Soviet Union

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, cinema in the Soviet Union transformed into a groundbreaking art form and a powerful tool of communication. The nation’s most famous director, Sergey Eisenstein, brought to life monumental works such as Battleship Potemkin and Ivan the Terrible, integrating new editing techniques with the Marxist dialectic. Eisenstein, under the tutelage of Lev Kuleshov at Moscow’s All-Union Institute of Cinematography, embraced Kuleshov’s montage technique, which involved rapid, evocative editing to convey complex ideas. This style became a foundation for Soviet cinema, particularly in Eisenstein’s “Odessa Steps” sequence in Battleship Potemkin, which used montage to stir emotions and deliver messages with unprecedented intensity.

Lenin

Lenin, recognizing cinema’s influence on both illiterate and non-Russian-speaking populations, supported the expansion of film as a medium of “agitprop” (agitation and propaganda). Soviet filmmakers, like Vsevolod Pudovkin with his film Mother (1926), used montage to explore revolutionary themes, reaching audiences far and wide. Meanwhile, Dziga Vertov’s “kino-glaz” (film-eye) theory pushed documentary filmmaking toward capturing raw reality, shaping Soviet cinema’s documentary tradition.

The Soviet Union’s strict adherence to Socialist Realism in the 1930s and 1940s aimed to glorify the Soviet state, but a few films still stood out artistically. The Cranes Are Flying and Ballad of a Soldier, for example, received acclaim, even within the confines of state-imposed realism. Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, directors like Andrey Tarkovsky and Sergey Paradzhanov emerged, creating films of poetic beauty and philosophical depth, such as Andrey Rublev and The Colour of Pomegranates.

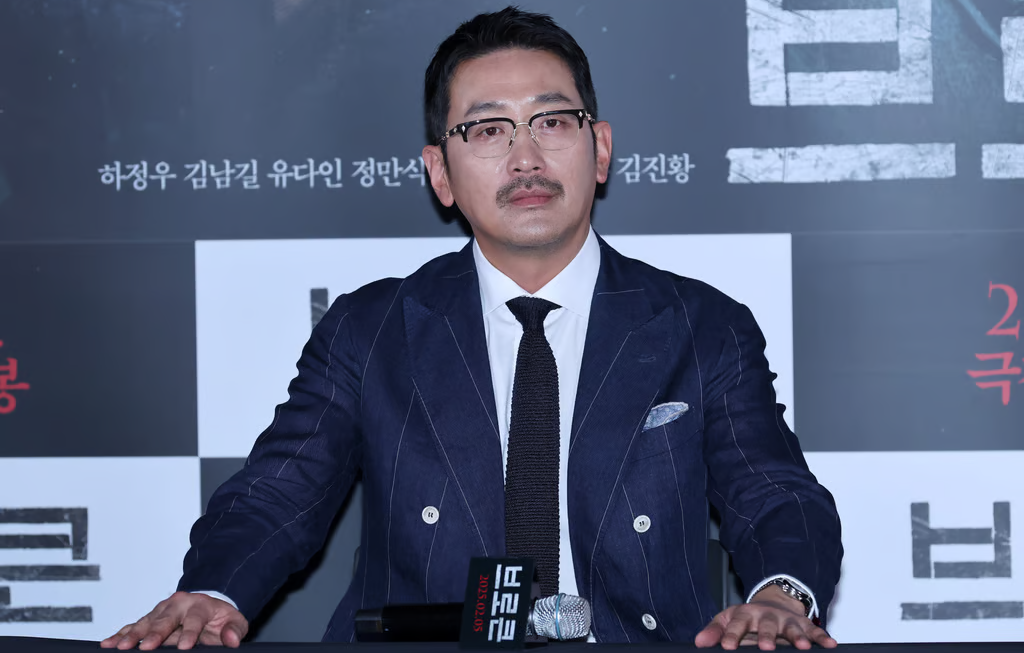

Vladimir Menshov

By the 1980s and 1990s, Russian cinema faced challenges due to reduced state subsidies and a weakened distribution system, which led to an influx of Western films. However, Russian filmmakers continued to achieve international success. Notably, Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears by Vladimir Menshov and Burnt by the Sun by Nikita Mikhalkov won Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film. Aleksandr Sokurov’s experimental Russian Ark, a single-take masterpiece, was also met with global acclaim.

Despite the struggle for financial support and resources, Russian filmmakers preserved their unique cinematic vision. Russian cinema had evolved from a tool of propaganda to an art form that resonated globally, producing works that explored the human condition in ways that were timeless and universal.

Bolshevik Revolution

Russian cinema has undergone profound transformations, from the revolutionary days following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution to the post-Soviet era. Throughout its history, the medium has reflected both the changing political landscapes of Russia and the artistic exploration of filmmakers seeking to express their visions.

