The success of California’s proposed expanded film and TV tax incentive program will depend largely on several key changes, including broadening the types of expenditures and categories of production that qualify for tax credits. One significant adjustment would be increasing the maximum amount of subsidies a single title can receive. Currently, California remains the only major film hub to exclude above-the-line costs—such as salaries for actors, directors, and producers—from qualifying for tax credits, which puts it at a disadvantage compared to other states with more flexible policies.

Many of the productions that choose to shoot in Los Angeles already benefit from tax incentives that encourage filming in California. Expanding the eligibility criteria and the overall subsidy amount could provide a much-needed boost to the local industry, incentivizing more productions to return to the region and counteracting the effects of the recent downturn. By making these adjustments, California could not only strengthen its position as a leading film hub but also help revitalize local filming activity amid ongoing challenges.

Courtesy: Doom External

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Gollust, Shelley (April 18, 2013). “Nicknames for Los Angeles”. Voice of America. Archived from the original on July 6, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ Barrows, H.D. (1899). “Felepe de Neve”. Historical Society of Southern California Quarterly. Vol. 4. p. 151ff. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ “This 1835 Decree Made the Pueblo of Los Angeles a Ciudad – And California’s Capital”. KCET. April 2016. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ “California Cities by Incorporation Date”. California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (DOC) on February 21, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ “About the City Government”. City of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files”. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 7, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ “US Census Bureau”. www.census.gov. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “QuickFacts: Los Angeles city, California”. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ “List of 2020 Census Urban Areas”. census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals: 2020-2023”. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 14, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ “Angelino, Angeleno, and Angeleño”. KCET. January 10, 2011. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ “Definition of Angeleno”. Merriam-Webster. May 16, 2023. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ “Total Gross Domestic Product for Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA (MSA)”. Federal Reserve Economic Data. Archived from the original on November 26, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ “Total Gross Domestic Product for Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA (MSA)”. fred.stlouisfed.org. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ “Total Gross Domestic Product for Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, CA (MSA)”. fred.stlouisfed.org. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^ Zip Codes Within the City of Los Angeles Archived July 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine – LAHD

- ^ “Slowing State Population Decline puts Latest Population at 39,185,000” (PDF). Department of Finance. State of California. May 2, 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 12, 2022. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ “America’s 10 most visited cities”, World Atlas, September 23, 2021. Archived June 14, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Estrada, William David (2009). The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space. University of Texas Press. pp. 15–50. ISBN 978-0-292-78209-9.

- ^ Preston, Cheryl (July 16, 2013). “Subterranean L.A.: The Urban Oil Fields”. The Getty Iris. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ Josh Rottenberg (June 24, 2024). “Hollywood’s exodus: Why film and TV workers are leaving Los Angeles”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Stephen Battaglio (May 15, 2024). “New York’s Studio Building Boom Poses Threat to LA’s Hollywood Production”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ Ivan Ehlers (May 21, 2024). “Opinion: Studio productions keep moving out of Los Angeles. We need to stop the bleeding”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ LaRocco, Lori Ann (September 24, 2022). “New York is now the nation’s busiest port in a historic tipping point for U.S.-bound trade”. CNBC. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ “Port of NYNJ Beats West Coast Rivals with Highest 2023 Volumes”. The Maritime Executive. Archived from the original on May 11, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ “Port of New York and New Jersey Remains US’ Top Container Port”. www.marinelink.com. December 28, 2022. Archived from the original on May 11, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Table 3.1. GDP & Personal Income”. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2018. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Roger Vincent (April 12, 2024). “Downtown L.A. is hurting. Frank Gehry thinks arts can lead a revival”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 14, 2024. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Settlement of Los Angeles”. Los Angeles Almanac. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ “Ooh L.A. L.A.” Los Angeles Times. December 12, 1991. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Pool, Bob (March 26, 2005). “City of Angels’ First Name Still Bedevils Historians”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Stein, David Allen (1953). “Los Angeles: A Noble Fight Nobly Lost”. Names. 1 (1): 35–38. doi:10.1179/nam.1953.1.1.35. ISSN 0027-7738.

- ^ Masters, Nathan (February 24, 2011). “The Crusader in Corduroy, the Land of Soundest Philosophy, and the ‘G’ That Shall Not Be Jellified”. KCET. Public Media Group of Southern California. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Masters, Nathan (May 6, 2016). “How to Pronounce “Los Angeles,” According to Charles Lummis”. KCET. Public Media Group of Southern California. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Lummis, Charles Fletcher (June 29, 1908). “This Is the Way to Pronounce Los Angeles”. Nebraska State Journal. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Harvey, Steve (June 26, 2011). “Devil of a time with City of Angels’ name”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Kenyon, John Samuel; Knott, Thomas Albert (1944). A Pronouncing Dictionary of American English. Springfield, Mass.: G. & C. Merriam. p. 260.

- ^ Buntin, John (2009). L.A. Noir: The Struggle for the Soul of America’s Most Seductive City. New York: Harmony Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-307-35207-1.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ^ Windsor Lewis, Jack (1990). “HappY land reconnoitred: the unstressed word-final -y vowel in General British pronunciation”. In Ramsaran, Susan (ed.). Studies in the Pronunciation of English: A Commemorative Volume in Honour of A.C. Gimson. Routledge. pp. 159–167. ISBN 978-1-138-92111-5. Archived from the original on May 18, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2023. Pages 166–167.

- ^ Bowman, Chris (July 8, 2008). “Smoke is Normal – for 1800”. The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Gordon J. MacDonald. “Environment: Evolution of a Concept” (PDF). p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

The Native American name for Los Angeles was Yang na, which translates into “the valley of smoke.”

