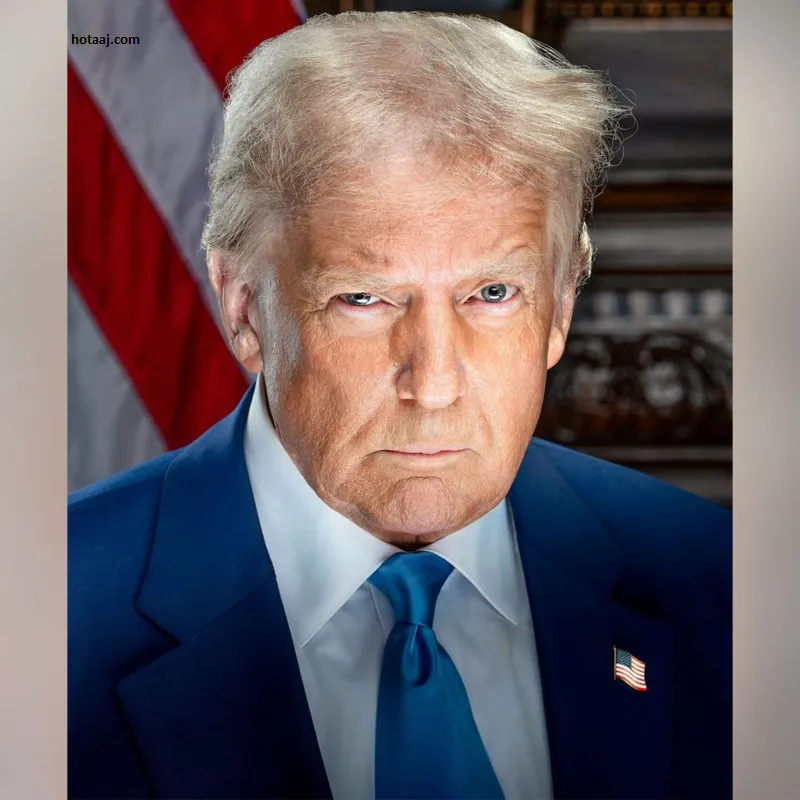

The official portraits of US President-elect Donald Trump and his vice president, JD Vance, have been released just days ahead of their inauguration, scheduled for Monday. The portraits show both men dressed in formal blue suits, white collared shirts, and matching blue ties. Trump’s image features him with a small US flag pin on his lapel, symbolizing his leadership and patriotism.

Trump’s expression in the portrait is serious and focused. His head is tilted slightly downward, with one eyebrow raised and his lips pressed together, giving him a determined, contemplative look. In contrast, Vance’s portrait presents a more relaxed vibe. The vice president-elect is smiling warmly at the camera, his arms crossed, exuding a sense of confidence and ease.

The release of these portraits comes as the nation prepares for a historic transition of power, marking the beginning of a new administration. With Trump and Vance both taking center stage, their official portraits offer a glimpse into their personalities, setting the tone for their leadership in the coming years.

The newly released official portrait of President-elect Donald Trump has drawn comparisons to his infamous 2023 mugshot, taken at Fulton County Jail after he was charged with attempting to overturn his 2020 election loss in Georgia — a charge he has denied. The mugshot, which became widely circulated, was later used by Trump to raise funds for his political campaign, further cementing its place in the public’s memory.

In the official portrait, Trump’s serious expression, with his head slightly tilted downward and his brow furrowed, has led many to draw parallels with the mugshot, adding another layer of intrigue to the image. Meanwhile, Vice President-elect JD Vance’s relaxed, smiling pose in his portrait contrasts with Trump’s more intense look.

In a press release accompanying the unveiling of the portraits, the Trump-Vance transition team described them as “going hard,” reflecting the team’s confident and bold approach as they prepare to take office. The phrase hints at the powerful statement both portraits aim to make as the new administration gears up for the challenges ahead.

The official portrait of President-elect Donald Trump, released ahead of his upcoming inauguration, stands in stark contrast to the one he used when he first became president in 2017. While both portraits feature similar attire — blue suits, white collared shirts, and blue ties — the earlier image showed Trump smiling broadly at the camera, embodying a more traditional and approachable presidential persona.

In contrast, the new portrait presents a more serious and determined version of Trump, with his head tilted slightly downward and a focused expression, possibly signaling a shift in how he wishes to be perceived. According to Quardricos Driskell, a political science professor at George Washington University, the new image could reflect Trump’s embrace of a “defiant” stance, transforming a moment of legal adversity into a symbol of “resilience and strength.”

