US President-elect Donald Trump has called on Nato’s European members to spend 5% of their national incomes on defence.

NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) is a military alliance established in 1949 with the goal of ensuring the security and defense of its member countries. The alliance was founded on the principle of collective defense, meaning that an attack on one NATO member is considered an attack on all, as outlined in Article 5 of the NATO treaty. Over the years, NATO has grown to include 30 member countries, primarily from Europe and North America, though it has expanded its reach and influence globally.

The current defense spending target set by NATO for its member countries is 2% of their GDP (Gross Domestic Product). However, there are increasing calls for member nations to raise this target, especially in light of growing global security threats, including Russia’s aggressive actions in Ukraine and rising tensions with China.

Currently, many NATO countries are struggling to meet the 2% defense spending target, and several are significantly below it. But in response to the increasing demands of global security, NATO has been encouraging its members to raise defense budgets. Some nations have already committed to higher spending, while others are under pressure to meet the alliance’s expectations.

The current defense spending by NATO members stands at about 2%, but recent discussions have raised the possibility of doubling this amount to enhance military capabilities and improve deterrence against adversaries. This proposed increase reflects the growing urgency of modernizing defense systems, bolstering readiness, and maintaining a strong collective defense posture.

The decision to double the defense spending target is part of NATO’s broader strategy to address contemporary security challenges, ranging from conventional military threats to cyber attacks, terrorism, and other emerging risks. This shift would ensure that NATO remains a strong and adaptable alliance capable of responding to various global security challenges in the years ahead.

As NATO members consider increasing defense budgets, the alliance’s role in shaping global security and maintaining peace will be under close scrutiny. Some members are already making significant investments in defense, but the overall increase in funding will likely be gradual, with an emphasis on long-term strategic goals and capabilities.

NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte has urged member countries to adopt a “wartime mindset” and increase military spending in response to the growing security threats facing the alliance. Rutte’s call comes at a time when global tensions are escalating, particularly in Eastern Europe, where Russia’s actions in Ukraine have raised alarms within NATO.

The concept of a “wartime mindset” emphasizes the need for countries to prioritize defense capabilities, strengthen military readiness, and focus on deterrence in the face of increasingly sophisticated and diverse threats. Rutte highlighted that NATO must adapt to a rapidly changing security landscape and be prepared for potential conflicts, whether conventional, hybrid, or cyber in nature.

Under this new approach, NATO members are expected to commit more resources to defense, ensuring that the alliance remains capable of responding to any threat swiftly and effectively. This includes modernizing military technologies, improving training and readiness, and reinforcing the strategic importance of collective defense.

Rutte’s message aligns with NATO’s long-standing principle of collective defense, where an attack on one member is considered an attack on all. The increased military spending is viewed as crucial to maintaining this principle and ensuring the safety of the alliance’s 30 member nations.

While many NATO countries are already under pressure to meet the 2% defense spending target, the call for higher spending reflects a growing recognition that defense budgets need to be significantly enhanced to address the evolving security challenges of the 21st century. The goal is to ensure that NATO remains a strong and capable military alliance, prepared to face the challenges posed by global instability.

What is Nato and why was it set up?

NATO, or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, was established on April 4, 1949, in Washington, D.C., as a collective defense alliance aimed at countering the growing threat of Soviet expansion and ensuring the security of its member states in the aftermath of World War II. The founding members included 12 countries:

- Belgium

- Canada

- Denmark

- France

- Iceland

- Italy

- Luxembourg

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Portugal

- United Kingdom

- United States

The alliance was founded on the principle that an attack on one member would be considered an attack on all, as outlined in Article 5 of the NATO treaty. This principle of collective defense has been the cornerstone of NATO’s mission and has helped to deter aggression against its members.

Since its founding, NATO has expanded several times to include countries from Europe, the Balkans, and beyond, bringing its current membership to 30 nations. The organization’s role has evolved over the years, from its original mission of containing Soviet influence during the Cold War to addressing a wide range of global security challenges, including terrorism, cyber threats, and regional conflicts.

NATO remains a powerful military alliance, committed to the defense of its members and the promotion of stability and peace worldwide. Its members continue to collaborate on defense strategy, military interoperability, and humanitarian efforts to address contemporary security issues.

NATO’s primary purpose, in its early years, was to prevent the expansion of the Soviet Union and its communist ideologies across Europe during the Cold War. The alliance’s founding members aimed to protect democratic nations from the spread of communism, particularly in Europe, where tensions between East and West were escalating.