Early Soviet Cinema and Revolutionary Filmmaking

The Soviet Union, in the years after the 1917 revolution, became a hotbed of cinematic experimentation. Directors like Sergey Eisenstein, Lev Kuleshov, and Vsevolod Pudovkin revolutionized film through their innovative use of montage—a technique where the arrangement of shots creates new meaning through their juxtaposition. The world’s first film school, the All-Union Institute of Cinematography in Moscow, became the hub for these revolutionary filmmakers. Supported by Lenin, who saw cinema as a vital tool for spreading revolutionary ideology, Soviet cinema adopted the art of agitprop (agitation and propaganda), aiming to educate and mobilize the masses, particularly the illiterate and non-Russian-speaking populations.

Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) remains one of the most influential films in history, demonstrating the power of montage in conveying revolutionary themes. Another seminal work by Eisenstein, Ivan the Terrible (released in two parts, 1944 and 1958), explored the complex psychology of the Russian Tsar, blending historical narrative with symbolic imagery.

Eisenstein was profoundly influenced by his teacher Lev Kuleshov, whose Kuleshov Effect demonstrated the psychological impact of editing. Kuleshov’s approach to montage emphasized how viewers’ interpretations of a scene could change based on its surrounding shots. Another of Kuleshov’s students, Vsevolod Pudovkin, built on these ideas with his monumental film Mother (1926), a powerful depiction of class struggle.

At the same time, Dziga Vertov pioneered the kino-glaz (“film-eye”) theory, which promoted the idea that the camera was not just a passive observer but an active tool for uncovering truth. His landmark work Man with a Movie Camera (1929) remains a triumph of experimental film, using innovative techniques to explore the nature of film and reality.

Socialist Realism and Post-War Cinema

In the years that followed, Soviet cinema was increasingly subject to the strictures of Socialist Realism under Joseph Stalin. This form of filmmaking, which was imposed after the 1930s, prioritized works that glorified the Soviet state, the working class, and socialist ideals while avoiding any form of dissent or complexity. Films were often focused on heroism, socialist optimism, and the collective spirit, with little room for individualism or critique of the government.

However, some films managed to achieve artistic success within these constraints. Notable examples include The Cranes Are Flying (1957), directed by Mikhail Kalatozov, which poignantly portrays the emotional impact of World War II on Soviet civilians, and Ballad of a Soldier (1959) by Grigory Chukhrai, a poignant tale of a young soldier’s brief visit home during the war.

In the 1950s and 1960s, there were also successful adaptations of Western literary works, such as Hamlet (1964) and King Lear (1971), directed by Grigory Kozintsev. These adaptations were praised for their intellectual depth and visually striking interpretations of Shakespeare.

The Golden Age: Tarkovsky and the 1960s-1970s

The 1960s and 1970s marked a golden age for Russian cinema, as directors like Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergey Paradzhanov gained international acclaim. Tarkovsky’s films, such as Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Andrei Rublev (1966), Solaris (1971), and Nostalgia (1983), were known for their deeply philosophical explorations of time, memory, and spirituality. Tarkovsky’s unique style, characterized by long takes, symbolic imagery, and a focus on the metaphysical aspects of human existence, made him one of the most influential filmmakers of his time.

Meanwhile, Sergey Paradzhanov, a Georgian-born Armenian director, made a significant impact with his visually stunning films like Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964) and The Colour of Pomegranates (1969). His works are celebrated for their rich, dreamlike visuals and their blending of myth, history, and folklore. Paradzhanov’s use of non-linear storytelling and symbolic imagery placed him in the ranks of the greats of world cinema.

The Decline of Soviet Cinema: The 1980s-1990s

In the 1980s and 1990s, Russian cinema faced a crisis following the collapse of the Soviet Union. With the end of state subsidies and the dissolution of the state-controlled film distribution system, Russian filmmakers faced severe financial challenges. This period saw a rise in Western films dominating Russian theaters, while the domestic film industry struggled to find a foothold in a rapidly changing media landscape.

Despite these challenges, several Russian filmmakers continued to achieve international recognition. Vladimir Menshov’s Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears (1979) and Nikita Mikhalkov‘s Burnt by the Sun (1994) both won Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film, showcasing the continued artistic merit of Russian cinema.

Andrey Konchalovsky, who worked both in Russia and internationally, created a variety of films, including Runaway Train (1985) and House of Fools (2002), which showcased his adaptability across genres and his exploration of human psychology and conflict.

One of the most notable developments in post-Soviet Russian cinema was the emergence of Aleksandr Sokurov in the late 1990s. Sokurov’s films, such as Mother and Son (1997) and Russian Ark (2002), which was shot in a single take, garnered international acclaim for their philosophical depth and technical innovation. Russian Ark was particularly groundbreaking in its seamless, uninterrupted tracking shot through the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, blending history and art in a unique cinematic experience.

Modern Russian Cinema

In the post-Soviet era, Russian cinema has continued to evolve, albeit under economic pressures and the challenges of competing with Hollywood. However, Russian filmmakers have continued to find innovative ways to express their art. Films like Leviathan (2014), directed by Andrey Zvyagintsev, have garnered international acclaim for their portrayal of corruption and social decay in modern Russia.

Andrey Zvyagintsev’s films, including The Return (2003) and Loveless (2017), continue to receive critical praise for their stark depictions of modern Russian life, social alienation, and the human condition. These films often touch on themes of morality, societal dysfunction, and existential despair, presenting a bleak view of contemporary Russia that resonates globally.