Driskell also suggests that the stark difference between this portrait and his earlier, more traditional one could symbolize a shift in Trump’s public persona. “It could signify a tougher, more combative stance as he prepares to assume office for a second time,” Driskell told the BBC. The image could be seen as signaling Trump’s readiness to take on the challenges ahead with a more confrontational approach, both in politics and public perception.

The official portraits of President-elect Donald Trump and Vice President-elect JD Vance were released by the Trump transition team just days before their inauguration on January 20. This quick release contrasts with the previous administration, as the official portraits of Trump’s former Vice President Mike Pence and himself were not made public until nine months after they were both sworn in.

The portraits, which offer a snapshot of the leadership duo as they prepare for their upcoming term, reflect a confident and assertive image of the incoming administration. Trump’s serious, focused expression in his new portrait and Vance’s more relaxed pose provide a visual representation of the dynamic they hope to project in office.

Courtesy: LiveNOW from FOX

References

- ^ “World Development Indicators: Rural environment and land use”. World Development Indicators, The World Bank. World Bank. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “World Population Prospects 2022”. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100” (XSLX) (“Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)”). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Report for Selected Countries and Subjects”.

- ^ Dressing, David. “Latin America”. Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture. v. 5, 390

- ^ Bethell, Leslie (August 1, 2010). “Brazil and ‘Latin America'”. Journal of Latin American Studies. 42 (3): 457–485. doi:10.1017/S0022216X1000088X. ISSN 1469-767X.

- ^ Gistory (September 17, 2015). “Is Brazil Part of Latin America? It’s Not an Easy Question”. Medium. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ^ “Latin America” definition Archived September 22, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed May 20, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bilbao, Francisco (June 22, 1856). “Iniciativa de la América. Idea de un Congreso Federal de las Repúblicas” (in Spanish). París. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017 – via Proyecto Filosofía en español.

- ^ Britton, John A. (2013). Cables, Crises, and the Press: The Geopolitics of the New Information System in the Americas, 1866–1903. UNM Press. pp. 16–18. ISBN 9780826353986.

- ^ Mignolo, Walter (2005). The Idea of Latin America. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 77–80. ISBN 978-1-4051-0086-1.

- ^ Ardao, Arturo (1980). Genesis de la idea y el nombre de América Latina (PDF). Caracas, Venezuela: Centro de Estudios Latinoamericanos Rómulo Gallegos. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2019.

- ^ Rojas Mix, Miguel (1986). “Bilbao y el hallazgo de América latina: Unión continental, socialista y libertaria…”. Caravelle. Cahiers du monde hispanique et luso-brésilien. 46 (1): 35–47. doi:10.3406/carav.1986.2261. ISSN 0008-0152.

- ^ Gobat, Michel (December 1, 2013). “The Invention of Latin America: A Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism, Democracy, and Race”. The American Historical Review. 118 (5): 1345–1375. doi:10.1093/ahr/118.5.1345. ISSN 0002-8762. S2CID 163918139.

- ^ Edward, Shawcross (February 6, 2018). France, Mexico and informal empire in Latin America, 1820–1867 : equilibrium in the New World. Cham, Switzerland. p. 120. ISBN 9783319704647. OCLC 1022266228.

- ^ Gutierrez, Ramon A. (2016). “What’s in a Name?”. In Gutierrez, Ramon A.; Almaguer, Tomas (eds.). The New Latino Studies Reader: A Twenty-First-Century Perspective. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-520-28484-5. OCLC 1043876740.

The word latinoamericano emerged in the years following the wars of independence in Spain’s former colonies […] By the late 1850s, californios were writing in newspapers about their membership in América latina (Latin America) and latinoamerica, calling themselves Latinos as the shortened name for their hemispheric membership in la raza latina (the Latin race). Reprinting an 1858 opinion piece by a correspondent in Havana on race relations in the Americas, El Clamor Publico of Los Angeles surmised that ‘two rival races are competing with each other … the Anglo Saxon and the Latin one [la raza latina].’

- ^ “América latina o Sudamérica?, por Luiz Alberto Moniz Bandeira, Clarín, 16 de mayo de 2005″. Clarin.com. May 16, 2005. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ José María Torres Caicedo (September 26, 1856). “Las dos Américas” (in Spanish). Venice. Archived from the original on July 22, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2013 – via Proyecto Filosofía en español.

- ^ Bilbao, Francisco. “Emancipación del espíritu de América”. Francisco Bilbao Barquín, 1823–1865, Chile. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ RAE (2005). Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas. Madrid: Santillana Educación. ISBN 8429406239. Archived from the original on April 4, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

- ^ Rangel, Carlos (1977). The Latin Americans: Their Love-Hate Relationship with the United States. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-15-148795-0. Skidmore, Thomas E.; Peter H. Smith (2005). Modern Latin America (6th ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-0-19-517013-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Torres, George (2013). Encyclopedia of Latin American Popular Music. ABC-CLIO. p. xvii. ISBN 9780313087943.