A core principle of NATO is collective defense. According to Article 5 of the NATO Treaty, if one member state is attacked, it is considered an attack on all members, and the alliance is bound to help defend the targeted country. This principle ensures that NATO members stand united in the face of aggression.

Although NATO does not have its own permanent standing army, member countries contribute troops and resources for collective military action. In response to crises, NATO can mobilize forces from member states to take collective military action.

For example, NATO played a significant role in supporting the United Nations during the conflict in the former Yugoslavia between 1992 and 2004. NATO forces carried out air strikes, peacekeeping operations, and humanitarian missions, helping to stabilize the region after the violent breakup of Yugoslavia.

Additionally, NATO coordinates military plans and conducts joint military exercises among its member nations. These exercises help ensure interoperability among the various armed forces and prepare the alliance for potential security threats. By participating in these exercises, NATO members enhance their readiness to respond collectively to various challenges, from conventional warfare to peacekeeping and crisis management.

Which countries are Nato members?

NATO currently comprises 32 member countries from across Europe and North America. The alliance began with 12 founding members in 1949, which included the United States, Canada, and several European nations such as the UK, France, and Italy. Since then, NATO has expanded significantly, especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, many former Eastern Bloc countries sought membership in NATO, viewing it as a way to secure their sovereignty, strengthen their security, and distance themselves from Russian influence. This led to a series of NATO enlargements throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

Countries that joined NATO after 1991 include:

- Poland

- Hungary

- Czech Republic

- Slovakia

- Romania

- Bulgaria

- Albania

- Lithuania

- Latvia

- Estonia

These countries, once part of the Soviet sphere of influence, now form a significant part of NATO’s eastern flank. Their accession has not only expanded NATO geographically but also reinforced the alliance’s role in maintaining stability and security in Europe, especially in light of Russia’s growing influence and actions.

The most recent members to join include North Macedonia in 2020 and Finland in 2023. Sweden is also in the process of joining NATO, which would further extend the alliance’s reach in Northern Europe. Each new addition to NATO reflects the ongoing desire of European countries to align with the West and ensure collective defense against any potential threats.

Finland, which shares a 1,340 km (832-mile) land border with Russia, officially became a NATO member in April 2023. Sweden followed suit, joining the alliance in March 2024. Both countries had maintained a policy of neutrality for decades but applied for NATO membership in May 2022, shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Their decision to join NATO was driven by concerns about regional security and the desire to align with Western defense structures in the face of growing Russian aggression.

The accession of Finland and Sweden marks a significant shift in the security landscape of Northern Europe, enhancing NATO’s eastern defenses and reinforcing the alliance’s collective defense principle.

Meanwhile, other countries such as Ukraine, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Georgia have also expressed their interest in joining NATO. Ukraine’s membership aspirations have gained significant attention due to its ongoing conflict with Russia, with many NATO members providing military and economic support to Ukraine in its fight against Russian forces. Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as Georgia, have also sought closer ties with NATO, though their accession processes are more complex due to internal political dynamics and the regional security situation.

The potential enlargement of NATO reflects the alliance’s ongoing evolution in response to new security challenges, particularly the ongoing Russian threat in Europe. However, the inclusion of countries like Ukraine may take time, as NATO has maintained that new members must meet specific political, military, and institutional standards.

Why isn’t Ukraine a Nato member?

Russia has consistently opposed the idea of Ukraine joining NATO, citing concerns that the alliance’s expansion would bring NATO forces dangerously close to its borders. Moscow views the potential membership of Ukraine as a direct threat to its sphere of influence and national security, especially considering NATO’s collective defense principle, which could lead to the alliance’s military presence on Russia’s doorstep.

In 2008, despite Russia’s opposition, NATO declared that Ukraine could eventually become a member, signaling support for Ukraine’s aspirations to join the alliance. However, NATO’s promise did not immediately translate into membership, as Ukraine was not yet in a position to meet the necessary political and military criteria. Over the following years, Ukraine focused on strengthening its ties with NATO, undergoing reforms, and increasing cooperation with the alliance, particularly through joint military exercises and reforms to its defense sector.

Ukraine’s aspirations to join NATO became more urgent following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the subsequent conflict in eastern Ukraine. These events led Ukraine to seek stronger security guarantees and military support from the West, culminating in its formal application for NATO membership in 2022.

NATO’s decision on Ukraine’s membership remains a contentious issue, particularly in light of the ongoing war with Russia, which views NATO’s expansion as a provocation and a challenge to its geopolitical interests.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky urged NATO to fast-track Ukraine’s membership, emphasizing the need for immediate security guarantees as the country faced an unprecedented military threat from its neighbor. Zelensky’s appeal reflected Ukraine’s desperation for stronger protection against Russian aggression, especially as the war intensified and Ukrainian cities were targeted.