- ^ Bright, William (1998). Fifteen Hundred California Place Names. University of California Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-520-21271-8. LCCN 97043147. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

Founded on the site of a Gabrielino Indian village called Yang-na, or iyáangẚ, ‘poison-oak place.’

- ^ Sullivan, Ron (December 7, 2002). “Roots of native names”. San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

Los Angeles itself was built over a Gabrielino village called Yangna or iyaanga’, ‘poison oak place.’

- ^ Willard, Charles Dwight (1901). The Herald’s History of Los Angeles. Los Angeles: Kingsley-Barnes & Neuner. pp. 21–24. ISBN 978-0-598-28043-5. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ^ “Portola Expedition 1769 Diaries”. Pacifica Historical Society. Archived from the original on November 13, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ Leffingwell, Randy; Worden, Alastair (November 4, 2005). California missions and presidios. Voyageur Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-89658-492-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Mulroy, Kevin; Taylor, Quintard; Autry Museum of Western Heritage (March 2001). “The Early African Heritage in California (Forbes, Jack D.)”. Seeking El Dorado: African Americans in California. University of Washington Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-295-98082-9. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Guinn, James Miller (1902). Historical and biographical record of southern California: containing a history of southern California from its earliest settlement to the opening year of the twentieth century. Chapman pub. co. p. 63. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Estrada, William D. (2006). Los Angeles’s Olvera Street. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3105-2. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ “Pio Pico, Afro Mexican Governor of Mexican California”. African American Registry. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ “Monterey County Historical Society, Local History Pages–Secularization and the Ranchos, 1826-1846”. mchsmuseum.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

- ^ Bauer, K. Jack (1993). The Mexican War, 1846-1848 (Bison books ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 184. OCLC 25746154.

- ^ Guinn, James Miller (1902). Historical and biographical record of southern California: containing a history of southern California from its earliest settlement to the opening year of the twentieth century. Chapman pub. co. p. 50. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Mulholland, Catherine (2002). William Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles. University of California Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-520-23466-6. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Kipen, David (2011). Los Angeles in the 1930s: The WPA Guide to the City of Angels. University of California Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-520-26883-8. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ “Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1900”. United States Census Bureau. June 15, 1998. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ “The Los Angeles Aqueduct and the Owens and Mono Lakes (MONO Case)”. American University. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ Reisner, Marc (1993). Cadillac desert: the American West and its disappearing water. Penguin. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-14-017824-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Basiago, Andrew D. (February 7, 1988), Water For Los Angeles – Sam Nelson Interview, The Regents of the University of California, 11, archived from the original on August 4, 2019, retrieved October 7, 2013

- ^ Annexation and Detachment Map (PDF) (Map). City of Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Creason, Glen (September 26, 2013). “CityDig: L.A.’s 20th Century Land Grab”. Lamag – Culture, Food, Fashion, News & Los Angeles. Los Angeles Magazine. Archived from the original on September 29, 2013. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ^ Weiss, Marc A (1987). The Rise of the Community Builders: The American Real Estate Industry and Urban Land Planning. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 80–86. ISBN 978-0-231-06505-4.

- ^ Buntin, John (April 6, 2010). L.A. Noir: The Struggle for the Soul of America’s Most Seductive City. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-307-35208-8. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ Young, William H.; Young, Nancy K. (March 2007). The Great Depression in America: a cultural encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-313-33521-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ “Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1930”. United States Census Bureau. June 15, 1998. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, pp.5–8, 14, 26, 36, 50, 60, 78, 94, 108, 122, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ^ Bruegmann, Robert (November 1, 2006). Sprawl: A Compact History. University of Chicago Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-226-07691-1. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Braun, Michael. “The economic impact of theme parks on regions” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2021. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ Jennings, Jay (February 26, 2021). Beverly Park: L.A.’s Kiddieland, 1943–74. Independently published. ISBN 979-8713878917.

- ^ Monkkonen, Paavo; Manville, Michael; Lens, Michael (2024). “Built out cities? A new approach to measuring land use regulation”. Journal of Housing Economics. 63. doi:10.1016/j.jhe.2024.101982. ISSN 1051-1377.

- ^ Hinton, Elizabeth (2016). From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America. Harvard University Press. pp. 68–72. ISBN 9780674737235. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- ^ Hafner, Katie; Lyon, Matthew (August 1, 1999). Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins Of The Internet. Simon and Schuster. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-684-87216-2. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Vronsky, Peter (2004). Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters. Penguin. p. 187. ISBN 0-425-19640-2.

- ^ Woo, Elaine (June 30, 2004). “Rodney W. Rood, 88; Played Key Role in 1984 Olympics, Built Support for Metro Rail”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Zarnowski, C. Frank (Summer 1992). “A Look at Olympic Costs” (PDF). Citius, Altius, Fortius. 1 (1): 16–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Rucker, Walter C.; Upton, James N.; Hughey, Matthew W. (2007). “Los Angeles (California) Riots of 1992”. Encyclopedia of American race riots. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 376–85. ISBN 978-0-313-33301-9. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Stan (April 25, 2012). “Riot anniversary tour surveys progress and economic challenges in Los Angeles”. CNN. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ^ Reich, Kenneth (December 20, 1995). “Study Raises Northridge Quake Death Toll to 72”. Los Angeles Times. p. B1. Archived from the original on December 13, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ “Rampart Scandal Timeline”. PBS Frontline. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Orlov, Rick (November 3, 2012). “Secession drive changed San Fernando Valley, Los Angeles”. Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ “Karen Bass elected mayor, becoming first woman to lead L.A.” Los Angeles Times. November 16, 2022. Archived from the original on November 17, 2022. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ Cleave, Iona; Ibbetson, Connor James (January 9, 2025). “Worst fire in LA’s history leaves entire neighbourhoods in ruins”. The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved January 16, 2