- ^ Butland, Gilbert J. (1960). Latin America: A Regional Geography. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 115–188. ISBN 978-0-470-12658-5.

Dozer, Donald Marquand (1962). Latin America: An Interpretive History. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1–15. ISBN 0-87918-049-8.

Szulc, Tad (1965). Latin America. New York Times Company. pp. 13–17. ISBN 0-689-10266-6.

Olien, Michael D. (1973). Latin Americans: Contemporary Peoples and Their Cultural Traditions. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-03-086251-9.

Black, Jan Knippers, ed. (1984). Latin America: Its Problems and Its Promise: A Multidisciplinary Introduction. Boulder: Westview Press. pp. 362–378. ISBN 978-0-86531-213-5.

Burns, E. Bradford (1986). Latin America: A Concise Interpretive History (4th ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall. pp. 224–227. ISBN 978-0-13-524356-5.

Skidmore, Thomas E.; Peter H. Smith (2005). Modern Latin America (6th ed.). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 351–355. ISBN 978-0-19-517013-9. - ^ Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings Archived April 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, UN Statistics Division. Accessed on line May 23, 2009. (French Archived December 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Latin America and the Caribbean Archived May 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The World Bank. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ “Country Directory. Latin American Network Information Center-University of Texas at Austin”. Lanic.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo, Latin America: The Allure and Power of an Idea. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2017, 1, 3.

- ^ Francisco Bilbao, La América en peligro, Buenos Aires: Impr. de Berheim y Boeno 1862, 14, 23, quoted in Tenorio-Trillo, Latin America, p. 5.

- ^ Gongóra, Alvaro; de la Taille, Alexandrine; Vial, Gonzalo. Jaime Eyzaguirre en su tiempo (in Spanish). Zig-Zag. p. 223.

- ^ “South America, Latin America”. Reflexions. University of Liège. Archived from the original on November 24, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2022.

- ^ “Language and education in Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao”. ResearchGate. Archived from the original on September 25, 2024. Retrieved December 16, 2024.

- ^ María Alejandra Acosta Garcia; González, Sheridan; Ma. de Lourdes Romero; Reza, Luis; Salinas, Araceli (June 2011). “Three”. Geografía, Quinto Grado [Geography, Fifth Grade] (Second ed.). Mexico City: Secretaría de Educación Pública [Secretariat of Public Education]. pp. 75–83 – via Comisión Nacional de Libros de Texto Gratuitos (CONALITEG).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Central Intelligence Agency (2023). “The World Factbook – Country Comparisons: Population”. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “United Nations Statistics Division – Demographic and Social Statistics”. unstats.un.org. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Téléchargement du fichier d’ensemble des populations légales en 2017 Archived October 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, INSEE

- ^ Ospina, Jose (October 28, 2018). “Is there a right-wing surge in South America?”. DW. Archived from the original on December 31, 2022. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ “Conservative Lacalle Pou wins Uruguay presidential election, ending 15 years of leftist rule”. France 24. November 29, 2019. Archived from the original on June 13, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ Jordi Zamora. “China’s double-edged trade with Latin America”. September 3, 2011. AFP.

- ^ Casey, Nicholas; Zarate, Andrea (February 13, 2017). “Corruption Scandals With Brazilian Roots Cascade Across Latin America”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ Andreoni, Manuela; Londoño, Ernesto; Darlington, Shasta (April 7, 2018). “Ex-President ‘Lula’ of Brazil Surrenders to Serve 12-Year Jail Term”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ “Another former Peruvian president is sent to jail, this time as part of growing corruption scandal”. Los Angeles Times. July 14, 2017. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Weiffen, Brigitte (December 1, 2020). “Latin America and COVID-19: Political Rights and Presidential Leadership to the Test”. Democratic Theory. 7 (2): 61–68. doi:10.3167/dt.2020.070208. ISSN 2332-8894. Archived from the original on January 21, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good? (PDF). UNESCO. 2015. pp. 24, Box 1. ISBN 978-92-3-100088-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 13, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Report on World Social Situation 2013: Inequality Matters. United Nations. 2013. ISBN 978-92-1-130322-3. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ^ Protección social inclusiva en América Latina. Una mirada integral, un enfoque de derechos [Inclusive social protection in Latin America. An integral look, a focus on rights]. United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (UNECLAC). March 2011. ISBN 9789210545556. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ Nutini, Hugo; Isaac, Barry (2009). Social Stratification in central Mexico 1500–2000. University of Texas Press. p. 55.