NATO, however, reaffirmed its long-standing position that while Ukraine’s eventual membership was still a possibility, the process would not be expedited during the ongoing conflict. Then-NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg acknowledged that Ukraine could potentially join the alliance in the long term but stated that NATO would not extend full membership to Ukraine until after the war had concluded. This decision was grounded in concerns over the risks of direct confrontation between NATO forces and Russia, which could escalate the conflict into a broader war.

The delay in NATO membership for Ukraine has been a point of contention, as the country continues to seek stronger assurances and support from the West. While NATO has provided military aid and political backing to Ukraine, the question of membership remains unresolved amid the ongoing conflict.

How much do Nato members spend on defence?

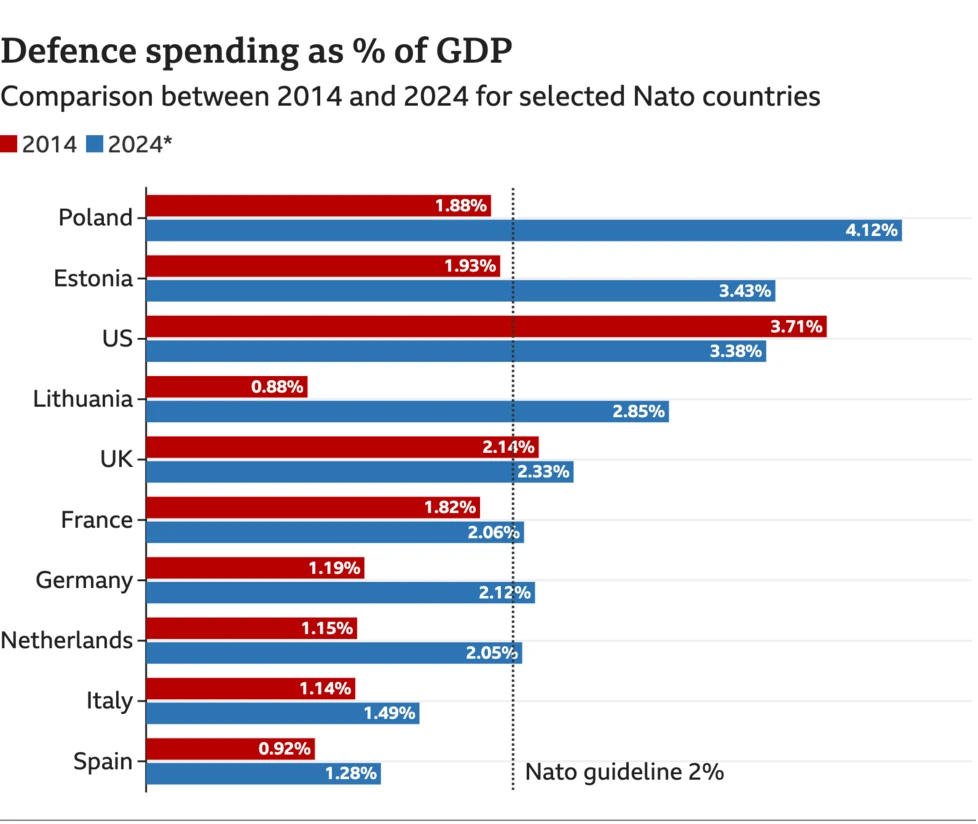

NATO currently requires each of its member countries to allocate at least 2% of their national income (GDP) to defense spending, a target that has been a key element of the alliance’s efforts to ensure collective security and military readiness. This defense spending commitment was reinforced after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, as NATO sought to strengthen its deterrence capabilities in the face of growing security concerns.