Russian cinema has continued to thrive despite the challenges of state censorship and financial difficulties, producing films that offer a profound look at both the country’s past and present. It is a testament to the creativity and resilience of Russian filmmakers, who have used cinema not just to entertain, but to offer profound insights into the human experience.

Courtesy:Самбурская

References

- ^ “Australia’s Sweet Country Wins Best Feature Film at 11th Asia Pacific Screen Awards”. 23 November 2017.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: The Banishment”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 18 December 2009.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Elena”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ Leffler, Rebecca (21 May 2011). “Un Certain Regard Announces Top Prizes (Cannes 2011)”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ “2014 Official Selection”. Cannes. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ “Awards 2014 : Competition”. Cannes. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ “The Latest: Cannes Honors ‘A Gentle Night,’ ‘Loveless'”. US News. 28 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ “Harvey Weinstein’s Shadow Hangs Over London Film Festival Awards”. What’s Worth Seeing. 14 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ “The Golden Unicorn Awards Honour Film Makers For Second Year Running”. Ikon London Magazine. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ Croll, Ben (3 December 2023). “Andrey Zvyagintsev Will Tackle Oligarch Drama ‘Jupiter’ With New Creative Vision: ‘I’m Hoping to Start From Scratch'”. Variety. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ “На “Кинотавре” показали счастливых гастарбайтеров”. MK. 4 June 2014.

- ^ “Любимые женщины режиссера Звягинцева”. Komsomolskaya Pravda. 4 February 2015.

- ^ “Андрей Звягинцев: “Если я и шпион, то только русский””. Izvestia. 20 February 2015.

- ^ “Дурной сон госзаказа”. Kommersant. 26 October 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Началось все с вакцины Спутник”. DTF. 12 May 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “”Ходить самостоятельно я не могу”: Андрей Звягинцев рассказал, как борется за свою жизнь”. Teleprogramma. 13 May 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “”Аня, звони в скорую, я умираю”: режиссер Андрей Звягинцев рассказал, как боролся за жизнь после вакцинации и болезни”. NGS. 13 May 2022.

- ^ “Лучшие российские сериалы первой половины 2022 года

- Peter Rollberg (2016). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 489–491. ISBN 978-1442268425.

- ^ “13th Moscow International Film Festival (1983)”. MIFF. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Dark Eyes”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: Burnt by the Sun”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- ^ “‘Burnt By the Sun’ Wins Foreign Film Oscar”. AP NEWS. 27 March 1995. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ “Berlinale: 1996 Juries”. berlinale.de. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ “Festival de Cannes: The Barber of Siberia”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ “Hollywood Reporter: Cannes Lineup”. hollywoodreporter. Archived from the original on 22 April 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ^ “”Цитадель” Михалкова выдвинута на “Оскар””. Penza. 19 September 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ Михалков: “Я приехал, чтобы поддержать сохранение Косова в составе Сербии”[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ragozin, Leonid (21–27 January 2008). “Точка невозврата”. Russian Newsweek. 4 (178). Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

Михалков прищурился еще хитрее и нанес главный риторический удар: «Потому что православие – это основная сила, противостоящая культурному и интеллектуальному макдоналдсу»…Вдруг из зала раздался провокационный вопрос: «А что лучше – макдоналдс или сталинизм?» – «Ну это кому как», – ответил сын лауреата Сталинской премии.

- ^ Великое интервью о великом кино Archived 26 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Kommersant.ru. 11 May 2010.

- ^ “Никита Михалков сдал мигалку”. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Bayer, Alexei (24 March 2008). “Sympathy for the devil”. The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- ^ НАМ НЕ НРАВИТСЯ Archived 12 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine – manifesto of those starting new union

- ^ “Opponents of Nikita Mikhalkov to Found Alternative Union of Cinematographers”. Russia-ic.com. 19 April 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ “Director Nikita Mikhalkov Speaks Out After Ukraine Ban”. The Hollywood Reporter. 31 August 2015.

- ^ “Кінорежисер Михалков створює загрозу нацбезпеці України – СБУ”.

- ^ “Никита Михалков – Дождю: “Коллективных писем я не подписываю”. Как режиссер вступился за украинского коллегу Сенцова”. 29 June 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Михалков: признание РФ Луганской и Донецкой народных республик было единственным выходом” [Mikhalkov: Russia’s recognition of the Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics was the only way out] (in Russian). TASS. 25 February 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ “COUNCIL DECISION (CFSP) 2022/2477 of 16 December 2022”. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ “Zelensky imposes sanctions against 119 Russian cultural and sports figures”. Meduza. 7 January 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ “Ukraine imposes sanctions on Russian, pro-Russian celebrities”. The Kyiv Independent. 7 January 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Solnechnyy udar (Sunstroke) at IMDb.com

- Larsen, Susan (Autumn 2003). “National Identity, Cultural Authority, and the Post-Soviet Blockbuster: Nikita Mikhalkov and Aleksei Balabanov”. Slavic Review. 62 (3): 491