There are basically four operational categories that may be termed ethnic or even racial in Mexico today: (1) güero or blanco (white), denoting European and Near East extraction; (2) criollo (creole), meaning light mestizo in this context but actually of varying complexion; (3) mestizo, an imprecise category that includes many phenotypic variations; and (4) indio, also an imprecise category. These are nominal categories, and neither güero/blanco nor criollo is a widely used term (see Nutini 1997: 230). Nevertheless, there is a popular consensus in Mexico today that these four categories represent major sectors of the nation and that they can be arranged into a rough hierarchy: whites and creoles at the top, a vast population of mestizos in the middle, and Indians (perceived as both a racial and an ethnic component) at the bottom.

- ^ Seed, Patricia (1988). To Love, Honor, and Obey in Colonial Mexico: conflicts over Marriage Choice, 1574–1821. Stanford: Stanford University. pp. 21–23. ISBN 0-8047-2159-9.

- ^ Francisco H. Ferreira et al. Inequality in Latin America: Breaking with History?, The World Bank, Washington, D.C., 2004

- ^ Jones, Nicola; Baker, Hayley. “Untangling links between trade, poverty and gender”. ODI Briefing Papers 38, March 2008. Overseas Development Institute (ODI). Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Baten, Jörg; Mumme, Christina (2010). “Globalization and educational inequality during the 18th to 20th centuries: Latin America in global comparison”. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History. 28 (2): 279–305. doi:10.1017/S021261091000008X. hdl:10016/21558. S2CID 51961447.

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 148f. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ Nations, United. “UNDP HDI 2020”. UNDP. Archived from the original on November 2, 2010. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ “GDP per Capita Ranking 2015 – Data and Charts”. Knoema. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ “Human Development Report 2011” (PDF). Table 3: Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ “Human Development Report 2011” (PDF). Table 5: Multidimensional Poverty Index. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ “ADULT AND YOUTH LITERACY: National, regional and global trends, 1985-2015” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2016.

- ^ “Geoba.se: Gazetteer – The World – Life Expectancy – Top 100+ By Country (2016)”. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ “Homicide Statistics 2014”. Murder rate per 100,000 inhabitants. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Global Rankings”. Vision of Humanity. Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP). July 24, 2020. Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ “socio-economic policies” (PDF). dane.gov.co. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ “Statistic yearbook” (PDF). policica.gob.ni. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ “Life expectancy at birth, total”. The World Bank Group. May 30, 2024. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ “Life expectancy at birth, male”. The World Bank Group. May 30, 2024. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ “Life expectancy at birth, female”. The World Bank Group. May 30, 2024. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ “Global Metro Monitor 2014”. Brookings Institution. January 22, 2015. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ Andrews, George Reid. 1980. The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires, 1800–1900, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press

- ^ Gilberto Freyre. The Masters and the Slaves: A Study in the Development of Brazilian Civilization. Samuel Putnam (trans.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Thomas E. Skidmore. Black into White: Race and Nationality in Brazilian Thought. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

- ^ France Winddance Twine Racism in a Racial Democracy: The Maintenance of White Supremacy in Brazil,(1997) Rutgers University Press

- ^ “Reference for Welsh language in southern Argentina, Welsh immigration to Patagonia”. Bbc.co.uk. July 22, 2008. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ “The Welsh Immigration to Argentina”. 1stclassargentina.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ “Reference for Welsh language in southern Argentina, Welsh immigration to Patagonia”. Andesceltig.com. September 29, 2009. Archived from the original on September 17, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ^ Meade, Teresa A. (2016). History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-118-77248-5.

- ^ “Christians”. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. December 18, 2012. Archived from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

- ^ “CIA – The World Factbook – Field Listing – Religions”. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ Fraser, Barbara J., In Latin America, Catholics down, church’s credibility up, poll says Archived June 28, 2005, at the Library of Congress Web Archives Catholic News Service June 23, 2005

- ^ “The Global Religious Landscape” (PDF). Pewforum.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 25, 2017. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ^ Alec Ryrie, “The World’s Local Religion” History Today (2017) online Archived September 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Religion in Latin America, Widespread Change in a Historically Catholic Region”. Pew Research Center. November 13, 2014. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ Burden, David K. La Idea Salvadora: Immigration and Colonization Politics in Mexico, 1821–1857. University of California, Santa Barbara, 2005.

- ^ Gutmann, Myron P., et al. “The demographic impact of the Mexican Revolution in the United States.” Austin: Population Research Center, University of Texas (2000)

- ^ Young, Julia G. “Cristero Diaspora: Mexican Immigrants, The US Catholic Church, and Mexico’s Cristero War, 1926–29.” The Catholic Historical Review (2012): 271–300.