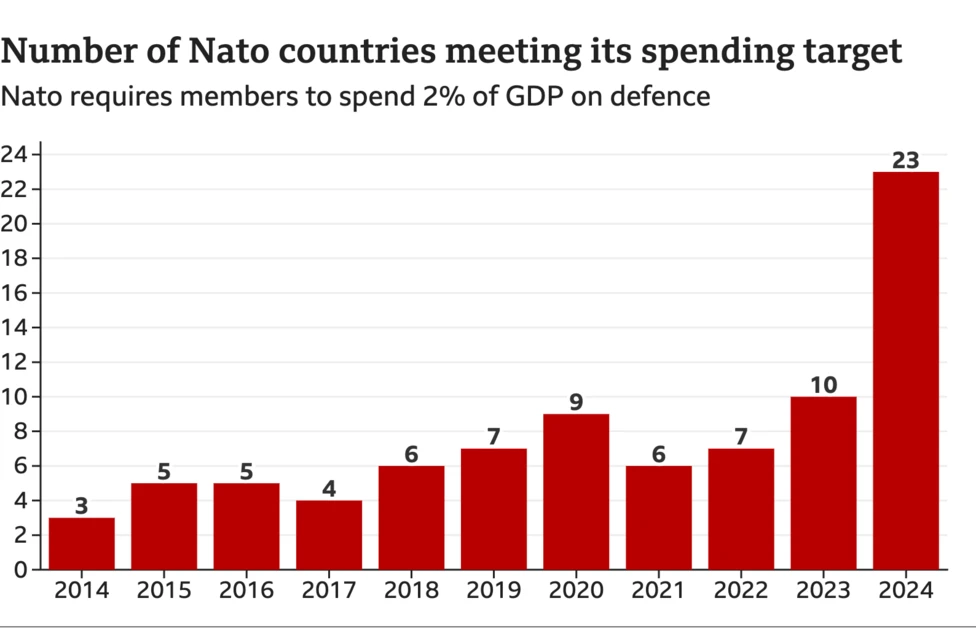

In 2024, it is estimated that 23 out of NATO’s 32 member countries met this 2% defense spending target, a significant increase from just three countries in 2014. This shift reflects the growing realization among NATO members that increased defense spending is crucial to addressing emerging security challenges, including those posed by Russia, as well as enhancing overall military preparedness and capabilities.

The increase in defense spending among NATO members is also tied to the alliance’s updated strategic priorities, which include bolstering deterrence, improving defense capabilities, and responding to potential threats in both Europe and beyond. The growing alignment of NATO members with the 2% target is seen as a clear sign of solidarity within the alliance, as well as a commitment to maintaining a strong and unified defense posture in an increasingly volatile geopolitical environment.

The countries that allocate the largest share of their GDP to defense spending within NATO are typically the United States and those located near Russia, such as Poland and the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania). These nations, given their proximity to Russia, view robust defense spending as critical to safeguarding their security in light of Russia’s aggressive actions, especially since the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

In July 2024, UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer announced that the United Kingdom would increase its defense spending to 2.5% of GDP. This decision is part of the UK’s response to escalating global security threats and aligns with NATO’s overall goal of strengthening collective defense capabilities. The UK’s pledge to boost defense spending underscores its commitment to NATO and its role in regional and global security, as well as a recognition of the evolving strategic landscape, particularly in the wake of Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

As NATO continues to emphasize the need for adequate defense budgets, the UK’s increase in defense spending highlights the broader trend among member nations to bolster their military capabilities and support the alliance’s efforts to maintain peace and stability in Europe and beyond.

In December 2024, NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte emphasized that member states would need to “shift to a wartime mindset” and significantly increase defense spending, well beyond the current 2% target. This shift reflects the growing security challenges faced by NATO, particularly in the context of Russia’s actions in Ukraine and global instability. Rutte’s comments align with NATO’s ongoing push to enhance its collective defense capabilities, encouraging member countries to invest more in their militaries to ensure readiness for potential conflicts.

Former U.S. President Donald Trump, during his first term, was a vocal advocate for higher defense spending among NATO members. In 2018, he called on all NATO countries to commit 4% of their GDP to defense. This demand reflected his belief that European NATO members should bear a larger share of the alliance’s defense burden. Trump has continued to push for higher defense spending from European nations, and in January 2025, he urged NATO’s European members to spend 5% of their GDP on defense, asserting that “they can all afford it.”

While campaigning for his second term as president, Trump made controversial remarks suggesting he might encourage Russia to attack NATO countries that fail to meet defense spending targets. These comments were widely condemned, including by the White House and former NATO chief Jens Stoltenberg, who emphasized the importance of unity and collective defense within the alliance. Trump’s rhetoric underscored the ongoing debate within NATO about defense contributions, but also highlighted the differing approaches to security within the alliance, with some members seeking stronger commitments to defense spending and others grappling with the economic and political implications of increased military expenditure.

Courtesy: WION

References

- ^ “The NATO Russian Founding Act | Arms Control Association”. www.armscontrol.org. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Benson, Brett V. (2012). Constructing International Security: Alliances, Deterrence, and Moral Hazard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1107027244.

- ^ “Russia says deployment of EU mission in Armenia to ‘exacerbate existing contradictions'”.

- ^ Jump up to:a b RAND, Russia’s Hostile Measures: Combating Russian Gray Zone Aggression Against NATO in the Contact, Blunt, and Surge Layers of Competition (2020) online

- ^ “Twenty Years of Russian “Peacekeeping” in Moldova”. Jamestown. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ “President of Russia”. 2 September 2008. Archived from the original on 2 September 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew; Erlanger, Steven (27 February 2014). “Gunmen Seize Government Buildings in Crimea”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Ellyatt, Holly (24 February 2022). “Russian forces invade Ukraine”. CNBC. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ “Russia joins war in Syria: Five key points”. BBC News. 1 October 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ “Russia blocks trains carrying Kazakh coal to Ukraine | Article”. 5 November 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Russia suspends its mission at NATO, shuts alliance’s office”. AP. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Chernova, Anna; Fox, Kara. “Russia suspending mission to NATO in response to staff expulsions”. CNN. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Madrid Summit ends with far-reaching decisions to transform NATO”. NATO. 30 June 2022.

- ^ Wolska, Anna (15 July 2023). “Fake of the week: Russia is waging war against NATO in Ukraine”. EURACTIV.pl.

- ^ “”Special military operation”, “Nazis” and “at war with NATO”: Russian state media framing of the Ukraine war”. ISPI. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Vavra, Shannon (21 September 2022). “‘The Time Has Come’: Top Putin Official Admits Ugly Truth About War”. The Daily Beast. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Tisdall, Simon (5 March 2023). “Nato faces an all-out fight with Putin. It must stop pulling its punches”. The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Sarotte, Mary Elise (2014). “A Broken Promise? What the West Really Told Moscow About NATO Expansion”. Foreign Affairs. 93 (5): 90–97. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 24483307.

- ^ Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: Scholarly debates, policy implications, and roads not taken Evaluating NATO Enlargement: From Cold War Victory to the Russia-Ukraine War: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 1-42 doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7_1.

- ^ Zollmann, Florian (30 December 2023). “A war foretold: How Western mainstream news media omitted NATO eastward expansion as a contributing factor to Russia’s 2022 invasion of the Ukraine”. Media, War & Conflict. 17 (3): 373–392. doi:10.1177/17506352231216908. ISSN 1750-6352. This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Korshunov, Maxim (16 October 2014). “Mikhail Gorbachev: I am against all walls”. rbth.com. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: From cold war victory to the Russia-Ukraine war: Springer International Publishing; 2023. 1-645 p doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7.

- ^ “Old adversaries become new partners”. NATO.

- ^ Iulian, Raluca Iulia (23 August 2017). “A Quarter Century of Nato-Russia Relations”. Cbu International Conference Proceedings. 5: 633–638. doi:10.12955/cbup.v5.998. ISSN 1805-9961.

- ^ “First NATO Secretary General in Russia”. NATO.

- ^ “Memorandum of Telephone Conversation, Bush-Yeltsin, December 8, 1991 | National Security Archive”. nsarchive.gwu.edu.

- ^ https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/?pdf=CDL(1994)054-e

- ^ https://cis.minsk.by/reestrv2/doc/1#text

- ^ “СССР прекратил существование, 11 республик вступают в СНГ”.

- ^ https://cis.minsk.by/reestrv2/doc/79#documentCard

- ^ “NATO’s Relations With Russia”. NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Belgium. 6 April 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ “NATO Strategic Concept for the Defence and Security of the Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization” (PDF). NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Belgium. 20 November 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ “The NATO-Russia Archive – Formal NATO-Russia Relations”. Berlin Information-Center For Translantic Security (BITS), Germany. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ “NATO PfP Signatures by Date”. NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Belgium. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/30920-document-8-cable-us-embassy-moscow-state-department-presidents-dinner-president

- ^ https://www.bfm.ru/news/542897

- ^ https://www.rbc.ru/politics/26/01/2024/65b31bcc9a7947b8bad62e39

- ^ https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/90894

- ^ Kozyrev, Andrei (2019). “Russia and NATO Enlargement: An Insider’s Account” (PDF).

- ^ Whitney, Craig R. (9 November 1995). “Russia Agrees To Put Troops Under U.S., Not NATO”. New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015.

- ^ Jones, James L. (3 July 2003). “Peacekeeping: Achievements and Next Steps”. NATO.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Lessons and Conclusions on the Execution of IFOR Operations and Prospects for a Future Combined Security System: The Peace and Stability of Europe after IFOR” (PDF). Foreign Military Studies Office. November 2000. p. 4.

- ^ Shevtsov, Leonty (21 June 1997). “Russian Participation in Bosnia-Herzegovina”.

- ^ Joulwan, George (21 June 1997). “The New NATO: The Way Ahead”.

I firmly believe that our cooperation at SHAPE and in Bosnia was instrumental in the creation of the NATO-Russia Founding Act, which was signed in May 1997 in Paris. As NATO’s Deputy Secretary General said, ‘Political reality is finally catching up with the progress you at SHAPE had already made.’

- ^ https://cis.minsk.by/reestrv2/print/documentCard?ids=6

- ^ https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/document/32237-document-14-memorandum-conversation-clinton-yeltsin-summit-helsinki-finland-subject

- ^ https://www.rbc.ru/politics/10/07/2024/668e862a9a7947761cca152b

- ^ Ronald D. Azmus, Opening NATO’s Door (2002) p. 210.

- ^ Strobe Talbott, The Russia Hand: A Memoir of Presidential Diplomacy (2002) p. 246.

- ^ Fergus Carr and Paul Flenley, “NATO and the Russian Federation in the new Europe: the Founding Act on Mutual Relations.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 15.2 (1999): 88–110.

- ^ “5/15/97 Fact Sheet: NATO-Russia Founding Act”. 1997-2001.state.gov. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “NATO Publications”. www.nato.int. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ “Nato-Russia Council – Documents & Glossaries”. www.nato.int. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ The NATO-Russia Joint Editorial Working Group (8 June 2021). “NATO-Russia Glossary of Contemporary Political and Military Terms” (PDF).

- ^ “Yeltsin: Russia will not use force against Nato”. The Guardian. 25 March 1999.

- ^ “Yeltsin warns of possible world war over Kosovo”. CNN. 9 April 1999.

- ^ Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: From cold war victory to the Russia-Ukraine war: Springer International Publishing; 2023. 1-645 p doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7. p.165.

- ^ “Russia Condemns NATO’s Airstrikes”. Associated Press. 8 June 1999.

- ^ Jackson, Mike (2007). Soldier. Transworld Publishers. pp. 216–254. ISBN 9780593059074.

- ^ “Confrontation over Pristina airport”. BBC News. 9 March 2000.

- ^ Peck, Tom (15 November 2010). “Singer James Blunt ‘prevented World War 3′”. Belfast Telegraph.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20001208050400/http://news2.thls.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/world/europe/newsid_666000/666501.stm

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20001208051500/http://news2.thls.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/world/europe/newsid_666000/666768.stm

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20041126012223/http://www.bbc.co.uk/russian/0305_1.shtml

- ^ https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/142046

- ^ Hall, Todd (September 2012). “Sympathetic States: Explaining the Russian and Chinese Responses September 11”. Political Science Quarterly. 127 (3): 369–400. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2012.tb00731.x.

- ^ “NATO–Russia Council Statement 28 May 2002” (PDF). NATO. 28 May 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Nato-Russia Council – About”. www.nato.int. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ NATO. “NATO – Official text: Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation signed in Paris, France, 27-May.-1997”. NATO. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Cook, Lorne (25 May 2017). “NATO: The World’s Largest Military Alliance Explained”. www.MilitaryTimes.com. The Associated Press, US. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ “Structure of the NATO-Russia Council” (PDF). Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ “Nato Blog | Dating Council”. www.nato-russia-council.info. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009.

- ^ “Nat-o Blog | Dating Council”. www.nato-russia-council.info.

- ^ “Nato Blog | Dating Council”. www.nato-russia-council.info. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009.

- ^ “Allies and Russia attend U.S. Nuclear Weapons Accident Exercise”. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ “NATO Summit Meetings – Rome, Italy – 28 May 2002”. www.nato.int. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ Ukraine News The Chronicles of War (24 June 2022). путин о вступлении Украины в НАТО. Retrieved 26 October 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Zwack, Peter B. (Spring 2004). “A NATO-Russia Contingency Command”. Parameters: 89.

- ^ Guinness World Records: First murder by radiation:

On 23 November 2006, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Litvinenko, a retired member of the Russian security services (FSB), died from radiation poisoning in London, UK, becoming the first known victim of lethal Polonium 210-induced acute radiation syndrome. - ^ “CPS names second suspect in Alexander Litvinenko poisoning”. The Telegraph. 29 February 2012. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Chapter 2. Rights and Freedoms of Man And Citizen | The Constitution of the Russian Federation. Constitution.ru. Retrieved on 12 August 2013.

- ^ “Russia warns of resorting to ‘force’ over Kosovo”. France 24. 22 February 2008.

- ^ In quotes: Kosovo reaction, BBC News Online, 17 February 2008.

- ^ “Putin calls Kosovo independence ‘terrible precedent'”. The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 February 2008.

- ^ “NATO’s relations with Russia”.

- ^ “Ukraine: NATO’s original sin”. Politico. 23 November 2021.

- ^ Menon, Rajan (10 February 2022). “The Strategic Blunder That Led to Today’s Conflict in Ukraine”. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ Bush backs Ukraine on Nato bid, BBC News (1 April 2008)

- ^ Ukraine Says ‘No’ to NATO, Pew Research Center (29 March 2010)

- ^ “Medvedev warns on Nato expansion”. BBC News. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ “Bush stirs controversy over NATO membership”. CNN. 1 April 2008.

- ^ “NATO Press Release (2008)108 – 27 Aug 2008”. Nato.int. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ “NATO Press Release (2008)107 – 26 Aug 2008”. Nato.int. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Pop, Valentina (1 April 2009). “Russia does not rule out future NATO membership”. EUobserver. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ “Nato-Russia relations plummet amid spying, Georgia rows”. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ “Военные считают ПРО в Европе прямой угрозой России – Мир – Правда.Ру”. Pravda.ru. 22 August 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Q&A: US missile defence”. BBC News. 20 September 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ NATO chief asks for Russian help in Afghanistan Reuters Retrieved on 9 March 2010

- ^ Angela Stent, The Limits of Partnership: U.S.-Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century (2014) pp 230–232.

- ^ “Medvedev: August War Stopped Georgia’s NATO Membership”. Civil Georgia. 21 November 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ “Russian and Nato jets to hold first ever joint exercise”. Telegraph. 1 June 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ “Nato rejects Russian claims of Libya mission creep”. The Guardian. 15 April 2011.

- ^ “West in “medieval crusade” on Gaddafi: Putin Archived 23 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine.” The Times (Reuters). 21 March 2011.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (21 April 2012). “Russians Protest Plan for NATO Site in Ulyanovsk”. The New York Times.

- ^ “NATO warns Russia to cease and desist in Ukraine”. Euronews.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ “Ukraine Crisis: NATO Suspends Russia Co-operation”. BBC News, UK. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Statement by NATO Foreign Ministers – 1 April 2014”. NATO.

- ^ “Address by President of the Russian Federation”. President of Russia.

- ^ “Why the Kosovo “precedent” does not justify Russia’s annexation of Crimea”. Washington Post.

- ^ Lars Molteberg Glomnes (25 March 2014). “Stoltenberg med hard Russland-kritikk” [Stoltenberg was met with fierce criticism from Russia]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 March 2014.

- ^ “Stoltenberg: – Russlands annektering er en brutal påminnelse om Natos viktighet” [Stoltenberg: – Russia’s annexation is a brutal reminder of the importance of NATO]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 28 March 2014. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014.

- ^ Tron Strand, Anders Haga; Kjersti Kvile, Lars Kvamme (28 March 2014). “Stoltenberg frykter russiske raketter” [Stoltenberg fears of Russian missiles]. Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 31 March 2014.

- ^ “NATO-Russia Relations: The Background” (PDF). NATO. March 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Joint Statement of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, 4 September 2014.

- ^ Joint statement of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, 2 December 2014.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (9 November 2014). “Close military encounters between Russia and the west ‘at cold war levels'”. The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ “Russia Baltic military actions ‘unprecedented’ – Poland”. UK: BBC News. 28 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ “Four RAF Typhoon jets head for Lithuania deployment”. UK: BBC News. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ “U.S. asks Vietnam to stop helping Russian bomber flights”. Reuters. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ “Russian Strategic Bombers To Continue Patrolling Missions”. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Schwartz, Paul N. (16 October 2014). “Russian INF Treaty Violations: Assessment and Response”. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gordon, Michael R. (28 July 2014). “U.S. Says Russia Tested Cruise Missile, Violating Treaty”. The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ “US and Russia in danger of returning to era of nuclear rivalry”. The Guardian. UK. 4 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R. (5 June 2015). “U.S. Says Russia Failed to Correct Violation of Landmark 1987 Arms Control Deal”. The New York Times. US. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Bodner, Matthew (3 October 2014). “Russia Overtakes U.S. in Nuclear Warhead Deployment”. The Moscow Times. Moscow. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ The Trillion Dollar Nuclear Triad Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies: Monterey, CA. January 2014.

- ^ Broad, William J.; Sanger, David E. (21 September 2014). “U.S. Ramping Up Major Renewal in Nuclear Arms”. The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ “Russian military attack on the Czech territory: details, implications and next steps” (PDF). Kremlin Watch Report. 21 April 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2021. Alt URL

- ^ Kramář, Rudolf (14 October 2020). “Zásah ve Vrběticích je po dlouhých letech ukončen” [The intervention in Vrbětice is over after many years]. hzscr.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ^ “Czechia expels Russian diplomats over 2014 ammunition depot blast”. Al Jazeera English. 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Eckel, Mike; Bedrov, Ivan; Komarova, Olha (18 April 2021). “A Czech Explosion, Russian Agents, A Bulgarian Arms Dealer: The Recipe For A Major Spy Scandal In Central Europe”. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Pavel, Petr (29 April 2024). “Czech president April 29th 2024 tweet on the 2014 ammunition depot explosion”.

- ^ Statement of Foreign Ministers on the Readiness Action Plan NATO, 02 Dec 2014.

- ^ “NATO condemns Russia, supports Ukraine, agrees to rapid-reaction force”. New Europe. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ “Nato shows its sharp end in Polish war games”. Financial Times. UK. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ “Nato testing new rapid reaction force for first time”. UK: BBC News. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ “Russia’s New Military Doctrine Hypes NATO Threat”. 30 December 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Putin signs new military doctrine naming NATO as Russia’s top military threat National Post, December 26, 2014.

- ^ “NATO Head Says Russian Anti-Terror Cooperation Important“. Bloomberg. 8 January 2015

- ^ “Insight – Russia’s nuclear strategy raises concerns in NATO”. Reuters. 4 February 2015. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Croft, Adrian (6 February 2015). “Supplying weapons to Ukraine would escalate conflict: Fallon”. Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Press Association (19 February 2015). “Russia a threat to Baltic states after Ukraine conflict, warns Michael Fallon”. The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ А.Ю.Мазура (10 March 2015). “Заявление руководителя Делегации Российской Федерации на переговорах в Вене по вопросам военной безопасности и контроля над вооружениями”. RF Foreign Ministry website.

- ^ Grove, Thomas (10 March 2015). “Russia says halts activity in European security treaty group”. Reuters. UK. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Aksenov, Pavel (24 July 2015). “Why would Russia deploy bombers in Crimea?”. London: BBC. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ “From Russia with Menace”. The Times. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (1 April 2015). “Norway Reverts to Cold War Mode as Russian Air Patrols Spike”. The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ New York Times: How a Poisoning in Bulgaria Exposed Russian Assassins in Europe

- ^ Euractiv: Bulgaria seeks extradition of three spies from Russia in Novichok case

- ^ Financial Times: Russian hitmen and saboteurs target Bulgaria’s arms industry, magnate says

- ^ Jump up to:a b MacFarquhar, Neil, “As Vladimir Putin Talks More Missiles and Might, Cost Tells Another Story”, New York Times, June 16, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ Not a single Russia-NATO cooperation program works — Russian diplomat TASS, 16 June 2015.

- ^ “US announces new tank and artillery deployment in Europe”. UK: BBC. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ “NATO shifts strategy in Europe to deal with Russia threat”. UK: FT. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Putin says Russia beefing up nuclear arsenal, NATO denounces ‘saber-rattling'”. Reuters. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Комментарий Департамента информации и печати МИД России по итогам встречи министров обороны стран-членов НАТО the RF Foreign Ministry, 26 June 2015.

- ^ Steven Pifer, Fiona Hill. “Putin’s Risky Game of Chicken”, New York Times, June 15, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ Steven Pifer. Putin’s nuclear saber-rattling: What is he compensating for? 17 June 2015.

- ^ “Russian Program to Build World’s Biggest Intercontinental Missile Delayed”. The Moscow Times. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ telegraph.co.uk: “US confirms it will place 250 tanks in eastern Europe to counter Russian threat”, 23 Jun 2015

- ^ telegraph.co.uk: “Nato updates Cold War playbook as Putin vows to build nuclear stockpile”, 25 Jun 2015

- ^ “NATO ‘very concerned’ by Russian military build-up in Crimea”. Hurriyet Daily News. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ “NATO-Russia Tensions Rise After Turkey Downs Jet”. The New York Times. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ “Turkey’s downing of Russian warplane – what we know”. BBC. 24 November 2015.

- ^ “ATO Invites Montenegro to Join, as Russia Plots Response”